What's so wrong with hundi?

What is the reason behind hundi's existence? Why is it considered problematic, if other informal money transfer mechanisms aren't considered the same? And if hundi is so wrong, why aren't the authorities holding the policymakers who created the precondition responsible?

It is the central bank which has been artificially fixing defective exchange rates for the US dollar since the late 2010s – an act in violation of its commitment articulated in the Bangladesh Bank (Amendment) Act of 2003, which targeted to make the dollar's value float based on the demand and supply in the market. The central bank's deviation from the policy commitment – or, more specifically, taka's artificial overvaluation as a false sense of economic vigour for at least five years since 2016 – is the main reason why hundi-makers mushroomed at home and abroad. Remitters are like any other economic agents who will try to minimise cost and maximise revenue while sending their hard-earned dollars to their families in Bangladesh. In so doing, they encounter two avenues: the formal banking channel and the private-agent based informal channel, which we call hundi.

Remitters have every right to do cost benefit analysis, and many of them resort to using hundi simply because this channel offers greater value for their hard-earned wages. There are apparently five reasons to explain why.

First, official channels give inferior exchange rates to remitters – always less than what's given by hundi-makers. Second, hundi-makers charge no fees, whereas banks do. Third, hundi money reaches the family much faster than through banks. Fourth, women from villages fear entering banks and find understanding the procedure of remittance encashment challenging. Five, the banks in towns are often far away from their villages.

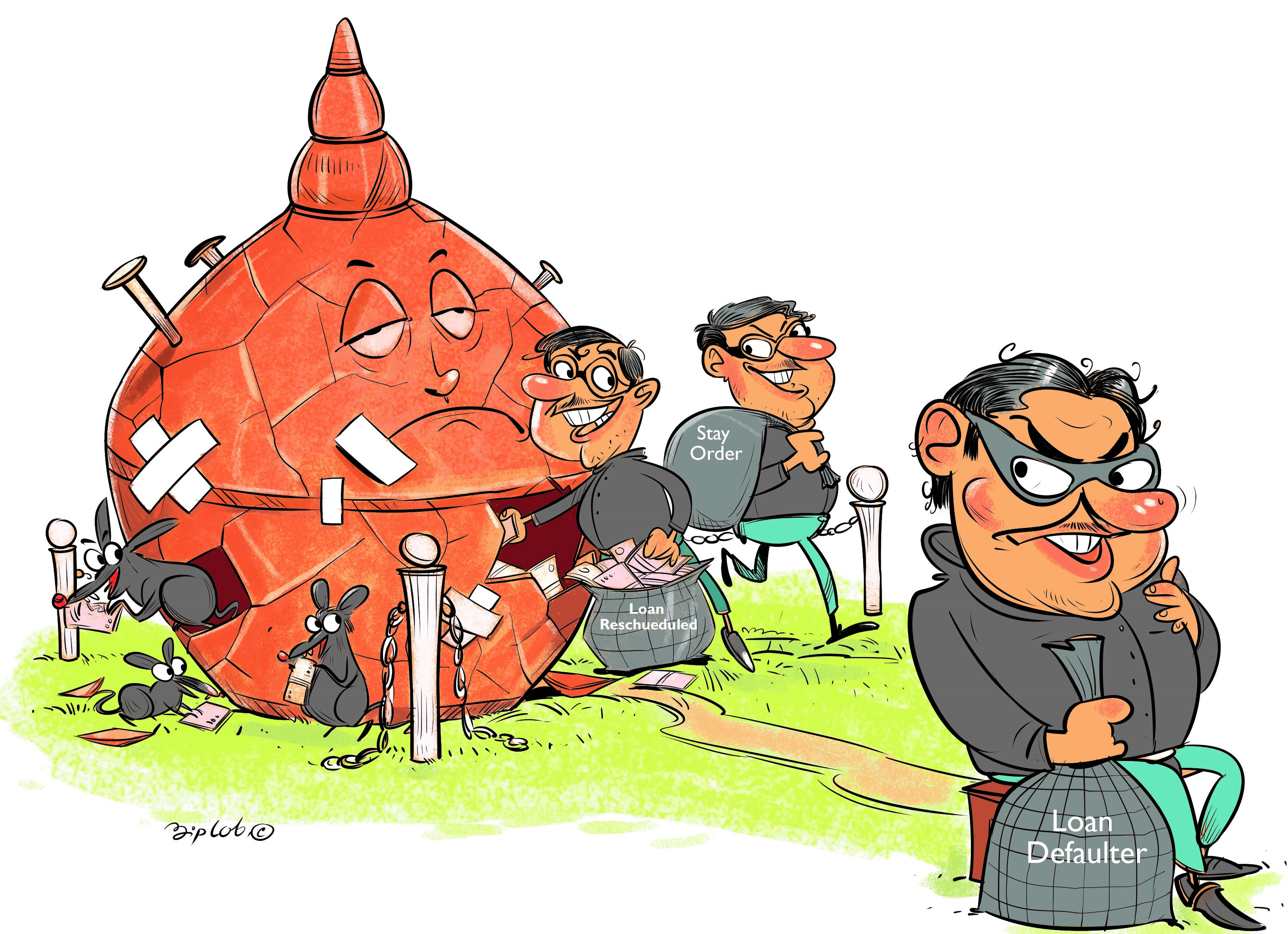

In contrast, these women are quite comfortable dealing with hundi agents living in their villages; they can easily draw the money from mobile financial services (MFSs) such as bKash in their village market. How would Korimon understand that taking money from Khedmat Mia is a financial irregularity in a country where bank looters are plundering millions of taka and getting repeated waivers from the central bank? If big default loans are redefined as new regular loans, and if money launderers are encouraged by the budget to become legal, why can't hundi-makers be redefined as remittance facilitators? Why are the hundi-makers chased by the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) and arrested when police fail to arrest numerous money launderers roaming around us with huge political clout?

When the Bangladesh Bank's faulty remittance policy, tardiness, and inadequate banking network engender the mushrooming of hundi-makers in an ever-growing trajectory, how many CID officers and how much resources can the government devote behind chasing them? Would that be worth it, while other erudite criminals are roaming around in society?

Hundi emerged in the 12th century in India. The British rulers found it a waste of energy to eradicate the hundi business since it is an informal bill of exchange – just like village mahajans earn abnormal profits by lending at exorbitant interest rates. And the British didn't attempt to arrest mahajans. Economists agree that the hundi business wouldn't have prevailed so long, had it not had strong economic underpinnings.

Korimon's husband Sattar works in a restaurant in New York City where Bangladeshi exchange houses would give him Tk 100 against one dollar. However, the exchange houses will charge USD 2 as a fee. Plus, Sattar requires both time and money to travel to Manhattan to hit the office. Sattar needs to buy a subway ticket, but his boss won't allow him to run for errands during the day. Then Sattar must fill out the form, waste a page of his chequebook, collect stamps, mail the envelope to the address in Manhattan, and wait for a week to hear that his money has been credited to Korimon's bank account. It sounds worse than the British system of money orders carried by the "Runner," as portrayed by poet Sukanta.

Let's add to this the weird nonmarket peanut – banks call it 2.5 percent incentive. So, Korimon will get Tk 10,250. Now, subtracting Sattar's cost for the fee and travel expenses or cheque page plus postal expenses, the net value that Sattar's family is getting against USD 100 is less than Tk 10,000 – say, Tk 9,800. However, Sattar knows one of his co-workers, Khedmat Mia, is a trusted hundi-maker and is willing to give Tk 10,600 for USD 100 – no strings attached. Sattar gives USD 100 to Khedmat Mia, who instantly calls his brother Keramat Mia in Nalitabari and instructs him to give that exact amount of money to Korimon bhabi within half an hour. Korimon is so happy to get the hassle-free remittance that gave her Tk 350 extra, while the Sattar family's overall gain through this hundi is more than Tk 800. Which path would Sattar choose, as a rational economic agent?

If the amount is USD 1,000, the additional gain is more than Tk 7,000. Both the satisfaction of speed and convenience are simply invaluable. It's a win-win situation for both parties. What is so wrong with that? The bankers and police will argue that they are illegal because they are avoiding the official channel. But poor Korimon doesn't have the guts to say that their official rates are undervalued, and the total mechanism is cumbersome as well as bureaucratic.

The Bangladesh Bank must address these areas to overcome the problems with hundi. The dollar's value must be market-based. The incentives are burdening the fiscal budget. They are now worthless given the high price for the dollar, and hence must be removed. Rather, the government can give some incentives to the exchange houses for enabling them to allow no fees for all sorts of remittances. Each bank must develop its own app for the electronic transfer of remittance funds as fast as possible. Instead of wasting energy on chasing or arresting hundi-makers, the central bank can think of including this network by giving them licences and thus devising more avenues to draw remittances from multiple sources. It's equivalent to the concept of agent banking, which tap USD 7.8 billion into the formal channel, will increase fiscal revenue, and thus will help the government address its fiscal incapacity. Let's convert a weakness into an opportunity.

Dr Birupaksha Paul is a professor of economics at the State University of New York at Cortland in the US, and former chief economist at Bangladesh Bank.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments