Hadron collider restarts after rebuild

The Large Hadron Collider has restarted, with protons circling the machine's 27km tunnel for the first time since 2013.

Particle beams have now travelled in both directions, inside parallel pipes, at a whisker below the speed of light.

Actual collisions will not begin for at least another month, but they will take place with nearly double the energy the LHC reached during its first run.

Scientists hope to glimpse a "new physics" beyond the Standard Model.

Rolf Heuer, the director-general of Cern, which operates the LHC, told engineers and scientists at the lab: "Congratulations. Thank you very much everyone… now the hard work starts".

Cern's director for accelerators and technology, Frédérick Bordry, said: "After two years of effort, the LHC is in great shape.

"But the most important step is still to come when we increase the energy of the beams to new record levels."

The beams have arrived a week or so later than originally scheduled, due to a now-resolved electrical fault.

The protons are injected at a relatively low energy to begin with. But over the coming months, engineers hope to gradually increase the beams' energy to 13 trillion electronvolts: double what it was during the LHC's first operating run.

After 08:30 GMT, engineers began threading the proton beam through each section of the enormous circle, one-by-one, before completing multiple full turns. It was later joined by the second beam, in parallel.

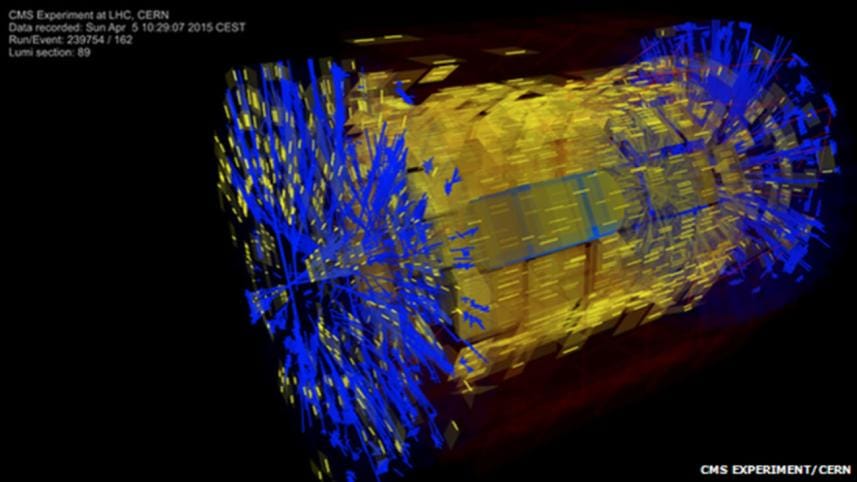

The experiment teams have already detected "splashes" of particles, which occur when stray protons hit one of the shutters used to keep the beam on-track. If this happens in part of the pipe near one of the experiments, the detectors can pick up some of the debris.

"It's fantastic to see it going so well after two years and such a major overhaul of the LHC," said Prof Heuer.

"I am delighted and so is everyone in the Cern control centre - as are, I'm sure, colleagues across the high-energy physics community."

Big unknowns

Physicists are frustrated by the existing Standard Model of particle physics. It describes 17 subatomic particles, including 12 building blocks of matter and 5 "force carriers" - the last of which, the Higgs boson, was finally detected by the LHC in 2012.

Prof Tara Shears, from the University of Liverpool, works on one of the LHC's four big experiments that will soon recommence their work, slamming protons together and quantifying the fallout.

"Of course in every particle physics experiment we've ever done, we've been wanting to make a big, unknown discovery," Prof Shears told BBC News.

"But now it's become particularly pressing, because with Run One and the discovery of the Higgs, we've discovered everything that our existing theory predicts."

In order to explain several baffling properties of the universe, things beyond the Standard Model have been proposed - but never directly detected.

These include dark energy, the all-pervading force suggested to account for the universe expanding faster and faster. And dark matter - the "web" that holds all visible matter in place, and would explain why galaxies spin much faster than they should, based on what we can see.

A theory called supersymmetry proposes additional particles, as yet unseen, that might fill in some of these gaps. But no experiment, including the LHC, has yet found evidence for anything "supersymmetrical".

Even the familiar and crucial force of gravity is nowhere in the Standard Model.

Waiting game

By taking matter to states we have never observed before - the LHC's collisions create temperatures not seen since moments after the Big Bang - physicists hope to find something unexpected that addresses some of these questions.

Debris from the tiny but history-making smash-ups might contain new particles, or tell-tale gaps betraying the presence of dark matter or even hidden dimensions.

But first we need collisions - due in May at the earliest - and then a steady torrent of data will make its way to physicists around the world, so that the massive analysis effort can begin.

Even when the results start to flow, we shouldn't hold our breath anticipating a breakthrough, according to Steven Goldfarb who works on the Atlas experiment.

Dr Goldfarb remembers working on Cern's previous atom smasher, the LEP collider, which commenced operations in 1989. Then, just like today, there was much excitement about staging higher-energy collisions than ever before.

"We thought at that time, perhaps we'd find the Higgs, perhaps we'd find supersymmetry. Many of the things we're looking for now, we looked for then," he told the BBC.

"In the end, we just measured the Standard Model more and more precisely. We put a lot of really good constraints on it, which taught us where to look for the Higgs - but there were no Eureka discoveries.

"And that could really be the case for the next several years."

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments