For whom is student evaluation of teaching necessary?

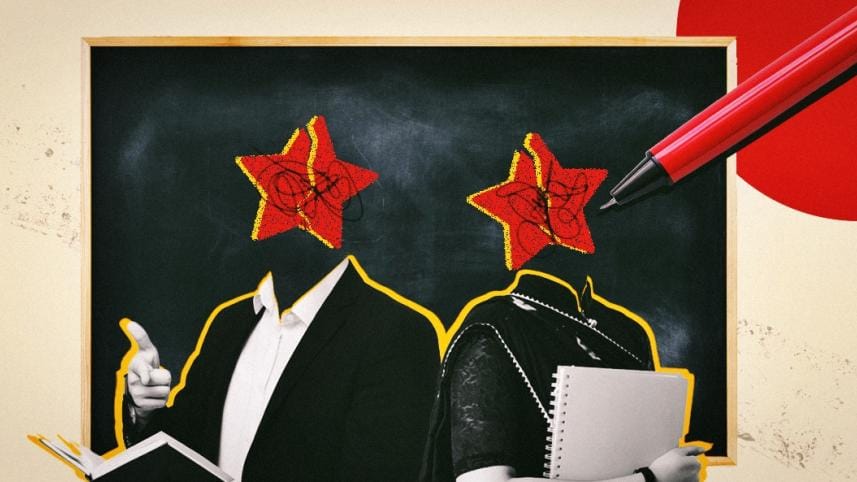

I never have the delusion of considering myself a perfect teacher. Never do I worry either that I flub teaching. I apparently have the credentials and skills to approach teaching in an informed fashion. When end-of-the-semester student evaluation of teaching comes my way, I simultaneously find myself at both ends of the spectrum—I'm either the best or the worst teacher. I know I'm none. I don't gloat over a staller evaluation. A rave evaluation doesn't upset me, either. I know students don't evaluate teachers. They rate teachers. They either like or hate teachers. Essentially, then, student evaluation of teaching is a "popularity contest" among teachers, as Beth McMurtrie claims in her essay "Teaching Evaluations Are Broken. Can They Be Fixed?" in The Chronicle of Higher Education. Research evinces that gender and racial biases contaminate this popularity contest. Consequently, student evaluation of teaching boils down to slander and scandal.

And the worst victims of such a system are our female colleagues. The American Sociological Association, for example, released a statement in 2019, reporting multiple shortcomings in student evaluation of teaching. One of their concerns was that it is biased against women, as research finds that female instructors are rated lower than their male counterparts. Worse, our female colleagues are victims of vulgarism, as they are evaluated by students. Students sometimes attempt to soil their character. They comment on their body parts at that. Their gaffes and peeves are magnified. Their dignity and identity as teachers are so compromised sometimes that they become professional pariahs. They are reduced to lesser mortals by students semester after semester. They still can't do away with such a prejudicial evaluation, because they can't find out the students demonising them. These evaluations are anonymous. Students have the right to privacy, which universities religiously protect. None, however, protects our female colleagues when they're criminally disgraced by students. Student evaluation of teaching is institutionalised misogyny.

If that's not a compelling rationale to abandon student evaluation of teaching altogether, think of the following paradox. Teaching is not a random gig randomly done by a random individual. Teaching presupposes expertise. Teaching is not a natural talent suddenly discovered. It is, instead, an ability gradually developed by means of sustained training. As well, teaching is stubbornly discipline-specific. The evaluation of teaching by students, however, presupposes no expertise. When a student evaluates a teacher, he becomes transdisciplinary and omniscient. A potential business major, for example, can sign up for basic physics, psychology, and political science courses in the same semester, and is expected to proxy for Albert Einstein, Sigmund Freud, and John Locke as he evaluates teaching. Kevin Gannon, in his essay "In Defense (Sort of) of Student Evaluations of Teaching" in The Chronicle of Higher Education, contends that students are not experts qualified to evaluate teachers. Student evaluation of teaching, therefore, gleans only clamour. It hardly says anything about the quality of instruction. Judging the teachers is not the students' business. Learning is. Learning cannot be reduced to a number, as the current evaluation metrics do. So, it's controversial.

Sceptics as such apprehend that student evaluation of teaching is a witch-hunting project, for it apparently separates popular instructors from unpopular ones. Teaching has never been a popular sport; never have teachers been performance artistes. Ideally, popularity doesn't factor into the equation of teaching. Unfortunately, however, even in 2011, Richard Arum and Josipa Roksa, in "Your So-Called Education" in The New York Times, claim that students are increasingly thought of as "clients" or "consumers." Whoever refuses to coddle them risks being unpopular. A damning evaluation with crude, aggressive, and ad hominem language follows. Students' words, especially an outlier offensive comment, are God's words. They weigh critically in merit raises, tenure, promotion, and contract renewal. Sometimes the victims are genuine scholars, who seek to touch and transform students by enlightening, disciplining, and inspiring them. And sometimes the winners are the charlatans who end up in classrooms on the coattails of the influential people they're connected with. They learn to play the game of popularity. They are ethically and intellectually evacuated, but they swagger around. If that's what student evaluation of teaching leads us to, why can't we ditch this perfunctory ritual?

Evaluation of teaching can shift from quantitative to more qualitative, as it becomes holistic when a faculty's course planning, grading policies and class management, along with gathering faculty narratives, peer observations and sample teaching materials, are evaluated.

Because these evaluations are seductively objective. They reduce teaching to a point scale. These are, then, unerring measures of good teaching. These are, instead, cheap measures, which are easy to implement in a slapdash manner. It sounds surprising that universities adhere to something so inherently problematic. What sounds more surprising is that universities are never so serious about defining good teaching as they are about evaluating good teaching. Good teaching has never been pedagogical pyrotechnics expected of a teacher, who does magical and radical things in a classroom to dazzle students. Good teaching is a gradual approach to helping students discover and actualise their potential. It's goal-driven and holistic. It's not skill-driven and specific. Students come away from a session of good teaching enlightened and inspired. No calculus captures such complex outcomes of teaching. Citing a meta-analysis, Beth McMurtrie claims in her essay in The Chronicle of Higher Education—that I already mentioned—that there is little to no correlation between how highly students rate their instructor and how well they have learnt the subject.

In fact, the correlation between high rating and good teaching is negative. Michelle Falkoff claims in "Why We Must Stop Relying on Student Ratings of Teaching," in The Chronicle of Higher Education, that professors receive lower evaluation scores if they teach challenging or difficult courses even though students succeed in later courses based on what they learnt from those professors. Likewise, reflecting on his teaching, Timothy Edwards claims in "The Inherent Unreliability of Student Evaluations," in The Chronicle of Higher Education, that the quality of his teaching improved despite having dropped his evaluation scores and that students were learning more in his courses despite their discomfort. Both anecdotal and empirical evidence suggest that students give better evaluations to professors, who grade them more generously. That reduces good evaluations to careless, unscrupulous grading. And students these days are hardly satisfied with the grades they've earned, for they always expect a better grade. They bargain. Teachers (have to) budge. What we euphemistically call student evaluation of teaching is, in fact, a "Customers Satisfaction Survey." Dissatisfied customers are angry reviewers. And they lash out at their service providers, the professors. That's unacceptable!

Nonetheless, approximately 16,000 institutions worldwide rely on student evaluation of teaching for personnel decisions, as citing various sources Richard O'Donovan claims in his article "Missing the forest for the trees: investigating factors influencing student evaluations of teaching." This is unusual, too. Universities these days operate as insular entities. They brag about how they are different from and superior to each other. When, however, it comes to student evaluation of teaching, Chicken University, South Korea, and Harvard University, US, are apparently on the same page. Such a system places total responsibility on teachers for the quality of education. Pedagogical problems are sometimes the outcomes of administrative lassitude. Student recruitment, class size and type, number of classes faculty teach per semester, and internal policies and politics of faculty management have a bearing on teaching. Because teachers serve the students directly and are evaluated by them as such, why are not chairs, deans, and other executives evaluated by faculty at least once annually, as they directly serve and supervise the faculty? Such a survey would potentially make teaching more effective, provided that the information elicited from the survey is enacted carefully.

Until that is done, the problems and paradoxes of student evaluation of teaching will continue to hector faculty. Faculty are the intellectual and financial engines of a university. They are not predatory forces pitted against students and universities. In the current evaluation system, students dis faculty, and universities use it as a cudgel against them. Consequently, universities slip into intellectual and ethical crises. Dealing with such a deplorable situation is possible. Evaluation of teaching can shift from quantitative to more qualitative, as it becomes holistic when a faculty's course planning, grading policies and class management, along with gathering faculty narratives, peer observations and sample teaching materials, are evaluated. One such model of teaching evaluation is designed by Boise State University, which they call the "Framework for Assessing Teaching Effectiveness" (FATE). The FATE framework is apparently detailed, unambiguous, and nuanced. It establishes a shared definition of effective teaching that includes four components—course design, scholarly teaching, learner-centred, and reflective teaching—each of which defines a particular aspect of teaching. There are other frameworks, too, which can be consulted to streamline student evaluation of teaching.

A critical step towards that direction is educating students on how to evaluate teaching in an informed and ethical manner, when their evaluation yet weighs marginally in determining effective teaching. Universities must also screen out comments with gender and racial biases before the evaluations are sent to faculty. Or universities might face litigation, because the current form of student evaluation of teaching is apparently ILLEGAL, as Michelle Falkoff claims in the essay I already mentioned. Who cares about the law, anyway? So, colleagues, endure!

Dr Mohammad Shamsuzzaman is associate professor at the Department of English and Modern Languages in North South University (NSU).

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments