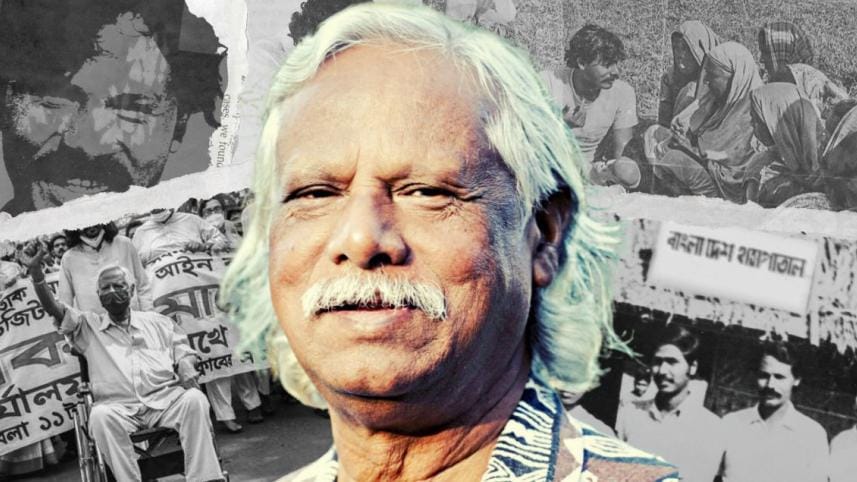

The man who walked the talk

As a student in the 60s, Zafrullah Chowdhury did not mince his words while exposing the Dhaka Medical College's incessant corruption to the media. Neither did he think twice before leaving the comforts of a British education, returning to fight for his nation's emancipation in 1971.

Beyond armed struggle, he set up field healthcare services for freedom fighters – instrumental in supporting the war effort against the Pakistani military junta. Bangladesh was born, and Chowdhury was a silent, but game-changing figure in defining the country's inception and its sovereign landscape.

Under Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib's patronage, Chowdhury established the pioneering Gonoshasthya Kendra – a symbol of the highest ethical ideals in healthcare provision. In the late 70s, General Ziaur Rahman attempted to persuade Chowdhury to join his Cabinet. Always a man who put principles above everything else, he refused – and drafted a now famous four-page letter to the president, citing that he would not join a government which comprised of anti-liberation forces.

After General Ershad took over the reins, Chowdhury worked towards formulating Bangladesh's National Drug Policy. Today, the country is seen as a global leader in the pharmaceutical industry – and Chowdhury is undeniably its principal architect.

While Chowdhury lambasted BNP for celebrating their chairperson's birthday on August 15th and condemned the culture of impunity following the August 2004 grenade attacks, he remained a fierce and loyal adviser to Khaleda Zia – who trusted him to her core. In recent years, he denounced the anti-democratic proclivities of the current regime, and did so by reminding the Awami League that they had forgotten their pro-people roots.

In his last act, a visibly frail Chowdhury attended a reception at Bangabhaban a few weeks ago. He pleaded to Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina to engage in dialogue with her opponents prior to the elections. In a nutshell, Chowdhury was the antithesis of the traditional Bangladeshi political operative, whom the younger generation have learnt to vehemently dislike. He understood, better than anyone, that politics is not simply about power – but an avenue to serve the people.

He was candid and blunt and held strong to his opinions. But he also recognised that those opinions may differ from that of others and saw it as a good thing. He did not pay heed to who was in power. He advised from his heart, and had the courage to do so by speaking the truth. Owing to this, he earned the respect of all political actors. In today's Bangladesh, this is not simply an anomaly – but a utopian dream.

In a nutshell, Chowdhury was the antithesis of the traditional Bangladeshi political operative, whom the younger generation have learnt to vehemently dislike. He understood, better than anyone, that politics is not simply about power – but an avenue to serve the people.

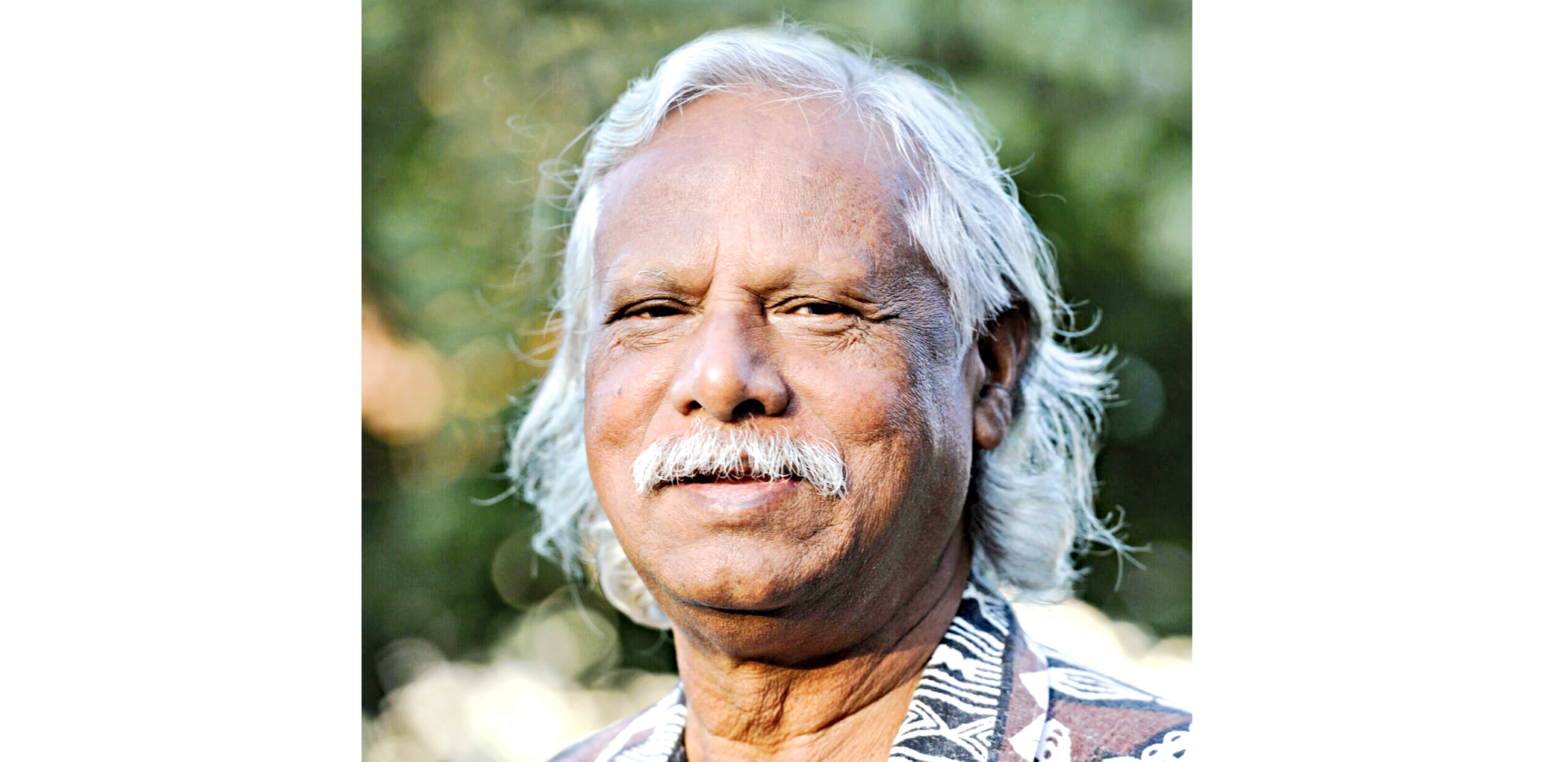

Dr Zafrullah Chowdhury's legacy is multifaceted and far-reaching, encompassing his contributions to healthcare, education, human rights, and governance. Gonoshasthaya Kendra, the community-based healthcare organisation that provides affordable and high-quality medical services to millions of people, especially in rural areas, will remain a living testament to his legacy. His innovative and inclusive approach to healthcare, which emphasises the importance of preventive medicine, patient empowerment, and community participation, has been hailed as a model for other developing countries.

As a physician himself, he understood the typology of health care and worked diligently to transform an amorphous and monolithic system into one that was accessible to all. His efforts in increasing the visibility of health services, incorporating women in the sector, and making healthcare affordable for the average citizen has been nothing short of revolutionary.

Beyond his profession, his commitment to social justice and human rights was equally impressive. He has been, throughout his life, a vocal critic of authoritarian trends and a fierce advocate for democratic reforms, free speech, and the rule of law – while being cognisant that he had an obligation to work with all political parties, to serve the people of Bangladesh.

Perhaps what sets Chowdhury's legacy apart from others is his ability to work across political and social divides. He was a rare example, in fact the only person that comes to mind, of a figure who could command the respect of both the ruling party and the opposition, and who was willing to engage in constructive dialogue with his opponents. His ability to transcend partisan politics and focus on the bigger picture was a demonstration of his vision, leadership, and moral courage.

He knew that frivolous arguments and mendacity would only serve to derail the country's development – and he refused to let such malfeasance get in the way of his mission to serve the people. Throughout his career, Chowdhury was a firm believer in the interaction between dialogue and division, understanding that it is only through respectful discourse that we can move forward as a society. This genesis of his approach was evident in his ability to work with every government since independence.

Today, as we mourn his loss, we must also celebrate his legacy. He has shown us that politics need not be a dirty word, that healthcare is a right, not a privilege, and that dialogue and respect can take us further than we ever thought possible. Let us pay tribute to this great man by carrying forward his vision for a better Bangladesh, one where the interplay of ideas and the spirit of cooperation reign supreme.

If you are someone who dislikes today's brand of politics and have distanced yourself from public life, look towards Zafrullah Chowdhury for inspiration. Bangladeshi governments have an unfortunate habit of glorifying leaders who only represent their respective political parties. One hopes Chowdhury gets the posthumous recognition he deserves from the state. If there was a list of the greatest Bangladeshis of all time, his name should be in the reckoning. He has won the highest state honours and multiple international awards – but more importantly, he has captivated the nation via public service.

To Zafrullah Chowdhury: We thank you. Yours is a life well lived. And you were, in the truest sense, a quintessential public servant who lived and breathed not for yourself, but for those whom you served.

Aftab Ahmed is a Master of Public Policy candidate with the Max Bell School of Public Policy at McGill University. He is a regular columnist for The Daily Star and Dhaka Tribune and can be reached at aftab.ahmed@alum.utoronto.ca

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments