The interim has failed to curb inflation and unemployment

If the national election does take place in February, a new government will face dire quandaries for the economy, mainly in the lines of inflation and unemployment—the two notorious vices for any economy. As economics textbooks suggest, hitting these two culprits simultaneously is a terrible task because of the typical trade-off between them. As the central bank raises the policy interest rate to tame high inflation, high interest rates, in turn, increased unemployment by discouraging investments. If interest rates are slashed to boost investment and decrease unemployment, the ensuing cheap money will fuel the fire of inflation further up.

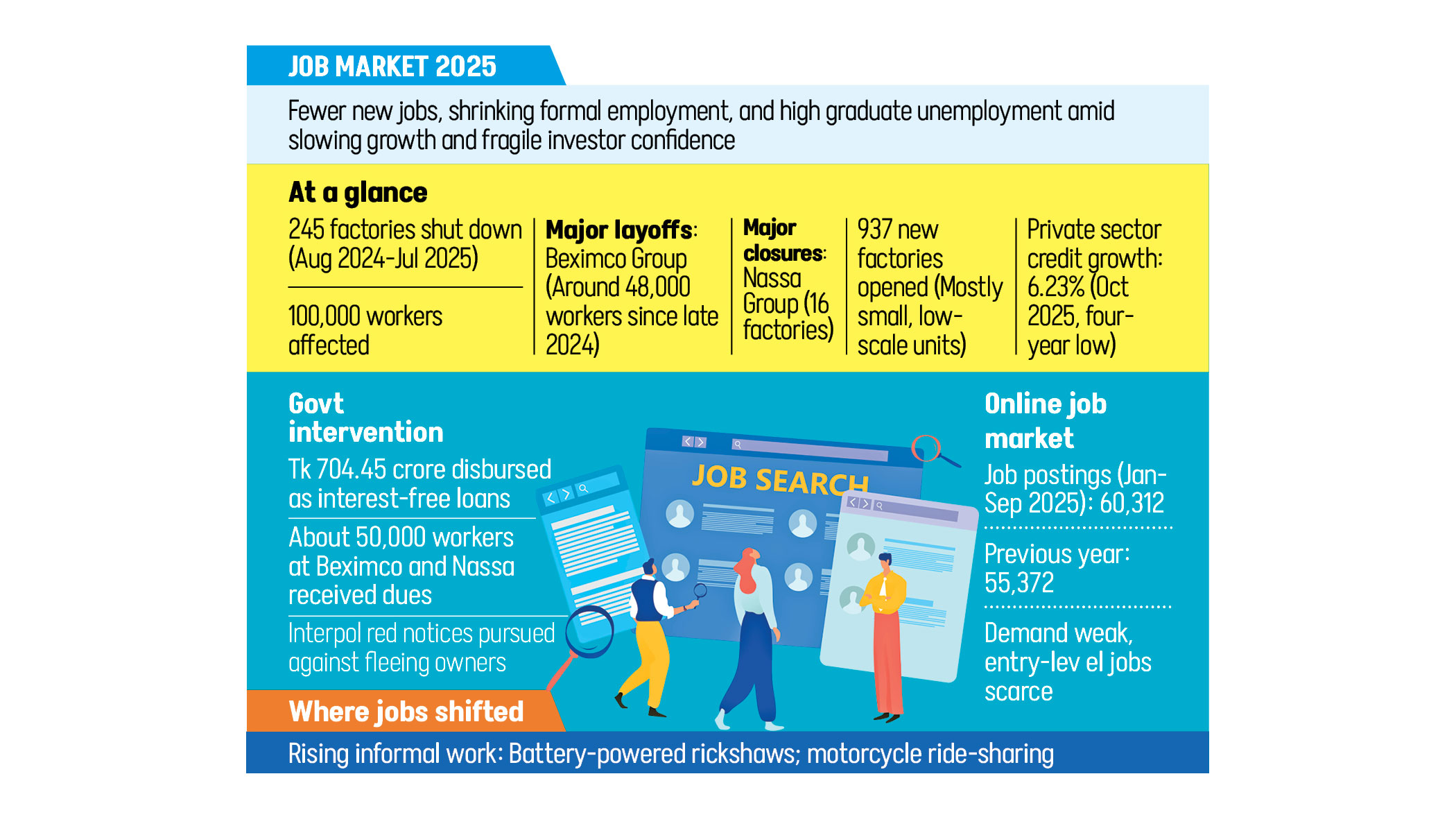

This situation is akin to reducing the speed of a car to minimse risks and thus enduring delays in hitting your destination. On the other hand, speeding up will increase the risk of accidents. Bangladesh's current situation with high inflation and rising unemployment is thus quite difficult to solve. Bangladesh Bank has raised policy rate to near 10 percent which has made credit expensive because other banks are charging lending rates at around 15 percent or higher. Private credit growth, which supposed to stay at around 15 percent or higher has now fallen to as low as around six percent—never seen in the last two decades. This puzzling conundrum rarely appears in the economy, heralding the advent of stagflation which Bangladesh's economy never saw in the last quarter century since 2000.

The interim government inherited an inflation of 10.87 percent in August 2024. It was 8.29 percent in November 2025. Achieving this drop in inflation after one and a half years cannot be considered as a big success for the interim government, when it is compared to neighbouring countries' success in inflation control. India's inflation, 6.21 percent in October 2024, fell to below one percent in November 2025, suggesting that price hikes are not a concern at all for India's consumers and investors. Pakistan's inflation, which rose to 38 percent in May 2023, fell below one percent in April 2025. Although it was 6.1 percent in November, it ascertains price normalcy given Pakistan's macro situation. Sri Lanka's inflation was 50 percent in March 2023, but its central bank made it fall so precipitously to 1.3 percent within six months. It was 2.1 percent in November 2025.

Despite achieving credible successes in external sector areas particularly foreign reserves, Bangladesh's central bank failed to display a success story similar to other South Asian central banks. Monetary treatments, including high policy rates above 10 percent, almost failed to tame inflation because of other rogue institutional failures such as extortions, mobocracy, fiscal debility, and declining loan recovery. Hence, 2025 has been marked by worsening economic conditions which will pose challenges to the new government's economic management capabilities in 2026.

Since unemployment was the triggering factor for the student-led July-August uprising, the interim government's main attention should have flowed into addressing this issue. That did not happen. Rather, the government's attention was sporadic and thus diluted with regards to economic aspects such as private investment, financial reforms, credit growth, women empowerment, rural opportunities, and above all law and order. According to the General Economic Division's State of the Economy 2025, the overall unemployment situation in 2024 has slightly deteriorated compared to 2023. The highest unemployment rate is 13.54 percent among university graduates as BBS labour force survey reports.

Much to people's disappointment, the trepidation of losing jobs took the centre stage rather than prospects of getting jobs or upliftment in the quality of jobs in the labour market. More than one lakh garment workers in Bangladesh lost their jobs over the past year following the closure of at least 258 factories, according to a new survey by the Asia Floor Wage Alliance (AFWA). Although the pace of job creation was often slow in Bangladesh where 84 percent jobs belong to the informal sector, the pace of job loss during the interim regime was high because of abrupt factory closures.

The new government must work on how to reverse this inauspicious pattern of factory closures and job losses. While the government is pleased to display significant export growth in FY2025, unrest and panic in the whole garments industry have remain prevalent. Agriculture, being only 11.15 percent of GDP, employs over 40 percent of the workforce, and that is not a good sign. Industry is the only sector that can generate high growth in both employment and output, and that side has remained excruciatingly disturbed during the interim regime.

The results of industrial perturbation have been manifested in three areas: i) around six percent growth in private credit; ii) an abrupt rise in unemployment; and finally iii) the unholy reversal in the so-far declining trend of poverty. Reports say that women job creation has been one of the slowest during the interim regime while it should have been the opposite as a nation strides forward.

It is worth mentioning that the interim government of 2007-2008 primarily focused on law and order without publicising big talks on reforms, and it succeeded in maintaining macroeconomic stability and people's deep sense of security. These two aspects are deeply missing in the current interim regime, making it a prime task for the next government of 2026.

Bangladesh's current growth performance, around four percent in FY2025 and expected five percent in FY2026, is much below its potential. The demographic dividend, which will expire for the nation by 2035, must be utilised quite properly to catch the last train of growth acceleration. Otherwise, it will be Bangladesh's both institutional and structural failures for not translating growth into inclusive development and prosperity. The new government's long-term target will be to rediscover the secrets of decent economic growth which will lower income inequality and regional disparity.

Dr Birupaksha Paul is professor of economics at the State University of New York at Cortland in the US.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries, and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments