The politics of betrayal and trauma

Be·tray·al

: violation of a person's trust or confidence, of a moral standard, a contract, etc.

Bangladesh has experienced a dramatic series of events in recent weeks. An interim government has been formed, and we await fair and transparent elections. But we would do well to remember the cycles of betrayal and trauma that have shaped the politics of the country and to resolve that they are not repeated again.

Underlying the mass agitation that eventually led to the downfall of the previous government is a deep sense of collective betrayal. The Awami League government betrayed the most fundamental of public trusts: the expectation that the state will not wilfully kill one's children. "My son was murdered," said Shopna, the mother of slain 18-year-old protester Rahat Hossain. "And not by civilians, but by law enforcement officers under government orders. My son was killed by a bullet bought with my tax money."

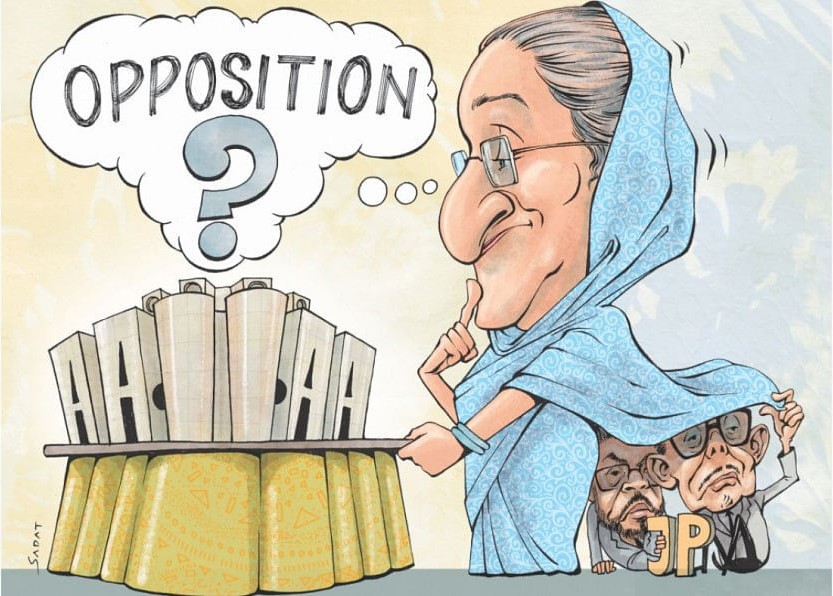

What began in early July as peaceful protests by Bangladeshi university students against the quota system in government job recruitment faced a full-scale government crackdown as the police, the military, and border guard paramilitaries were deployed to quell the unrest. An Awami League government that shamelessly clung to power for 15 years through rigged elections and persecution of the opposition unleashed its punitive might on student protesters and citizens. A curfew was declared, and internet and mobile phone networks were shut down.

Betrayal has many faces, shapes and forms. At its core, though, is the experience of violation and trauma. The psychological effects of betrayal include anger, loss and grief, self-doubt, and preoccupation or an inability to let go of the precipitating events. Human beings do not compartmentalise these feelings. Emotions seep into political cultures where they have the potential to alter the course of a society.

In the wake of the police brutality, student organisers of the quota reform movement asked then Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina to apologise for what happened. It is easier to heal after betrayal when the responsible party takes ownership for what has happened. Regrettably, the Awami League government devoted its energies to denying responsibility, to pointing fingers at everyone but themselves.

The politics of betrayal in Bangladesh is painfully familiar to me. I am the daughter of the late Shah AMS Kibria. After joining the Awami League in 1992, my father was the finance minister of the government led by Sheikh Hasina from 1996 to 2001. Following that, he was a member of the opposition in parliament and a vocal critic of the rise of militancy, persecution of religious minorities, and state-sponsored political violence in the country.

On January 27, 2005, Shah AMS Kibria was assassinated by a grenade attack during a public meeting at his constituency in Sylhet.

Following her husband's killing, the late Asma Kibria fought hard for a full and transparent investigation conducted independently of the BNP-Jamaat government of the time. I am reminded of her indomitable spirit when I hear Shamsi Ara Zaman, the mother of 27-year-old Tahir Zaman, a freelance photographer who was killed on July 17 when he went to film the protests, "I want justice. As a mother I will do whatever is necessary to get justice for my son."

When the Awami League was elected in 2009, we, the family, rejoiced. After four long years, we would get justice for my father's murder. Who more so than a government led by the political party that he had loyally served could be motivated to address the questions that had been haunting us since that fateful day in 2005? Who ordered the grenade attack on him? What was the source of the grenades?

For 15 years, the Awami League led by Sheikh Hasina has held the reins of government in Bangladesh. For 15 years, we have not seen a complete investigation and trial into our father/grandfather's murder. For 15 years, the crucial questions of motive, intent and plan remain unanswered.

It is of great sorrow to me that my mother never saw the justice that she sought. She died with the trauma of betrayal. "Where can we get justice," she said, "if even those he trusted the most do not have the will to find and punish his murderers?" Her trauma is now mine, to be passed down through the generations of our family.

Growing up, my parents instilled in me a deep appreciation for the ideals of the 1971 Liberation War and the sacrifices of those who gave their lives for the independence of Bangladesh. Over the past decade and a half, I have watched with dismay as the Awami League—the political party so closely tied with these iconic events—chose to politicise and weaponise this glorious history, using it to divide rather than unite the nation.

When I watched the terrifying footage of Abu Sayed, a student shot and killed during the quota reform protests, I felt the sting of many betrayals, one top of another and another. How could the government authorise the use of deadly force against unarmed student protesters? How could a government led by the Awami League, a party founded on principles of self-determination and democracy, turn on its own people? There is a sense in which I am grateful that my father is not around to see the moral degeneration of the party he served with dedication.

Bangladesh is now at a political crossroads. The country, I believe, can only heal from the trauma of betrayal if there is a concerted building of trust in public institutions and those who serve in them—whether it is a policeperson directing traffic or a clerk at the passport control office or a Supreme Court judge. The politicisation of our institutions must stop. After all, in the end, it is very easy to be betrayed by a political party or a political leader. But if we know that our public institutions are there to serve all of us, regardless of who is in power, it may not matter so much.

After all, as Shah AMS Kibria used to say, "We Bangalees can never be put down for long. We sacrificed our lives for freedom once and we will do so again if necessary."

Nazli Kibria is professor and interim chair of sociology at Boston University.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments