Will the Democrats win after Biden’s withdrawal?

US President Joe Biden's decision to step aside as the Democratic Party's presidential candidate this fall has transformed American politics. It caps a historic July in the United States, one defined by far-reaching Supreme Court decisions and the attempted assassination of former President Donald Trump on the eve of the Republican Convention.

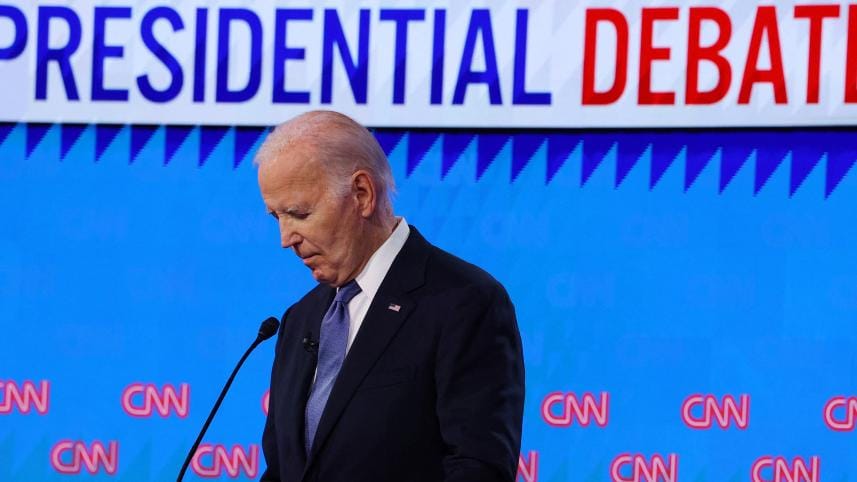

Biden's decision, urged by many Democratic Party officials and donors and favoured by many voters, was the right choice. In the wake of a debate widely viewed as a debacle for Biden, his age had made it all but impossible for him to make the case to the American people that he deserved another four years—and was making it impossible for him to make the case that Trump did not.

It is too soon to write about Biden's legacy, if for no other reason than that his presidency still has some six months left. But by stepping aside he has gone a long way toward eliminating the potential critique that by staying in the race he paved the way for a successor who shared little of his commitment to American democracy and the country's role in the world. Indeed, had Trump defeated Biden in November, as polls were forecasting, this would have largely overshadowed Biden's accomplishments as president.

The odds are strong that Vice-President Kamala Harris will be the Democratic nominee. Biden's endorsement will help her. But it does not settle matters, because Biden only has the authority to release party delegates committed to him, not to require them to support someone else.

So, the Democratic Convention in Chicago this August will be an open one, and the four weeks between now and then could go a long way toward determining what happens there. Harris could essentially run for the nomination unopposed, or one or more challengers might emerge. Assuming she prevails, the latter scenario might actually be to her advantage, as the process would further hone her political skills, help her be seen as a winner, and allow her to get out from under the shadow of an unpopular president.

The process would also shine a spotlight on the Democratic Party at a time when it needs to reintroduce itself to the electorate. This is essential, as Trump and Senator J D Vance, his pick for vice-president, promise to be formidable campaigners. And even if Harris were to run and lose to them, polls suggest that she would outperform Biden, improving Democrats' chances of winning the House of Representatives (keeping control of the Senate appears out of reach) and thus preventing Republicans from controlling the entire federal government.

Trump is slightly ahead of Harris in polls, but she could well get a boost in the next month as she steps into the spotlight. Harris's prosecutorial skills, which she honed as a prosecutor and later as California's attorney general, would serve her well in a campaign. She is well-positioned to take on the extreme anti-abortion stance of this Supreme Court as well as Vance. And she would benefit from the absence of a woman or a minority on the Republican ticket.

One unavoidable challenge, however, is what might be described as the Hubert Humphrey dilemma. In 1968, Humphrey, who was vice president at the time, won the Democratic nomination after the incumbent president, Lyndon Johnson, chose not to run for re-election. The words in Biden's withdrawal letter echoed many used by Johnson 56 years ago, the principal difference being that Biden put out his statement on X and Johnson appeared on national television.

The dilemma is this: how to appear loyal and take credit for what was popular about a presidency without being weighed down by policies that were unpopular. In 1968, it was the Vietnam War that complicated Humphrey's run, as he found it hard to distance himself from a policy that he had been associated with and from a boss who had little tolerance for disloyalty.

No single issue dominates public debate today, but there is still a need to differentiate the Democratic nominee from Biden, as incumbency has become a burden at a time when many seek change. Anyone doubting this only needs to look at recent election results in South Africa, India, the United Kingdom, and France.

This means that the Democratic nominee, whether Harris or someone else, would do well to embrace the Inflation Reduction Act and the CHIPS and Science Act, efforts to combat climate change and defend democracy, access to abortion and birth control, and military assistance to Ukraine. But it also suggests that the candidate might want to distance themselves from a Middle East policy seen by many Americans as too pro-Israel, and from policies on the border and crime viewed by many as too lax.

If Harris is the Democratic choice, her selection of a running mate will matter. Several Midwestern states are likely to be decisive in November's election, and there is a large pool of independent voters to be won over. Governors Gretchen Whitmer of Michigan, Josh Shapiro of Pennsylvania, Andy Beshear of Kentucky, and Roy Cooper of North Carolina would presumably be considered, as would several members of Biden's cabinet.

Perhaps the only thing that is certain is that less is certain after Biden's stunning announcement. One thing is clear, though: the outcome of the presidential election will matter enormously for the US and the rest of the world. This is not normally the case, as the candidates' similarities tend to outweigh their differences. Not so this time. The differences are profound, making it difficult to exaggerate just how much is at stake when Americans vote this November.

Richard Haass, President Emeritus of the Council on Foreign Relations and a senior counsellor at Centerview Partners, previously served as Director of Policy Planning for the US State Department (2001-03).

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments