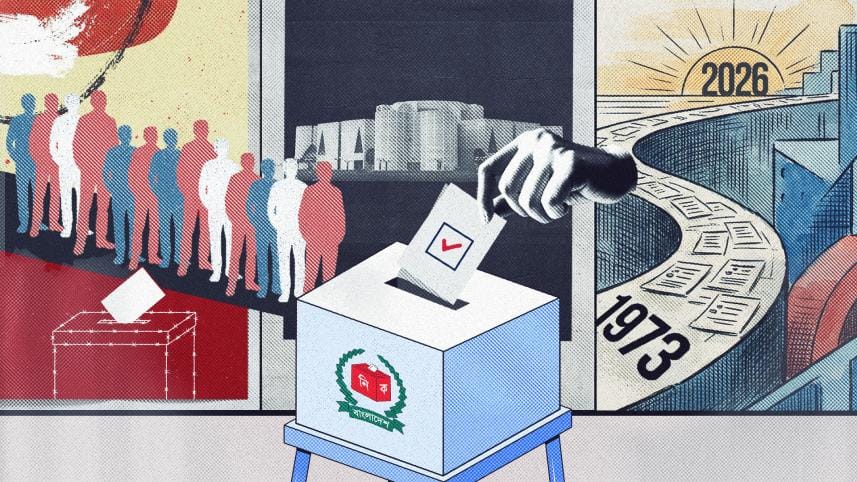

Facing the most vital election ever

After the last three manipulated elections, the people of Bangladesh are eagerly waiting to exercise their fundamental right to vote. Any deprivation of this right will not be acceptable, and those who are trying to scuttle it will be at the receiving end of public wrath, never to be forgiven.

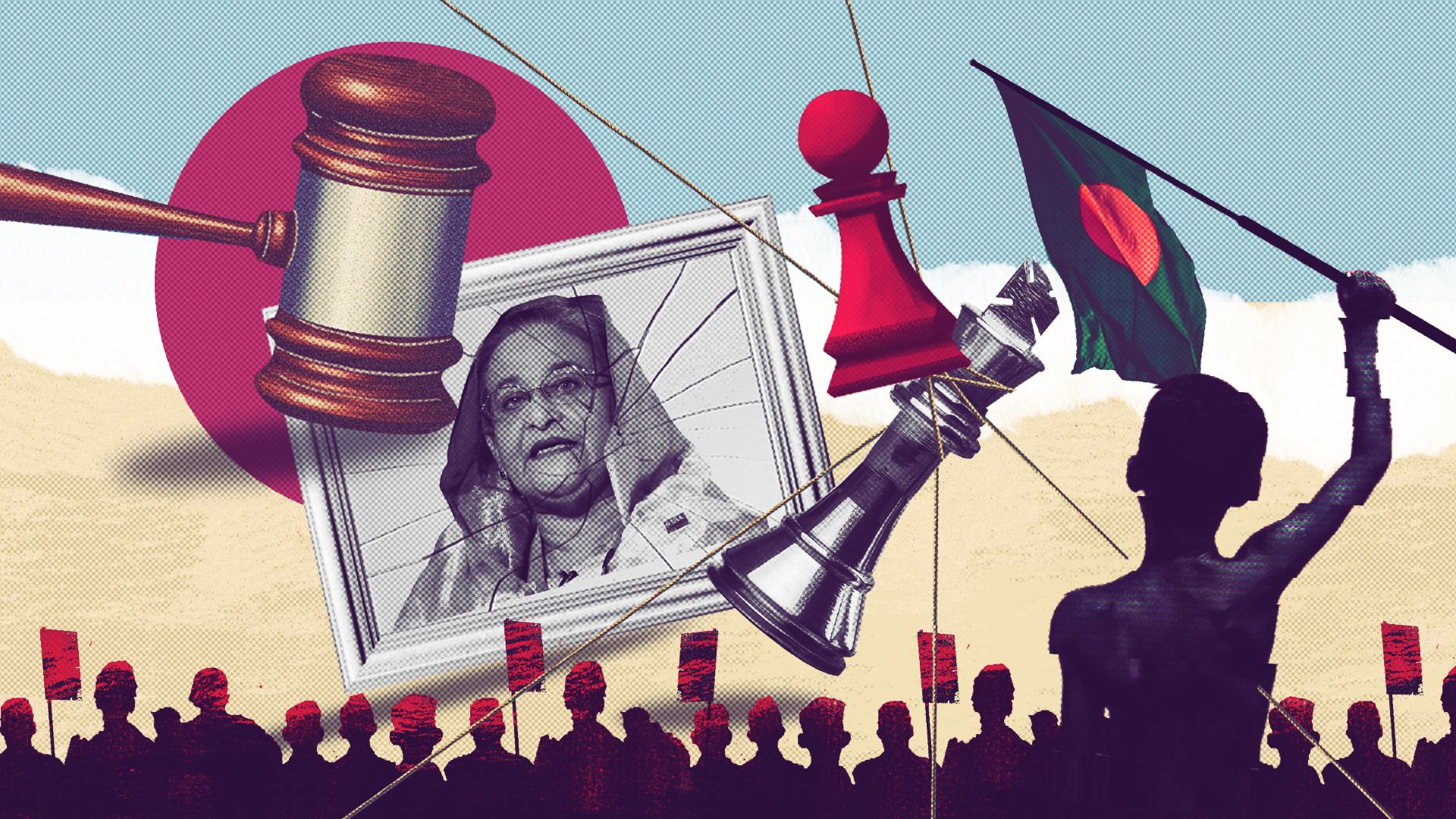

We are now heading towards the long-awaited poll that will, no doubt, reflect the people's choice. Though the absence of a major party—Awami League—will create its own debates, its failure to acknowledge and apologise for the crimes it committed, such as enforced disappearances, extrajudicial killings, the destruction of democratic institutions, and finally wanton killings during the 2024 July uprising, has left the party deeply distanced from the people.

To hold the election peacefully, we need to stabilise civic life to some extent. While we not only acknowledge but also support every group's right to protest, we cannot be oblivious to others' right to earn their daily bread, perform essential chores, attend offices, allow businesses to operate, banks to function, retail shop owners and poor hawkers to carry on earning their meagre incomes, and rickshaw pullers to provide food for their families—in short, allowing people to enjoy their basic rights and freedoms. The intention of protesters may not be to stop anything, but it often ends up doing exactly that. The paralysing traffic jams say it all.

Being a highly emotion-driven nation, we tend to forget that whatever we may do internally, we must adhere to a set of international norms and practices to be accepted as a credible player in the global system. For example, if we want to export garments, we must comply with certain labour, environmental and quality standards to attract international buyers. Similarly, if we want other countries to invest in Bangladesh, we need to guarantee a fair legal framework, a certain standard of safety and security in daily life, a dependable law-and-order situation, and a governance system that inspires confidence among investors so that they choose to invest here rather than elsewhere. Vietnam is a communist country, yet the entire capitalist world competes to invest there. Shouldn't we ask why?

As the election nears, we feel there is much to learn from the past. Why, after five decades, is our democracy still so weak? What were our past mistakes? Did we learn anything from them? If not, why not? And why do we still consider our political opponents as "enemies"?

As far as our memory serves, our parliament has largely functioned as a rubber stamp since 1973. Otherwise, how could we have transformed our constitution, betrayed the values of the Liberation War, and instituted BAKSAL? Later, even when the opposition had a large presence in the House, why did parliament fail to become the centre of transparency and to hold the executive branch accountable? Why didn't a single MP become a "conscientious objector" when enforced disappearances and extrajudicial killings became rampant? Too often, our MPs lacked the moral courage to serve voters and instead served merely as cogs in the party machinery.

As we prepare to hold the coming election with earnestness and hope, we need to reflect on why so many of our past elections have been controversial. We have held a total of 12 elections to date: in 1973, 1979, 1986, 1988, 1991, February 1996, June 1996, 2001, 2008, 2014, 2018 and 2024. Of these, only four—1991, June 1996, 2001, and 2008—are generally seen as credible, while the remaining eight are widely considered controversial.

A closer examination of our first election held in 1973 shows how we started on the wrong foot. With a voter turnout of 55 percent, Awami League (AL) won 293 out of 300 seats. There were many reasons for this overwhelming victory—Bangabandhu's presence, the 1970 election under Pakistan in which the AL won 160 of the 162 seats allocated to East Pakistan, the Liberation War, and the emergence of an independent Bangladesh. Yet, even amid such stupendous support, there was a fatal flaw in Bangabandhu's thinking: the lack of foresight to ensure that the first parliament of the new nation included some strong, independent and critical voices, not only for a nascent democracy but also for his own government's success. He should have made special efforts to bring into the fold of the first parliament seasoned politicians and young activists who were known to have had the courage to challenge even him. Even if such individuals lacked electoral strength, he should have devised ways and means to bring them into parliament and allow them the freedom to point out the shortcomings of the government.

Even outside parliament, only a few voices of dissent were left, including Abul Mansur Ahmad in The Daily Ittefaq, Enayetullah Khan in the weekly Holiday, poet Al-Mahmud of the daily Gonokantho and Abdus Salam, editor of the Bangladesh Observer.

Such absolute control of parliament got us started on a flawed course, the consequences of which proved fatal. It gave birth to a culture of intolerance, an incapacity to accept criticism, and a deep disdain for dissent. The overwhelming majority effectively turned our first elected legislature into a one-party parliament, sowing the seeds of BAKSAL that would become a nightmarish reality within a few years.

The anti-Ershad movement and his subsequent fall gave Bangladesh a chance to relaunch its journey towards democracy. The interim government under Justice Shahabuddin Ahmed conducted a superb election and generated public confidence in the caretaker system, which was further strengthened by the performances of Justice Muhammad Habibur Rahman in 1996 and Justice Latifur Rahman in 2001. Although the caretaker government of Fakhruddin Ahmed, backed by the then army chief General Moinuddin, faced controversies because of the way it was formed, the election it conducted under Chief Election Commissioner Shamsul Huda enjoyed a certain degree of credibility.

Tragically, after returning to power, Sheikh Hasina abolished the caretaker system, resulting in three disastrous elections that destroyed all institutions of accountability and undermined free and fair electoral processes.

With the current interim government overseeing the coming election and an Election Commission in place, the nation now looks forward to the restoration of the democratic process that was derailed over the 15 years of the AL rule. As we prepare to return to democratic rule, we must learn and act on the lessons necessary to ensure that our future democratic journey succeeds.

The first thing to remember is that in a parliamentary system, the roles of parties, elected MPs, and their relationship with the party leader and the government are quite delicate and well-delineated. Consider the UK example. Under Boris Johnson's leadership, the Conservative Party won handsomely in 2019. Yet he lost his party's confidence in 2022 and was replaced by Liz Truss as leader of the party, in which capacity she became prime minister in September 2022. In less than two months, she was replaced by Rishi Sunak as leader of the party, which made him the prime minister. Neither of these two prime ministers faced any election and yet they replaced someone whom the people voted for. This means that in a parliamentary form of government, it is the party that gets elected and anyone who is elected as party chief gets to head the government.

Although Bangladesh follows the same parliamentary system in theory, our practices are completely different. Our political tradition is not conducive to nurturing what we cited above. For us, the leaders run their parties with total control. In no way does the party determine what and how the leader will act. For us, the party is always leader-driven. Bangabandhu personified the AL, President Ziaur Rahman was synonymous with BNP, General HM Ershad symbolised the Jatiya Party, Khaleda Zia later stood for BNP, and Sheikh Hasina for Awami League. Parties seemed to have little independent existence beyond their leaders.

The impact of this reality is that MPs also exist largely at the pleasure of party leaders. While it is the voters who make or unmake an MP, that power, in reality, lasts only for a while. The moment the result of the polls is out, those who win turn their attention away from the voters and onto, not the party, but its leaders. What we call a parliamentary system thus operates more like a presidential form of government under the guise of a parliamentary form. This practice is not likely to change immediately, but the process of holding the party leader accountable by the party itself must begin, however modestly.

Another lesson that we must learn from our past is that in our political culture, a ruling party gives no importance to the opposition, except in devising how to divide, dismantle, or discredit it, and finally to oppress it in every possible way. The ruling party does not think of the opposition as a political competitor. This political culture must change. For good governance—and, philosophically, for its own success—the ruling party needs a strong opposition. Without an effective, vibrant and responsible opposition, Bangladesh is unlikely to sustain a functioning democracy.

There is, however, a contrary lesson too. We need a responsible opposition also. What we have often seen is a culture of "opposition for opposition's sake," not opposition for the benefit of the country, or for good governance, accountability, transparency, and efficient resource management, etc. Just as the ruling party thinks of the opposition as "enemy", so too does the opposition, resulting in trying to embarrass the government, scuttle its projects, or make processes dysfunctional. The most destructive practice that we saw evolve during the first term of Khaleda Zia's government is the culture of walkouts, followed by boycotts, and finally resignations. Unfortunately, this was later emulated by subsequent oppositions, too.

Much, therefore, needs to change as we begin anew. Above all, all political parties must contest the election, help ensure its peaceful conduct, and accept the outcome as the will of the people. The notion that elections are fair only when one wins and bad when one loses must be abandoned. In every election, not everyone can be a winner; there will be losers too, and that outcome must be accepted with grace, dignity and respect for the voters. So please put the country first, democracy second, and your victory third. If you win, congratulations. If you lose, congratulations as well, for you have honoured the people's verdict and helped restart our democratic journey.

Mahfuz Anam is editor and publisher of The Daily Star.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries, and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments