Why must workers always take to the streets for unpaid wages?

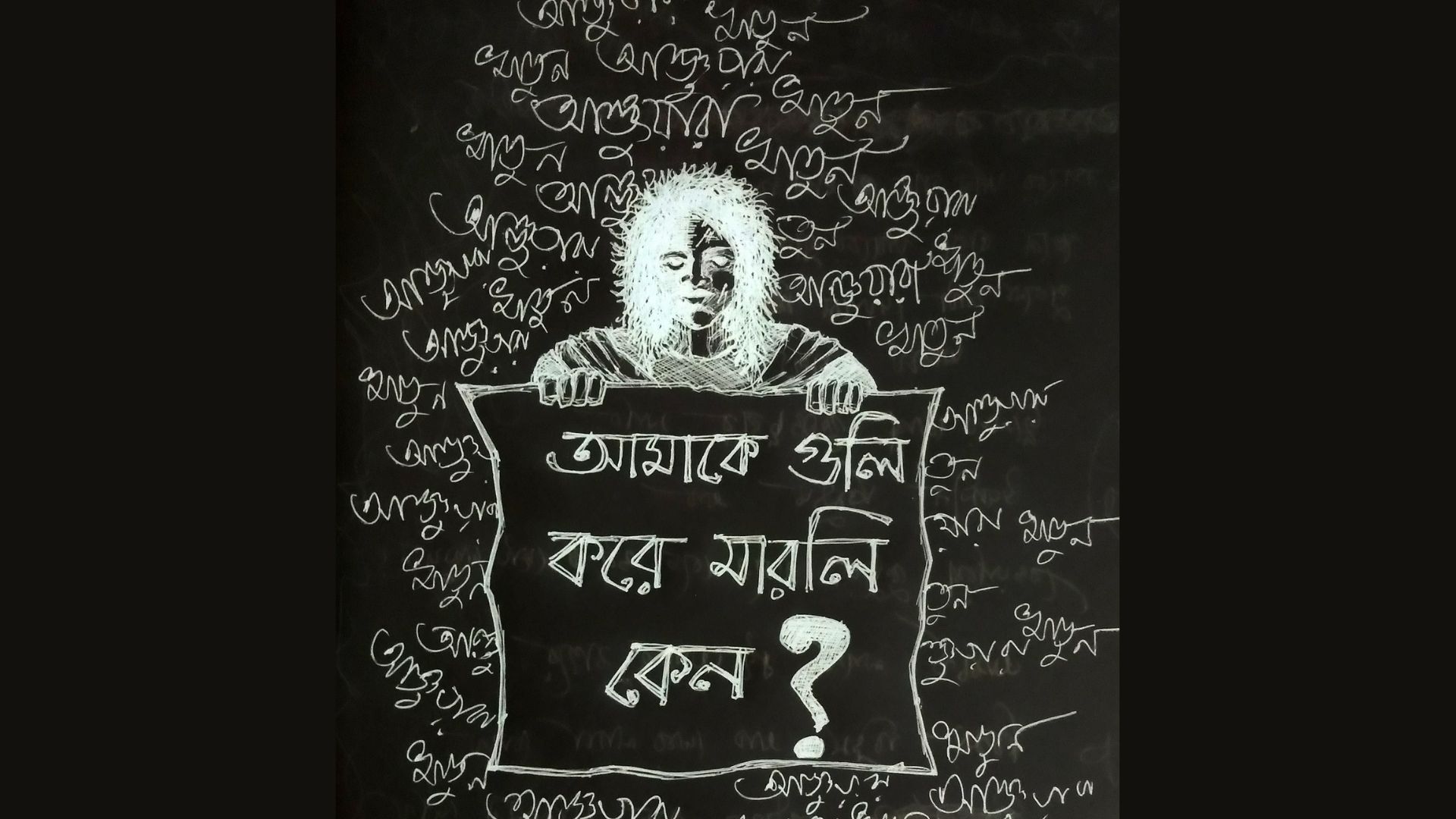

When I reached the Shram Bhaban in Bijoy Nagar, Dhaka on the evening of March 25, workers from Apparel Plus Eco Ltd and TNZ Apparels Ltd were organising iftar on the floor of the building's veranda. Their arrangement was simple, with chhola-muri. They looked exhausted. On the one hand, they had been fasting all day, and on the other, they had been attacked and beaten by police that day while protesting for their unpaid wages and Eid bonuses to be cleared. Several of them were injured and taken to the hospital, with one of them suffering a bone fracture.

Exhaustion could not suppress their anger when they spoke about their long deprivation, however. About 800 workers and employees of Apparel Plus Eco, owned by the TNZ Group, were yet to be paid three months' salaries and other dues, while about 2,600 workers of TNZ Apparels, owned by the same group, were due two months' salaries and other allowances. They first staged their protest in front of the factory in Gazipur and later in front of the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA) building in Uttara. On March 11, at a tripartite meeting held at the Shram Bhaban, presided over by an additional secretary of the labour ministry, in the presence of the workers, the owners of Apparel Plus Eco, and the BGMEA representatives, it was decided that the outstanding salary for January would be paid by March 20 and the February salary and Eid-ul-Fitr bonus by March 25.

Then, on March 17, a multi-stakeholder meeting held at the Department of Inspection for Factories and Establishments (DIFE) with workers, factory owners, BGMEA, industrial police, and DIFE representatives, changed the previous decision and decided that the salaries for the first halves of February and March would be paid by March 25, and the salaries for the remaining halves of these two months would be paid by April 20. The production general manager of TNZ Apparels promised, in writing, to clear the workers' holiday pay by March 20, the February arrears by March 25, and the Eid bonus by March 27.

But the workers were not paid the holiday pay by March 20. Now, due to the pending wage for two/three months, the workers are unable to pay their rent and grocery store dues. They are forced to live a subhuman life of half-starvation. As a result, they were forced to take a stand in front of the Shram Bhaban. But labour department officials did not take any action to implement the decision on the workers' payment made in their presence. Hence, the workers resorted to surrounding the labour ministry to make their voices heard, and ended up getting beaten up by police.

Many other ready-made garment (RMG) factory workers have been forced to take to the streets to demand unpaid wages. Workers and employees of Style Craft Ltd in Gazipur have been protesting in front of the Shram Bhaban since March 18. On March 23, a 40-year-old worker named Ram Prasad Singh fell ill and died during the sit-in protest.

Nearly 250 workers of Roar Fashion Ltd have been protesting in front of the BGMEA building in Dhaka since March 23, demanding a month's unpaid salary and layoff compensation. Workers of Hagh Knitwears in Gazipur took to the streets on March 25 morning, demanding three months' unpaid wages and Eid bonus. Workers from Thianis Apparels and MS Garments Ltd in the Chattogram Export Processing Zone staged separate protests on March 25 demanding salaries and Eid bonuses.

This issue of not clearing salaries and bonuses on time is not limited to just a few specific factories. According to a Prothom Alo report, as of March 24, out of 2,107 operational RMG factories that are members of BGMEA, 344 factories had not yet paid bonuses. Only 84, or four percent, of the RMG factories paid 15 days' salary for the current month. Meanwhile, only 50 percent of the 750 operating knitwear factories have paid bonuses. Earlier on February 12, the Tripartite Consultative Council (TCC) meeting decided that all outstanding salaries and bonuses of the workers would be paid by Ramadan 20 (March 21), along with at least 15 days' salary for the current month. But due to the lack of government oversight, many factory owners did not implement this decision on time, resulting in increasing protests.

The commerce ministry also warned of potential unrest at about 500 RMG factories over the payment of salaries and festival allowances before Eid, of which 36 factories were identified as particularly risky. The question is, did the government properly monitor those risky factories? Were the factory owners contacted and briefed about the situation? Does the government have any data on which factories are paying the salaries and bonuses, and when?

The issue of RMG workers not getting paid before Eid is not new. Every year during the previous government's tenure, we saw workers in the country's highest foreign exchange earning industry taking to the streets demanding salaries and bonuses to be paid before Eid.

After the mass uprising in July-August last year, in which a large number of working-class people participated, it was expected that these trends would cease to exist; that the interim government that came to power after the uprising would ensure the basic rights of workers with responsibility and compassion. But the government did not take appropriate action in time. In the face of protests, on March 25, it banned the owners of 12 RMG factories from travelling abroad over the non-payment of workers' dues—a much delayed decision.

This ban will not be effective for factories whose owners are already abroad, like the owner of TNZ Group. However, they have assets, including factories, in the country. To force uncooperative owners and their local representatives, strict legal action must be taken, including auctioning their assets. Besides, the government could have forced the BGMEA and BKMEA to form a special fund with contributions from the owners, so that if a factory owner faces a financial crisis, they can take a loan from the fund without interest to pay workers' salaries. For RMG factory owners, whose export earning is more than $36 billion per annum, forming such a fund should not have been difficult.

Unfortunately, even in the post-July uprising reality, we are still seeing the same old trends. There is no systemic way of resolving the workers' grievances, which is why they are still forced to take to the streets to make their demands heard again and again. And then there are cases of police attacks on the workers who take to the streets. Although the law enforcement agencies have been ineffective in preventing mob violence, they have been often aggressive towards people from different walks of life, including teachers, students and workers coming out on the streets to demand their rights. The police attack on RMG workers marching towards the labour ministry demanding unpaid wages is the latest example of this tendency.

In the post-uprising era, many changes and reforms are being discussed, but the reality of the workers has not changed at all. Will it, ever?

Kallol Mustafa is an engineer and writer who focuses on power, energy, environment, and development economics. He can be reached at kallol_mustafa@yahoo.com.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments