The toll of citizen journalism in Bangladesh

In the hours following the plane crash at Milestone School and College, the internet became a theatre of anguish. Graphic images of bodies, bloodied uniforms, and weeping children circulated with merciless speed. No warning. No pause. Just as during the July Uprising and the Rana Plaza tragedy before it, social media platforms once again became unwitting archives of national trauma—unfiltered and unbearable.

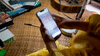

Once hailed as a democratic revolution in storytelling, citizen journalism in Bangladesh has now devolved into a spectacle. Along with the power to document and disseminate events, there now lies the power to shock, exploit, and traumatise. Armed with smartphones and fuelled by the logic of platforms like Facebook and TikTok, ordinary citizens have stepped into the role of frontline correspondents. They are often the first to capture tragedy and alert the nation. Yet the cost of this immediacy is profound. With few ethical guardrails, the boundary between witnessing and voyeurism has begun to collapse.

The equation is brutally simple: the more shocking the image, the more traction it garners. Nuanced analysis is eclipsed by visual shock. Algorithms reward outrage. Trauma becomes content.

What, then, does this steady stream of horror do to those who consume it?

Psychologists call it emotional numbing—a condition in which repeated exposure to distressing stimuli blunts our capacity to feel. When every scroll brings a new tragedy, the human psyche learns to protect itself by detaching. It is not cruelty. It is exhaustion. Empathy begins to fade.

But emotional detachment distorts our social fabric. Suffering becomes routine, injustice loses its urgency. Victims are reduced to symbols as the public becomes desensitised and power remains unchallenged. More disturbingly, this numbness begets a paradoxical craving: viewers begin to seek out more graphic, extreme, sensational content driven less by curiosity than by a subconscious desire to feel something again. In this loop, the line between witnessing and consuming is obliterated.

Compounding the problem is the rampant spread of misinformation. In the race to post first, verification is routinely cast aside. Old images are repurposed. Videos are clipped and miscaptioned. Speculation masquerades as reporting. Social media's architecture—designed for speed, not accuracy—allows falsehoods to proliferate unchecked, often with devastating consequences. This erosion of trust not only undermines journalism but also contributes to a broader epistemic crisis. In such an environment, the citizen is no longer simply uninformed; they are misinformed, manipulated, and increasingly polarised.

Young people, in particular, are navigating a digital terrain saturated with grief and gore—without the tools to make sense of it. The absence of media literacy in our education system means that students are left vulnerable to the emotional fallout of their daily scrolls. Anxiety, detachment, desensitisation—these are no longer abstract concerns.

What is needed now is reflection. We must confront the ethical responsibilities that accompany the power to document. Algorithms will not grow a conscience. The responsibility lies with us—citizens, educators, journalists, and policymakers alike. Social media platforms must be compelled to act. Content moderation must evolve beyond crude censorship into nuanced, context-sensitive gatekeeping. Graphic content should carry warnings. Age restrictions must be meaningfully enforced. Algorithms must be recalibrated to prioritise credibility over virality.

Educational institutions have a central role to play. Media literacy—the ability to discern, critique, and contextualise information—must be integrated into our curricula at all levels. Ethical storytelling should be taught not as a luxury but as a necessity in the digital age. Civil society, too, must rise to the challenge. Training in trauma-informed reporting, community workshops on digital ethics, and support structures for citizen journalists can begin to build a more compassionate media culture. Even the state, often reluctant to engage with questions of digital governance, must step forward—not through draconian control, but through public investment in mental health services, civic education, and regulatory reform.

Above all, we as individuals must ask harder questions. Before sharing an image, do we pause to consider the dignity of the person shown? Are we bearing witness, or merely feeding a machine? Is this justice, or is this consumption?

We do not need less citizen journalism. We need better citizen journalism.

Nur A Mahajabin Khan is pursuing a master's degree in environment, culture, and communication at the University of Glasgow, Scotland.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments