Faultlines of freedom: The complex ties of Jinnah, Suhrawardy and Gandhi

Mohammad Ali Jinnah was the principal architect of Pakistan, while Shaheed Suhrawardy was one of the movement's firmest pillars. Both men were marked by courage and energy.

Suhrawardy's popularity, unlike Jinnah's, was rooted primarily in the regional sphere, though he enjoyed a strong base of mass support. Jinnah's emergence as the architect of Pakistan owed considerably to Suhrawardy's efforts, yet Suhrawardy, in turn, received comparatively little support from Jinnah.

Their ages were separated by sixteen years, and their political association, which began in August 1927, endured for almost two decades. In the aftermath of the All-India riots of 1926, a peace conference was convened in Simla with both Hindu and Muslim representatives. Jinnah and Suhrawardy were present on that occasion: Jinnah had not yet fully severed his ties with the Congress to join the League, while Suhrawardy had only just begun to take part in some of the League's programmes.

At that time, the growing hostility between Hindus and Muslims created in the minds of both Jinnah and Suhrawardy a sense that the prospect of Hindu-Muslim unity might forever remain elusive. The belief that both communities could drive out the British together and then jointly govern their homeland appeared to them as little more than a fable.

Behind Suhrawardy's disillusionment lay the failure of the 1923 "Bengal Pact." Similarly, Jinnah's frustration with Hindu-Muslim unity stemmed from the similar fate of the 1916 "Lucknow Pact."

Suhrawardy thereafter devoted increasing attention to organising his community in Bengal, while Jinnah sought to do so on the national stage—though not immediately. Jinnah spent nearly four years (from 1930) in self-imposed exile in London. After Jinnah's return to India in 1934, as he began searching for new organisers, an organisational partnership between the two men gradually emerged.

The closeness between Jinnah and Suhrawardy was shaped in 1936 through the influence of Hasan Ispahani and the Aga Khan. That same year, Suhrawardy was appointed general secretary of the Bengal Provincial Muslim League. Although Jinnah's clear preference lay with Nazimuddin and Ispahani, he recognised that if the League was to emerge as the dominant force in Bengal, Suhrawardy's involvement was indispensable. The alliance that followed enabled the League to stand firmly against Fazlul Huq's party.

Ispahani later recalled that when Jinnah first arrived in Calcutta in 1936 and stepped down at Howrah station, only three people were there to receive him. A decade later, in 1946, he returned to Bengal for the election campaign and was greeted by thousands. This remarkable transformation was the result of the organisational efforts of Suhrawardy and Abul Hashim.

It was Suhrawardy and Hashim who liberalised the League's membership rules and travelled through the villages, turning the organisation into a party of ordinary Muslims. The fruits of this strategy were fully realised in the 1946 elections. Yet the outcome was more than the League's victory over the Krishak Praja Party; it was also a personal triumph for Suhrawardy over Jinnah. Within Bengal, Jinnah's favoured faction, led by Khwaja Nazimuddin, was largely marginalised. At the same time, the League's sweeping victory in Bengal gave Jinnah formidable bargaining power at the all-India level—so much so that he could eventually sideline Suhrawardy himself.

Even as leading figures within the same party, Jinnah and Suhrawardy maintained a constant, if silent, rivalry. They never spoke against one another in public, yet the competition was unmistakable.

After the final collapse of Fazlul Huq's second government in 1943, Suhrawardy was the strongest contender within the League for the premiership of Bengal. Yet Jinnah's preference was firmly for Nazimuddin, as correspondence between Jinnah and Ispahani in April 1943 makes clear.

Jinnah also ensured that Suhrawardy's influence did not extend beyond Bengal. Yet in 1946, when Jinnah announced the "Direct Action Day" programme, it was Suhrawardy who took the lead in carrying it out.

Both men were committed to advancing Muslim interests in India, but their priorities differed. Jinnah's focus was on Muslims across the subcontinent, particularly in the north, while Suhrawardy's concern lay above all with the Muslims of Bengal.

Jinnah may have been the central leader, but Suhrawardy was not always willing to submit to his authority in Bengal. In organisational matters, he preferred to act independently. A clear example was the election of Abul Hashim as provincial secretary of the League. When Hashim, Suhrawardy's chosen secretary, sought to launch a weekly newspaper titled Millat, Jinnah showed little enthusiasm, favouring instead The Daily Azad of Maulana Akram Khan. Even during provincial elections, Jinnah tended to send financial assistance not to Suhrawardy but to Ispahani.

By the 1946 elections, tensions between these factions of the Bengal League had hardened, especially as victory seemed inevitable. With Nazimuddin defeated, Suhrawardy emerged dominant in the League's internal power struggle. Yet to secure Jinnah's consent as Chief Minister, he was obliged—at least tacitly—to accept the central League's vision of India's future as two separate states, meaning Bengal's Muslims would have to commit themselves to Jinnah's proposed Pakistan. Even so, Suhrawardy did not abandon his parallel efforts to preserve a united Bengal.

After Partition in 1947, Suhrawardy did not gain the position in East Pakistan he had anticipated. His faction lacked ideological cohesion and was held together mainly by his personal authority. With Jinnah and Liaquat Ali Khan backing Nazimuddin, Suhrawardy was marginalised with relative ease.

By early 1947, it became clear that Calcutta was witnessing a new Suhrawardy: one who, disillusioned with Jinnah, began to look instead towards Gandhi.

II

Suhrawardy's relationship with Gandhi is rarely discussed, yet it remains one of the most remarkable political chapters in Bengal's history.

In August 1947, the two men, despite risking the hostility of their political colleagues, stood together in Calcutta to stem the tide of communal violence. That same month, however, stripped them both of political power. Suhrawardy would in time recover; Gandhi was denied the chance, struck down by Hindu extremists.

Their close connection was forged in the aftermath of the Noakhali riots, when they exchanged frequent letters. The wounds of the Calcutta riots were still raw when violence erupted in Noakhali. For Suhrawardy, already under severe criticism for his handling of Calcutta, Noakhali proved an additional political disaster. Yet it also gave him an opportunity to rehabilitate his reputation through active engagement in relief and peace efforts. His success was limited. Most controversially, he defended Gholam Sarwar, a leading Muslim figure accused of instigating the violence, declaring him innocent in a statement published in the Star of India on 17 October, 1946. Critics also accused him of understating the death toll.

In the second month of the Noakhali riots, violence also broke out in Bihar, where Muslims were the main victims. With Calcutta, Noakhali and Bihar aflame, the crisis became both humanitarian and political. Suhrawardy's administration was further burdened with resettling in Calcutta those displaced from Bihar. For this reason, he did not accompany Gandhi on his Noakhali mission, though he visited the district twice during the unrest, both before and after Gandhi's stay.

To ensure Gandhi's journey to Noakhali passed without hindrance, Suhrawardy arranged a special train from Calcutta and dispatched his cabinet colleague, Labour Minister Shamsuddin Ahmed, to receive him. Suhrawardy himself travelled to Kajirkhil in Noakhali on 19 November 1946 to meet Gandhi, having earlier visited Feni with Governor Burrows on 18 October.

On 10 and 12 May 1947, Suhrawardy again sought Gandhi's support for a united Bengal. His appeals, however, came to nothing. Within Congress, decisions now rested with Nehru and Patel, while on the streets it was the riots that dictated events.

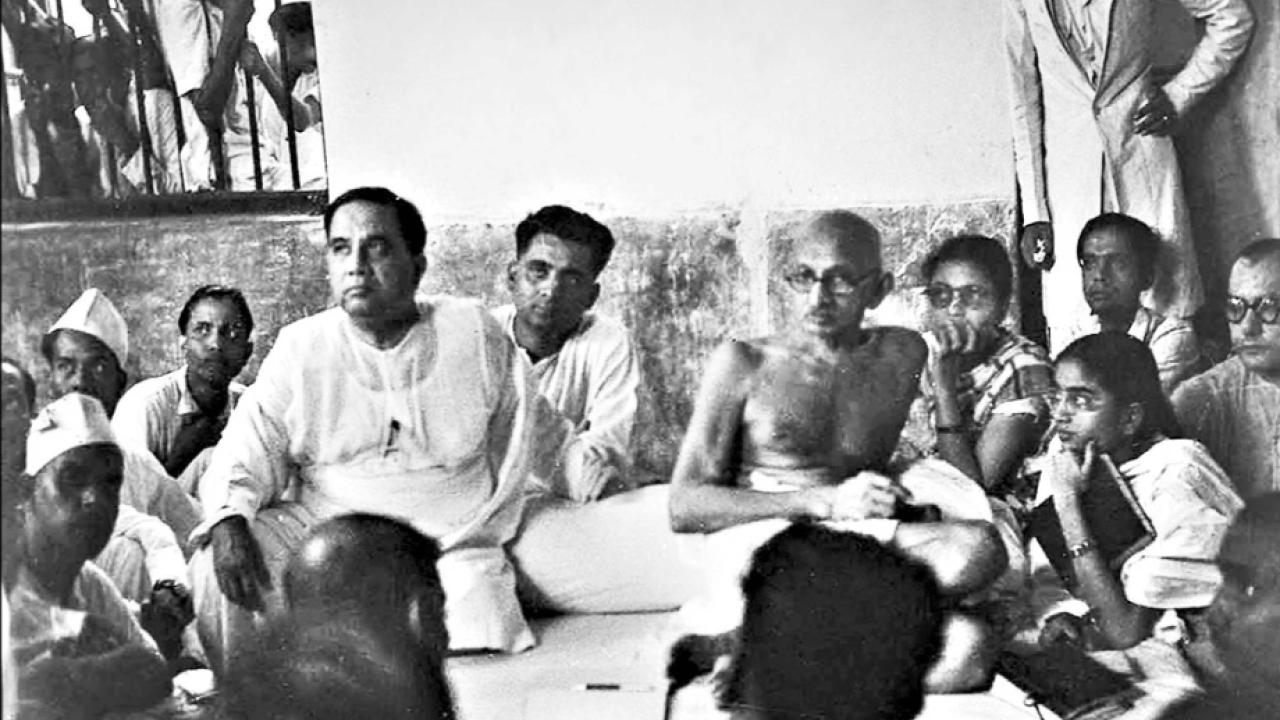

Yet in August 1947, in the final days of an undivided India, Gandhi and Suhrawardy together created in Calcutta a remarkable political episode unmatched in Bengal's later history.

After completing the first phase of his Noakhali peace mission, Gandhi had gone to Kashmir. On 1 August 1947, as he prepared to depart again for Noakhali, Suhrawardy and other Muslim leaders persuaded him to remain in Calcutta. Gandhi's decision to postpone his journey and stay was a bold one; for local Muslims, it brought reassurance.

He agreed on two conditions: that Suhrawardy remain by his side, and that as Chief Minister he take responsibility for the safety of Hindus in Noakhali. Suhrawardy accepted both, and requested in turn that Gandhi stay in a neighbourhood where Muslims had suffered most in the riots.

Thus they gathered at Hyderi Manzil, on Suresh Chandra Banerjee Road in Beliaghata—an abandoned Muslim house, today known as "Gandhi Bhavan." From 13 August, Gandhi lived there continuously, while Suhrawardy joined him part of each day.

The ruined house mirrored the condition of its occupants. Gandhi's principle of non-violence had lost much of its appeal in Bengal and India as a whole, while Suhrawardy's idea of a united Bengal had all but slipped into history. Yet their joint satyagraha at Hyderi Manzil had a strikingly positive effect on a volatile Calcutta.

Gandhi's decision to stay in Calcutta for Muslim interests, rather than return to Noakhali, angered many Hindus. Suhrawardy's own safety soon came under threat; on one occasion, a bomb was hurled at his car in Beliaghata.

On 4 September, thirty-five men appeared before the fasting Gandhi, confessing to killings they had committed during the riots and pledging to desist if he ended his fast. After this collective assurance, Gandhi broke his fast by drinking sherbet from Suhrawardy's hands. On 7 September, he left Calcutta for Delhi. Suhrawardy bade him farewell at the railway station, in a moment remembered for its poignancy—he wept openly.

Gandhi and Suhrawardy's association was defined by both similarities and differences — one deeply honourable, the other profoundly tragic.

Altaf Parvez is the author of Suhrawardy o Banglay Musalmaner Rashtrasadhana (Oitijjhya, 2024).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments