Why is our tannery industry stunted?

The raw materials used to produce garment items in Bangladesh have to be imported in huge quantities. Despite this dependence on imports, garments are our main export, owing massively to the patronage of the government. However, though in a similar vein, Bangladesh's tannery industry could not develop nearly as well, despite having a huge domestic supply of high quality rawhides.

In the last fiscal year, ready-made garments worth $46.99 billion were exported from Bangladesh, for which $15.99 billion worth of cotton, yarn, cloth, equipment, and various other raw materials had to be imported. On the other hand, despite having sufficient quantities of rawhide available within the country, the export of leather and leather products only amounted to $1.22 billion in the last fiscal year.

One of the main reasons behind the underdevelopment of the domestic leather industry is the non-compliance with Environmental, Social, and Quality (ESQ) standards. According to a study by the Bangladesh Small and Cottage Industries Corporation (BSCIC), four major factors are responsible for this: 1) low Central Effluent Treatment Plant (CETP) capacity in the Savar tannery estate; 2) lack of awareness among tannery owners about compliance; 3) mismanagement of solid waste; and 4) non-improvement of indoor environmental quality of tanneries. This is why the tanneries in Savar are not getting recognition from the Leather Working Group (LWG), a prominent international organisation that certifies a tannery industry as being sustainable. As a result, leather processed by Bangladesh has to be exported at a lower price to China instead of to Europe.

The pollution problem in the leather industry is a long-standing one. While at Hazaribagh, the tanneries used to dump about 21,600 cubic metres of liquid waste directly into the Buriganga River every day without treatment. To reduce this pollution of the Buriganga, the tannery industrial estate was built—at a cost of Tk 1,015 crore no less—in Savar's Hemayetpur under the leadership of BSCIC, with Tk 521 crore spent on constructing the CETP. Although the tanneries were moved from Hazaribagh to the Savar Tannery Industrial Estate in 2017, the industry has still not been freed from pollution because the CETP—which was built at a hefty cost and over nine years (instead of the initial timeline of two years)—is not capable of fully treating all types of tannery waste. And this is a sign of extreme negligence and failure on the part of the authorities.

Although 42,000-45,000 cubic metres of waste are generated daily during the peak Eid-ul-Azha season, the treatment capacity of the CETP is only 25,000 cubic metres per day. Moreover, even this quantity of waste is not treated properly because CETP lacks a salt treatment unit. The amount of chromium waste is 5,000 cubic metres, but the capacity of the chromium recovery unit is only 1,050 cubic metres per day. There are also deficiencies when it comes to solid waste management. Meanwhile, the BSCIC has dug ponds for solid waste management, which does not align with environmental standards. As a result, while Buriganga was the one being polluted by the tannery industry in the past, the Dhaleswari River has become the new victim of the same.

Of course, in addition to the BSCIC, tannery owners themselves are also responsible for ESQ non-compliance. According to BSCIC research, the LWG gives out 1,710 points under 17 topics in the assessment protocol, of which 300 points are related to central waste management. The remaining 1,410 points are for operating permits, social responsibility, traceability, energy consumption, water usage, air and noise emissions, chemical management, and operations management. All of these are the sole responsibility of tannery owners. For example, according to the Bangladesh Environmental Conservation Rules, 2023, the water discharge per ton of rawhide processing should not be more than 30 cubic metres (or 30 tons). However, the tanneries use 50 to 60 tons of water, resulting in wastage and creating additional pressure on the CETP.

According to a study by the Solidarity Center, an international organisation working on labour rights, more than 70 percent of tannery workers in Bangladesh suffer from various health problems due to environmental pollution.

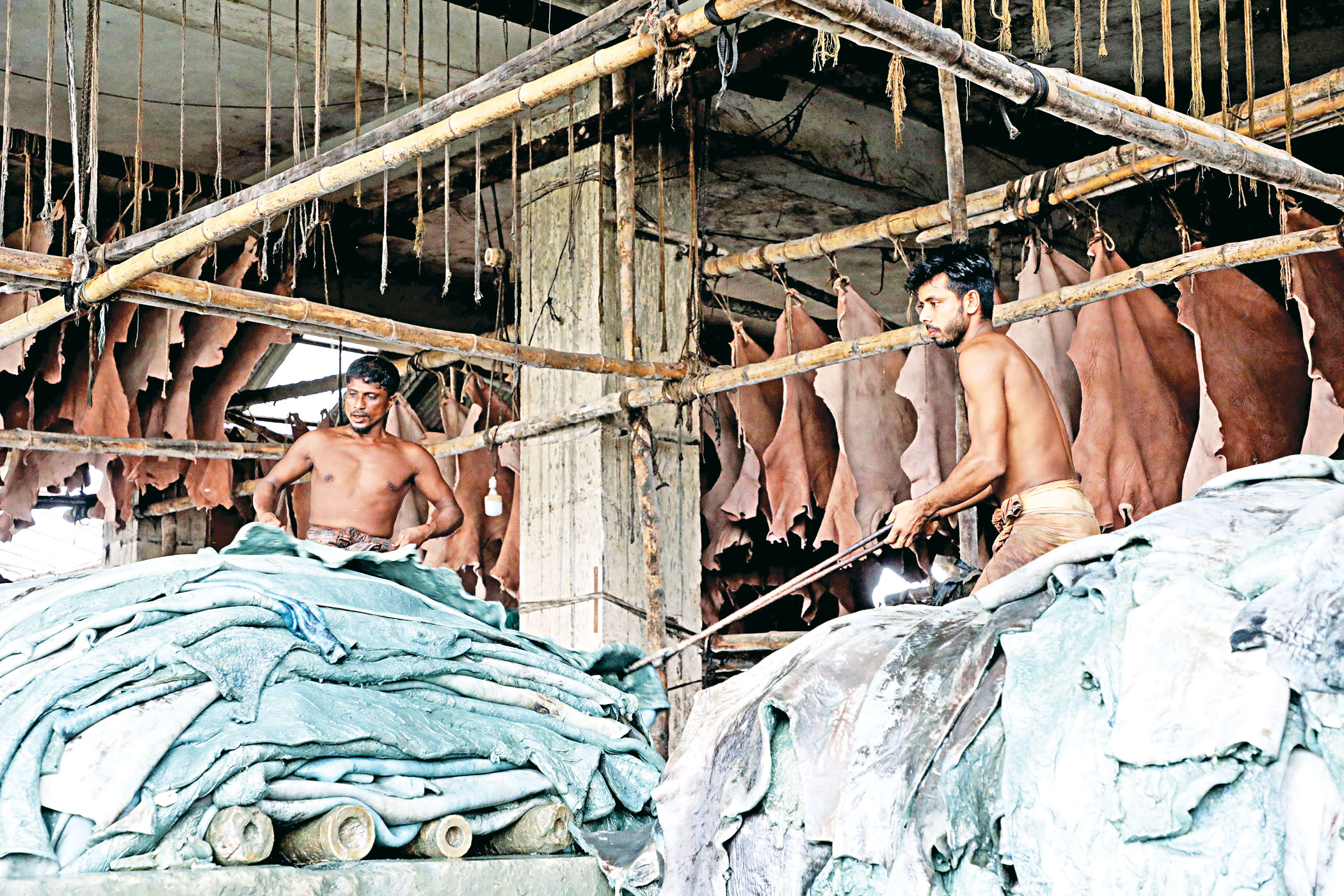

Besides environmental compliance, social compliance is another crucial factor in terms of which Bangladesh's tanneries are lagging far behind. Shifting the tannery industry from Hazaribagh to Savar has not solved the problem of poor working conditions, as most of the tanneries do not comply with local and international labour laws and also do not maintain minimum occupational health and safety standards. Environmental pollution from the tanneries also affects workers' health, living conditions, income, and working environment. According to a study by the Solidarity Center, an international organisation working on labour rights, more than 70 percent of tannery workers in Bangladesh suffer from various health problems due to environmental pollution.

According to another survey conducted jointly by the Bangladesh Labour Foundation and Research and Policy Integration for Development (RAPID), most of the tannery workers have no formal employment contracts and more than half of the workers receive wages less than the industry minimum of Tk 13,500. Due to environmental pollution and an unsafe working environment, many workers also suffer from skin diseases, shortness of breath, stomach ailments, and headaches. Most concerningly, three-quarters of those interviewed for the study said they work without proper protective gear, and 79 percent cited lack of training on how to use chemicals safely for tanning work.

Against this backdrop, tannery owners' compliance with the ESQ standards itself will be helpful in acquiring LWG certifications. Tanneries can also set up their own ETPs in order to produce leather in an environmentally friendly manner. For example, one tannery in the Savar industrial estate and five others outside the estate have received LWG certificates by installing their own ETPs and complying with the ESQ standards. These tanneries also have good business because they have the LWG certification. A recent study by The Asia Foundation found that the likely nominal cost of 10 years' investment in becoming LWG-certified for an individual tannery in Bangladesh can range between $30,908 to $87,226—depending on the current level of compliance—the estimated benefits of which could range between at least 1.05 to 3.15 times the cost likely to be incurred.

Bangladesh's leather is well-known for its good qualities of fine grain, uniform fibre structure, smooth feel, and natural texture. With the annual supply of 350 million square feet of high quality domestic leather, the potential for the growth of the leather industry in Bangladesh is promising, to say the least. But the development of this industry has been stalled by the negligence and mismanagement of government authorities and also due to the short-term, profit-seeking attitude of tannery owners. Until the government and the tannery owners realise their shortcomings and duly prioritise complying with ESQ standards, our leather industry will not develop sustainably.

Kallol Mustafa is an engineer and writer who focuses on power, energy, environment and development economics.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments