Why hasn't life changed for Bangladesh's visually impaired?

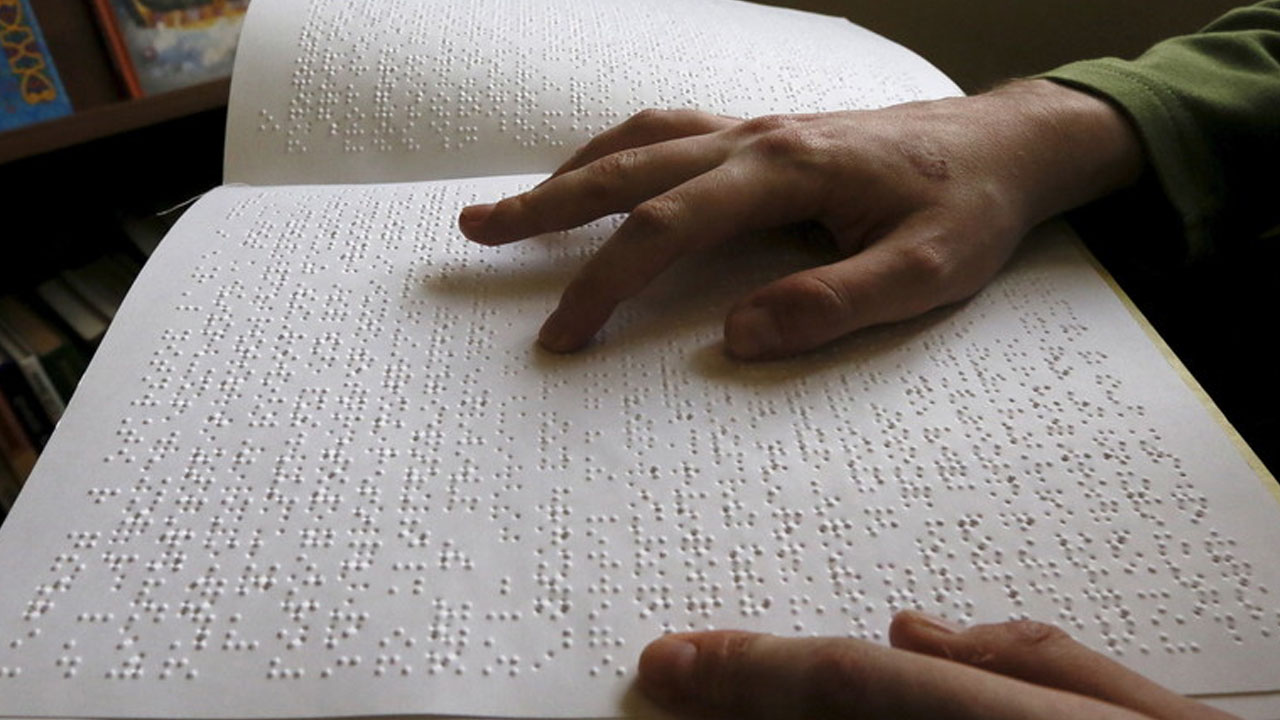

The third anniversary of Bangladesh's accession to the Marrakesh Treaty on September 26 is a pivotal moment to reflect on the progress and challenges in improving access to literature for persons with print and visual disabilities. Three years ago, Bangladesh took a historic step by joining the treaty and signing a promise to combat the pervasive "book famine"—a severe shortage of published works in accessible formats such as Braille, audio books, and digital text. However, progress remains frustratingly slow for a majority of the visually impaired and print-disabled individuals in Bangladesh.

The Marrakesh Treaty, administered by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), was created to ease copyright barriers that prevented the production and international sharing of accessible format books for people with print disabilities. Print disabilities cover a range of conditions, including blindness, low vision, and physical or perceptual impairments that make reading traditional printed text impossible or very difficult. By allowing authorised entities to reproduce and distribute printed works in formats such as Braille, large print, and accessible digital files without copyright infringement, the treaty holds the promise of opening the literary world to millions previously excluded.

Bangladesh's accession to the treaty in 2022 triggered widespread optimism among organisations advocating for the rights of the visually impaired, such as the Visually Impaired People's Society (VIPS). The ratification was seen as a landmark step toward fulfilling commitments to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) and the Sustainable Development Goals related to inclusive education.

However, we are yet to realise the practical benefits of the Marrakesh Treaty. The critical legal framework for implementation, namely the amendment of the Copyright Act, 2000, has faced significant delays. Without these legislative changes, organisations and individuals remain in a legal limbo, legally unable to produce or import accessible books. This gap prevents the treaty's provisions from translating into meaningful access to educational and literary resources.

Bangladesh's 2020 National Blindness Survey reported approximately 1.43 million people with visual impairment. For this large population, accessible literature is not merely an academic concern but a gateway to education, employment, and social inclusion. Yet, the "book famine" continues, exacerbated by limited public awareness, media neglect, and insufficient government action to prioritise disability rights.

The challenge extends beyond legal formalities. Awareness about the treaty among policymakers, publishers, and the general public is minimal. Mainstream media coverage has been sparse, contributing to a lack of public pressure on authorities. Moreover, infrastructure for producing accessible materials—including trained personnel, technology, and funding—remains inadequate.

This neglect stems from a broader societal apathy toward the rights and needs of persons with disabilities in Bangladesh. Without comprehensive awareness campaigns and government-led initiatives, the treaty's potential remains underutilised. Empowering persons with disabilities requires not just legislative compliance but active engagement with community education institutions and technology providers.

Bangladesh has a strategic opportunity ahead of it to refocus on disability inclusion. Amendment of the Copyright Act to incorporate the treaty's exemptions and protections was an essential first step. However, effective implementation demands governmental commitment to resource allocation and partnerships with civil society and international entities. Establishing accessible libraries, ICT labs, and multimedia platforms for distributed accessible resources would significantly enhance capacity. Raising public awareness through media and outreach campaigns will foster societal acceptance and support.

Though focused on literary access, the Marrakesh Treaty holds wider implications for Bangladesh's development. Expanding access to knowledge and education empowers persons with disabilities to participate more comprehensively in the workforce and civic life, thus contributing to a more inclusive, knowledge-based economy. This fosters innovation, diversity, and economic growth—goals aligned with Bangladesh's development.

The treaty also promotes transparency and accountability. Accessible legal and governmental materials enable citizens with print disabilities to engage in informed civic participation, promoting democratic inclusivity. Equally important, the increased visibility and empowerment of persons with print disabilities challenge societal stigma, fostering respect for diversity and human rights.

The European Accessibility Act (EAA) 2025 offers valuable lessons for Bangladesh and underscores the global trend toward comprehensive accessibility legislation. The EAA, which became legally binding on June 28, harmonises minimum accessibility standards across EU member states for products and services critical to people with disabilities, including digital content, e-books, smartphones, websites, banking services, and public transport.

The EAA specifically mandates that digital publications be accessible, addressing the core barrier of inaccessible reading materials faced by people with print disabilities. By setting common standards, the EAA enables innovation and market access while ensuring people with disabilities can independently use technology and digital content.

Importantly, the EAA complements the Marrakesh Treaty by not only mandating accessible content but also requiring businesses to design products and services with accessibility integrated from the outset. This combined approach addresses both the supply and availability of accessible materials, tackling the historic "book famine" from multiple angles.

Bangladesh must break free from the inertia and fulfil the treaty's transformative promise, investing in accessible infrastructure and raising widespread awareness. Engagement with people with print disabilities, their representative organisations, publishers, and printing presses must be central to this process. Their voices and experiences will provide critical insights that can guide policy, legal reform, and service delivery to meet real needs effectively. Furthermore, Bangladesh should broaden its perspective by considering advances such as the EAA to build an inclusive society with full participation for all citizens.

Ayon Debnath is a development practitioner and campaign adviser at Royal Commonwealth Society for the Blind (Sightsavers). He can be reached at adebnath@sightsavers.org.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments