Poritosh Sarkar’s Orwellian Experience

The draconian Digital Security Act (DSA) has claimed its latest victim. On February 8, the Rangpur Cyber Tribunal sentenced Poritosh Sarkar, a Hindu teenager, to five years in jail for "hurting religious sentiments." Poritosh was sentenced under Section 31(1) of the DSA that criminalises publication and posting of any material "that creates enmity, hatred or hostility among different classes or communities of the society or destroys communal harmony", along with Sections 25(2), 28(2) and 29(1).

Poritosh was the first person to be convicted for the communal frenzy that led to the razing of 60 Hindu homes in Rangpur's Pirganj upazila on October 17, 2021. Most of the other accused in the case secured bail, while others are on the run. It appears Poritosh, a 10th grader at the time of the incident, belonging to an economically disadvantaged fishing family, is paying the price for an act that he firmly maintains he did not commit. Until the day of the verdict, no evidence was furnished to back up the state's claim that it was Poritosh who posted the message as his phone was destroyed beyond repair and the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) was unable to conduct forensic tests on it.

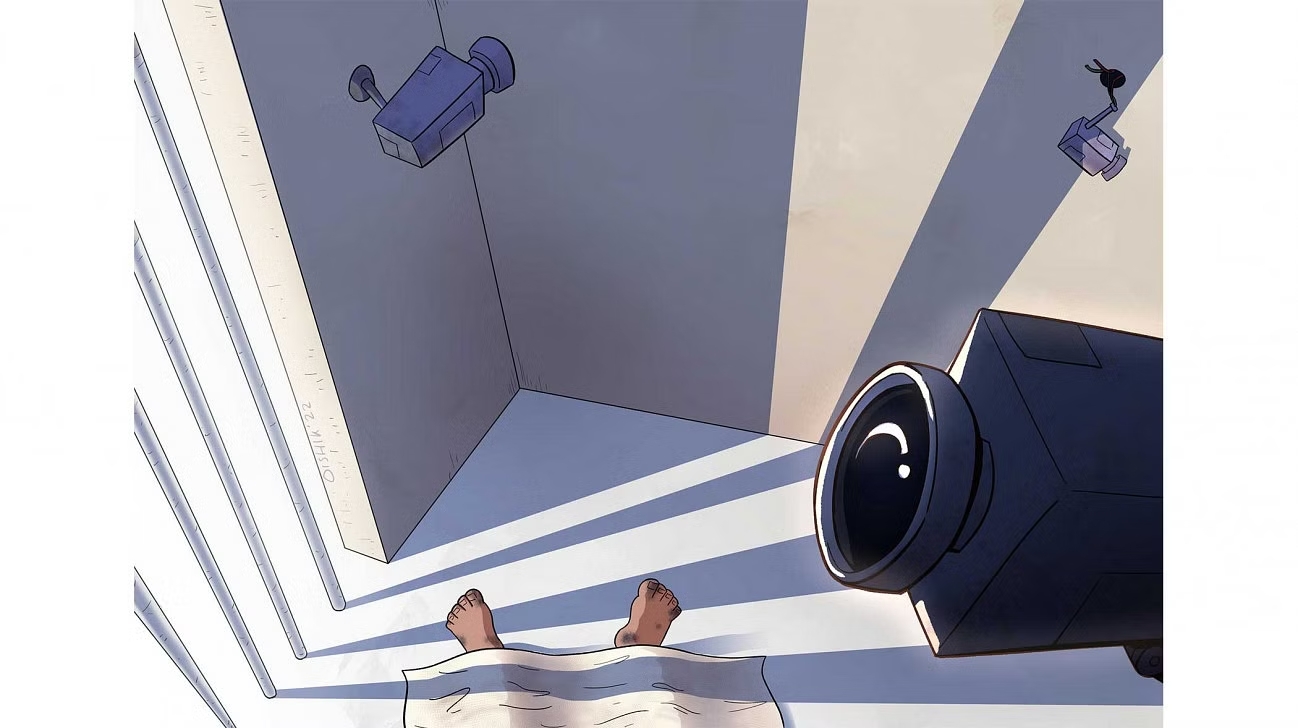

While Poritosh's sentencing raises concerns regarding the likely misapplication of the DSA, his treatment during detention has exposed the inhumane and brutal conditions that an accused may be subjected to under Bangladesh's criminal justice system. On February 5, speaking to The Daily Star at the Rangpur court premises, Poritosh informed that he had been kept in solitary confinement for eight whole months. The jail authorities claimed that the measure had been taken for Poritosh's own safety as the people who had set fire to the village were also in the same prison and were likely to harm him.

One may accept such flimsy reasoning in good faith; however, one is appalled by what Poritosh had further revealed, "I was not allowed to step out of my jail cell for eight months, not for a single day. There were no windows – just a vent at the top of the cell, which was blocked. I had no way of knowing if it was day or night from inside the cell. I counted the days by the meals being given to me."

The extent of mental harm Poritosh endured is further revealed when he said, "Not a single person spoke to me during those days. I tried talking to the guards, but they would not respond." For the first several months, he was given some books by the authorities, but even that was stopped. He said the desperate situation had driven him to consider dying by suicide. The extent of ill treatment and denial of his fundamental rights is further reinforced by the fact that his lawyers were unable to contact him when he was incarcerated.

While Poritosh's sentencing raises concerns regarding the likely misapplication of the DSA, his treatment during detention has exposed the inhumane and brutal conditions that an accused may be subjected to under Bangladesh's criminal justice system.

The most egregious breach of law in Poritosh's case was when he was placed in solitary confinement. Poritosh was a detainee, not a convict, and there is no scope under Bangladesh's criminal code to place a detainee in solitary confinement. Furthermore, Section 74 of the Penal Code says that "when the imprisonment awarded shall exceed three months, the solitary confinement shall not exceed seven days in one month of the whole imprisonment awarded." No less grievous was the mental harm that was inflicted on Poritosh in the form of denying him to communicate with any human being for eight long months. This was in gross violation of Section 29 of the Prisons Act, which states, "No cell shall be used for solitary confinement unless it is furnished with the means of enabling the prisoner to communicate at any time with an officer of the prison, and every prisoner so confined in a cell for more than 24 hours, whether as a punishment or otherwise, shall be visited at least once a day by the Medical Officer or Medical Subordinate."

The harsh treatment that Poritosh was subjected to raises several important questions. Firstly, why did the accused have to be in jail when those arrested for arson and communal violence were granted bail, including the muezzin of the village mosque who made calls for people to gather, and Saikat Mandal and Ujjal Hossain who were instrumental in triggering the rumour? Secondly, if the jail authority's justification for keeping Poritosh safe is taken at face value, was solitary confinement (reserved for hardened criminals) the only choice? Could he not be sent to some other facility? Thirdly, Doesn't the claim that the detainee was likely to be harmed within the jail compound also expose their failure to ensure the prisoners' safety?

Fourthly, under what grounds was the accused denied access to his counsel, a right guaranteed under the constitution of the republic? And finally, what prompted the sessions judge of the cyber tribunal to send Poritosh back to prison on February 5, overriding the bail granted by the High Court, even though no judgment was passed on the case at that time? How could the conviction warrant be issued even before the accused was sentenced?

Clearly, the state has a case to answer on all of the counts above. It is unfortunate that after nearly 52 years of independence, such blatant acts of state crime under the rubric of DSA committed against a teenager belonging to a minority community don't merit any discussion in the national parliament, nor are they condemned by the otherwise vocal champions of the spirit of Liberation War and the guardians of national conscience. The silence of the minority faith-based groups and the human rights and child rights organisations is also baffling, and so is the ineptness of the progressive liberals who occasionally care to issue statements or embark on fact-finding missions on matters of their priority.

Defending rights entail taking principled position against all forms of violations. Our collective failure to stand up for Poritosh Sarkar makes us culpable for the grave wrongs done to him.

The author acknowledges the support of Rezaur Rahman Lenin and Zyma Islam.

Dr CR Abrar is an academic with interest in human rights issues.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments