Why is Bangladesh in the grip of a sizzling heatwave?

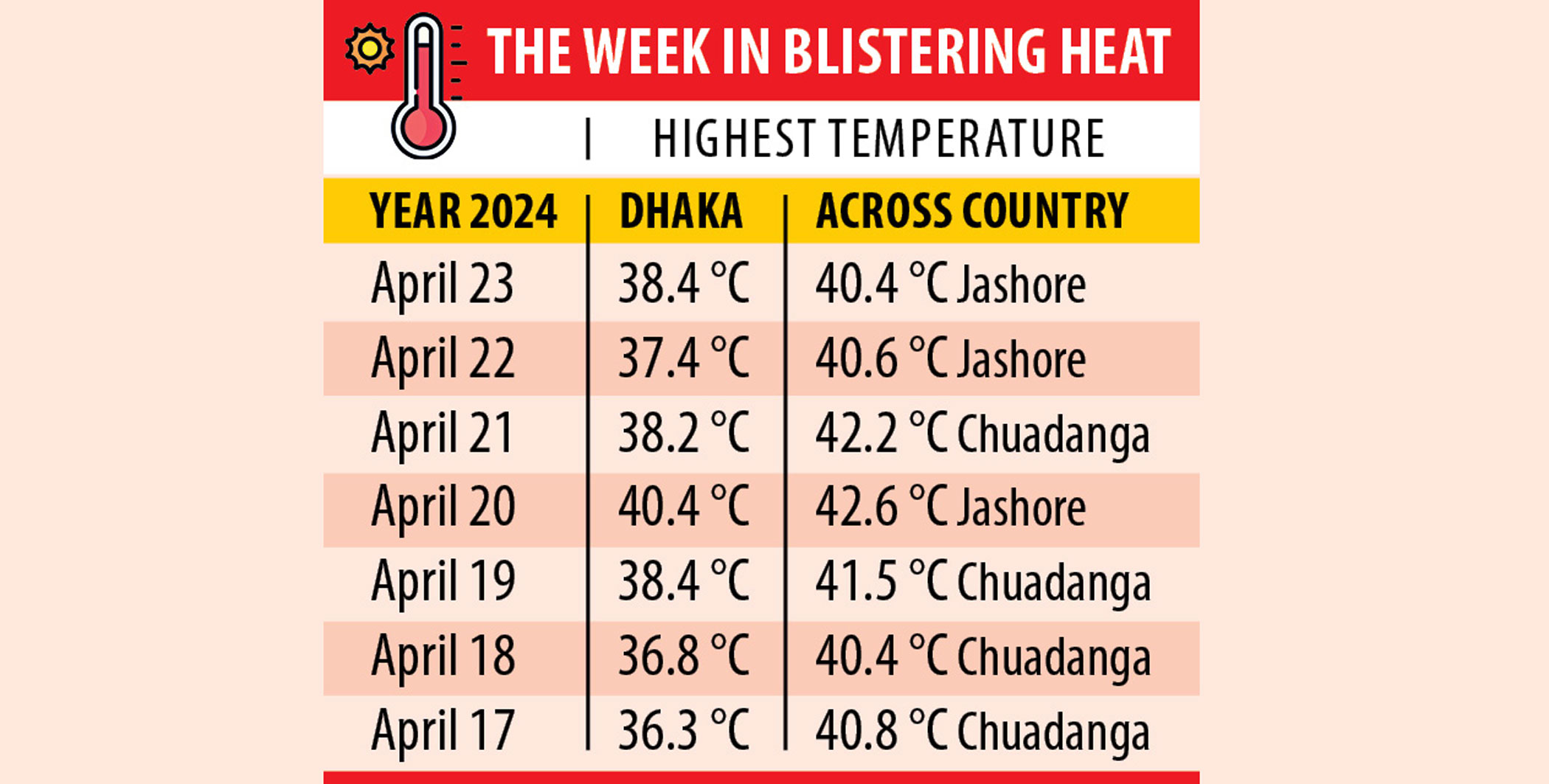

Millions of Bangladeshis are currently suffering from a punishing heatwave, with temperatures unceasingly hovering around 40 degrees Celsius. The temperatures are significantly higher than the country's average maximum of 33 degrees during April. The severe heatwave in Bangladesh has forced school closures, disrupted agriculture, and heightened the risk of heat stroke and other health complications.

Arguably, the prevailing severe heatwave in Bangladesh highlights concerns as climate change is spinning out of control. Heatwaves are one of the most dangerous manifestations of climate change. It has thrown out any sense that heat vulnerability follows a pattern limited to peak summer months. The deadly heatwaves would have been all but impossible without climate change. Instead, changing climatic patterns are accelerating the intensity, duration, and severity of heatwaves. Besides, Bangladesh's geographical location in the tropical region amplifies the effects of climate change.

Although the country contributes only a tiny fraction of global carbon emissions―0.56 percent, by one count―it is suffering disproportionately from their effects. Historical data reveals that the average daytime temperatures in Dhaka rose by approximately 2.75 degrees over the past two decades. This increase is much higher than the global average of around 1.2 degrees and already above the Paris Agreement's elusive goal of keeping the warming below 1.5 degrees. Experts predict that temperatures in Bangladesh will rise even more in the coming decades.

The primary reason for record heatwaves is a heat dome, which is a self-reinforcing, sprawling area of a persistent and strong high-pressure system that traps hot air in the upper atmosphere. It is called a heat dome because the trapped air in the system acts like a lid on a boiling pot. As the high pressure forces the stationary air in the dome to sink, it gets compressed and heats up, pushing temperatures upwards. At the same time, the dome squeezes clouds away, giving the sun an unobstructed view of the ground, which then bakes in the sunlight. Consequently, heat energy quickly accumulates and temperatures rise. The heat dome leading to extreme temperatures with high humidity, without any precipitation or rainfall, can last for weeks and make cities like Dhaka an oven under the open sky.

Tackling climate change is so much more than a technological challenge. Long-term strategies are necessary to address its impacts. Unfortunately, most strategies formulated by world leaders fail to strike at the roots of the problem: the harmful emissions of greenhouse gases. Their cruel idiocy in dealing with this extraordinarily complex problem is a band-aid solution.

Heatwaves are further exacerbated by the three-dimensional complexity of cities, disappearing lakes, and green spaces, among others, giving rise to the urban "heat island effect" that modifies some of the climatological factors in their immediate vicinity. With the loss of evaporative cooling normally provided by trees, lakes, and exposed soil, the gain of reradiated heat from the surfaces of high-rise buildings, narrow spaces between tall structures, dark surfaces, pavements, unshaded roads, sewers, air-conditioners, and industries that generate heat as a byproduct, the mean temperature of Dhaka and other cities in the country is on the rise. While the heat island effect does not produce dramatic temperature changes, over the years the cumulative effect is noticeable.

Another effect of climate change that augments heatwaves is balmy nights. During the last 50 years or so, overnight low temperatures during summer months worldwide have been warming at a rate nearly twice as fast as afternoon high temperatures, according to the state-run National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) of the US. The asymmetrical warming is because the greenhouse effect, responsible for global warming, operates round the clock, and nighttime temperatures are inherently more sensitive to climate forcing.

At this time of the year, Kal Baishakhi (nor'wester storms), a meteorological phenomenon characterised by rapid changes in weather, with strong winds, lightning, and thunderstorms accompanied by brief torrential rainfall, cools down the temperature considerably, thereby bringing relief from the scorching heat. However, the absence of Kal Baishakhi, another victim of climate change, is contributing to the oppressive heatwave.

In the 1980s, the duration of an April heatwave in Bangladesh was two to three days, and the temperatures were relatively mild, hovering around the mid-30s. Last year, the heatwave was intense, lingering for about a week and the highest temperature was 42.2 degrees recorded in Rajshahi in mid-April. The Union of Concerned Scientists warns that in the next few decades if greenhouse gas emissions continue to grow, we will see 20 to 30 days of very intense heatwaves.

Heatwaves raise the following question: what is the hottest temperature that humans can tolerate? The answer is a wet-bulb temperature (WBT) of 35 degrees Celsius. (The WBT takes into account both heat and humidity and hence, is not the same as the ambient air temperature.) Like most warm-blooded mammals, we cool ourselves by converting sweat into water vapour around a constant body temperature―not WBT―of 37 degrees. If WBT is above 35 degrees, it will impede our body's ability to cool itself down, thus creating conditions for life-threatening heatstroke. Fortunately, the WBT of Dhaka with a high of 40 degrees Celsius and 45 percent humidity is 30 degrees. Nevertheless, if the humidity becomes 70 percent, the WBT will reach the threshold value. Or if the temperature hits 50 degrees with 45 percent humidity, the WBT will be 35.2 degrees.

Tackling climate change is so much more than a technological challenge. Long-term strategies are necessary to address its impacts. Unfortunately, most strategies formulated by world leaders fail to strike at the roots of the problem: the harmful emissions of greenhouse gases. Their cruel idiocy in dealing with this extraordinarily complex problem is a band-aid solution. Moreover, since heatwaves are increasing at an alarming rate, their absurd policies and adaptation strategies will soon fall short of safeguarding people, as well as protecting the global infrastructure and the natural world.

The world is getting hotter, drier, wetter, and weirder. Decades of future heatwaves, wildfires, severe storms, floods, and long-lasting droughts are already baked into the system. Therefore, what we do now will determine whether we can slow global warming enough to avoid climate change's worst impacts. Indeed, with ethical discernment, collective action, and a shared dedication, we can cool down our planet and keep it inhabitable. But it will take time. In the meantime, we should better prepare ourselves for future heatwaves and help the most vulnerable people enduring the ongoing blistering heat.

Dr Quamrul Haider is professor emeritus at Fordham University in New York, US.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments