Will the next government deliver truth and healing for victims?

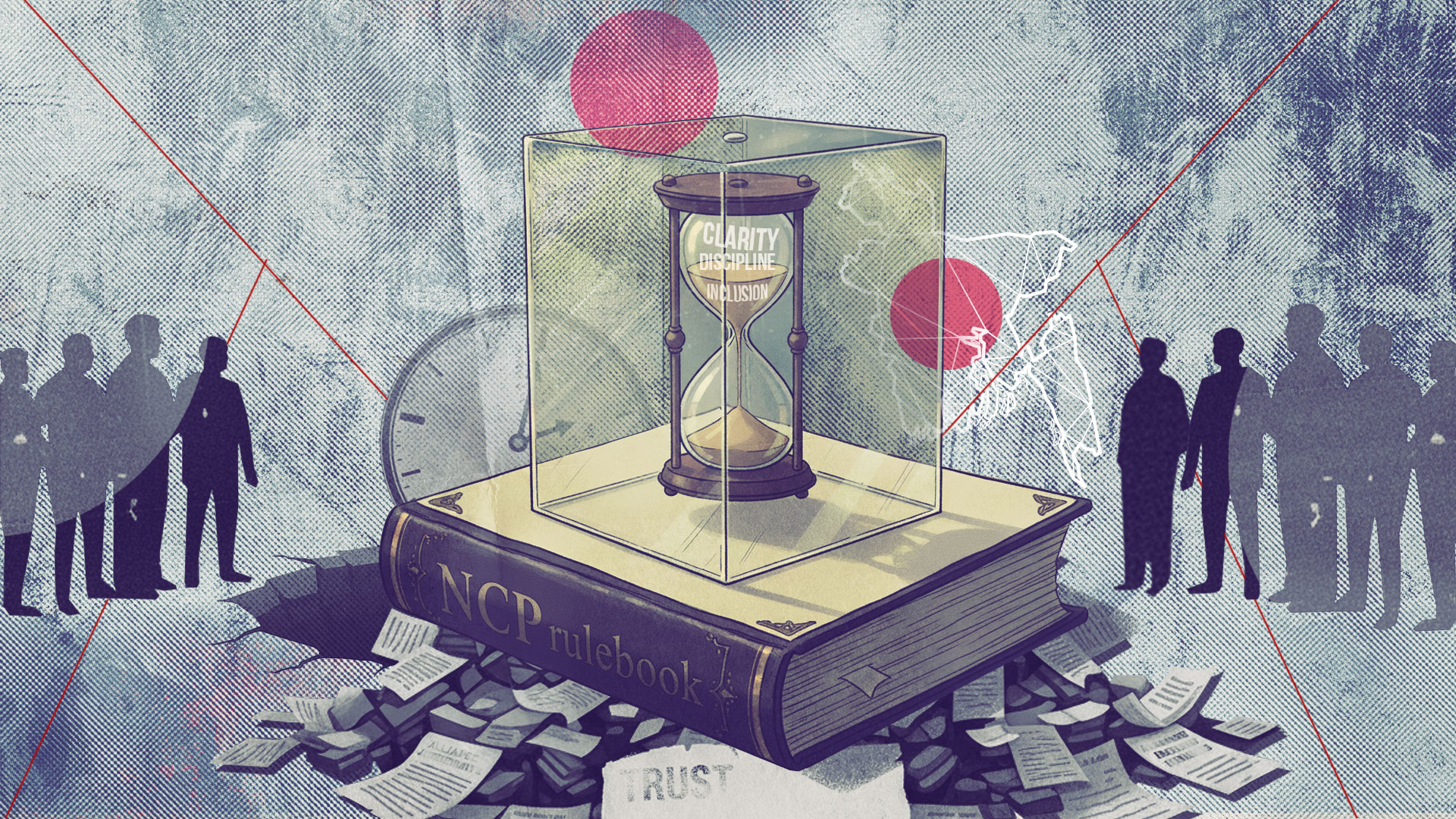

As Bangladesh moves towards the much-awaited election in February, the central question confronting the country is no longer whether grave abuses occurred during Awami League's rule of 15 years, but whether the next government will address the needs of victims of those abuses or repeat the mistakes seen in other transitional societies, where political compromise and selective justice weakened accountability, leaving victims without meaningful redress.

The past year or so saw important conversations in this regard. Victim consultations in Dhaka, involving survivors of the last regime, were held across political party lines and in the presence of various stakeholders. These engagements sought to build consensus around the need for a truth, justice, and healing process grounded in lived experiences. Political parties were encouraged to reflect on victims' healing, justice, and accountability needs in their election manifestos, recognising that transitional justice is not a peripheral concern but a core democratic obligation. Representatives from BNP, Jamaat-e-Islami, NCP, AB Party, and other parties also expressed willingness to incorporate these issues into their manifestos.

Building on these discussions, on December 12, the International Institute of Law and Development (IILD) and Bangladesh 2.0 Initiative organised a consultation with victims, their families, and relatives from the Rangpur division. It was structured around compassionate listening to understand the victims' diverse needs and justice aspirations. The participants shared their experiences and insights regarding enforced disappearances, custodial torture, extrajudicial killings, false cases, medical neglect, economic dispossession, and long-term psychological trauma. Families spoke of the fear that displaced them from their homes, of loved ones killed in so-called crossfire, of permanent disability, and of a justice system that repeatedly failed to respond. This process of sharing can contribute not only to documenting truth but also to healing.

Many victims also spoke of exhaustion. They described being asked repeatedly to recount their experiences in gatherings and programmes, which they found to be uncomfortable and re-traumatising. While recognising the importance of sharing their stories, they expressed frustrations that the government and wider society listen without caring, and document suffering without acting upon it. This feeling only adds to their overall sense of uncertainty.

What victims shared in Rangpur closely echoes narratives that have emerged from earlier victim-led consultations held elsewhere. Suffering is acknowledged rhetorically, yet accountability is consistently deferred in the name of stability, order, or political transition. These recurring testimonies, across regions and victim groups, underscore why a truth and healing commission is urgently needed, and why it must be designed with integrity and a decolonial framework. As victims have repeatedly made clear, healing cannot occur if they are asked to forgive while perpetrators remain unidentified, unpunished, or shielded by political power. Reconciliation, however desirable as a national aspiration, cannot be forced upon victims without credible justice processes and enforceable accountability mechanisms. When reconciliation is prioritised over justice, it ceases to heal and entrenches silence.

The consequences of unhealed trauma since the birth of Bangladesh in 1971 are still being borne today. Political expediency and compromises made in the name of stability did not bring lasting unity. Instead, they embedded cycles of violence, politicised institutions, and normalised abuse by state actors.

With the next election approaching fast, the risk is that restorative transitional justice may once again be reduced to an unmet commitment. History is not only observing whether a new government takes office, but whether it chooses to break with the past. A credible Truth and Healing Commission—grounded in victim participation, linked to prosecutions where evidence exists, and accompanied by proper institutional reform and reparations—would signal a decisive departure from the "forget and forgive" approach.

The victims do not demand vengeance. They demand recognition, truth, accountability, and assurance for non-recurrence. If the next government fails to address those needs, it will only be repeating the cycle of injustice, perpetuating the suffering of those who have already endured so much.

Dr Muhammad Asadullah is an associate professor at the Department of Justice Studies, University of Regina, Canada.

Tajriyaan Akram Hussain is an advocate at the District and Sessions Judge Court in Dhaka, and a member of the National Elections Inquiry Commission.

Nousheen Sharmila Ritu is executive director of UK-based think tank Bangladesh 2.0 Initiative.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries, and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments