The injustice of our inflation is tilted against the poor

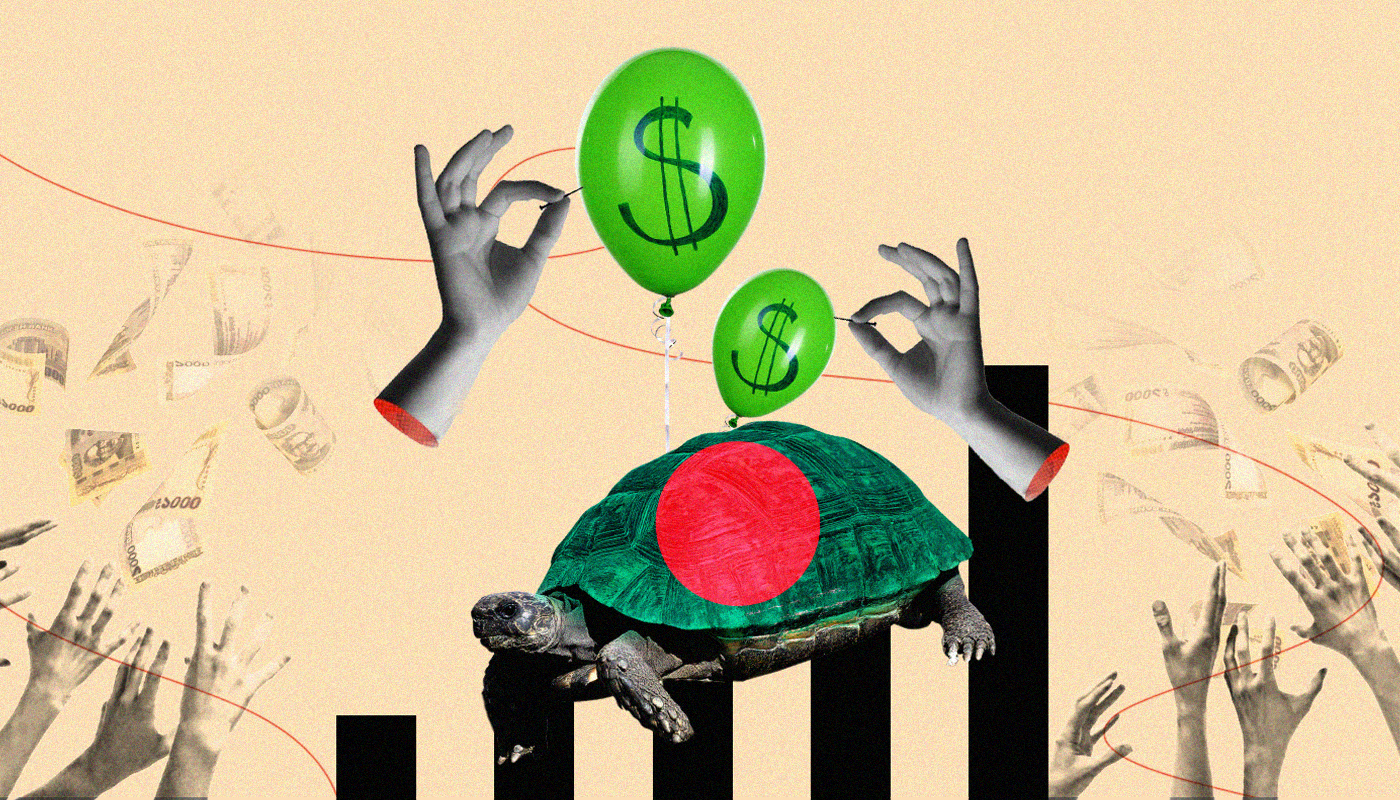

The way inflation works in our economy is profoundly unjust. Prices are rising in ways that mirror a deeper imbalance in our social and moral order—a widening gulf between capital and labour, between those who set prices and those who must bear them. It reflects how our institutions, intended to protect fairness, bow under the weight of capture and complacency. It reflects an economy whose intent and design have grown inequitable.

The injustice of our inflation lies in its asymmetry. As in most capitalist societies, those who control capital or trade in scarcity are shielded, even rewarded, while those who work with their hands and hearts are quietly impoverished.

In towns and cities alike, this story plays out in an unending loop. Most vegetables in the market would eat away half of a day labourer's daily income. Meanwhile, sources of protein such as fish have become a luxury for many families and meat—a distant memory. Most treat lentils as a substitute for meat.

The Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) confirms that prices have risen faster than wages for more than three consecutive years. September marked the 44th consecutive month in which wage growth failed to keep pace with inflation. Nominal incomes rose by about eight percent between August and September, but prices rose by more—progress has become loss disguised as gain. Although inflation has somewhat eased since last year, the gap between inflation and wage growth remains tenacious. At first glance, the gap may seem minor; in reality, it is the difference between treading water and drowning, between a family eating twice a day or only once.

This imbalance is most visible not in data but in the stories of those who produce our food. The prices of rice, potatoes, and onions have surged, yet farmers often sell these crops at a loss. In Gaibandha, we met farmers who spoke of potatoes and betel leaf left to rot even as consumer prices climbed. A Bangladesh Bank study found that even when harvests are strong, supply-chain bottlenecks and intermediary mark-ups drive up retail prices in the markets, where farmers sell below production cost, which results in the final consumers paying many times more by the next day. The rewards of rising prices flow upwards; the risks stay below. Farmers take the losses, consumers pay the costs, and those who control storage, transport, and trade capture the rent in between. Inflation here is not demand-pull or cost-push; it is rent-pull, born of power asymmetry rather than productivity.

Our repeated money-whitening schemes stand as unabashed monuments to this injustice—government amnesties that in the past have allowed untaxed wealth to be legalised through real estate or stock investment. These pragmatic tools "bring hidden money into the economy" at the cost of widening the gap between the privileged and the rule-abiding. When a garment worker's real wages fall by two percent and their meagre savings are eroded by inflation, while a wealthy investor can whiten crores of taka at a flat tax, the social and moral contract underpinning our economy begins to collapse.

It is easy to blame global events: the war in Ukraine, fuel shocks, the weakening taka. These factors played a role, but they are no longer the primary driver. The currency's persistent depreciation is, of course, an ongoing source of imported inflation, raising the cost of fuel, fertiliser, and industrial inputs. Yet, macro pressures alone cannot explain why prices remain high long after global costs have eased. In truth, macro instability and domestic rent-seeking now feed each other—the weakening taka gives cartels cover to keep prices inflated, and those inflated prices, in turn, deepen fiscal pressure and erode confidence in the currency. It is a toxic coupling, one that thrives because governance fails to separate real cost-push from opportunistic greed.

For too long, perhaps forever, we have treated inflation as a technical matter to be managed rather than a moral question to be answered. Inflation reveals who a nation protects when scarcity arrives, and for 44 months and counting, Bangladesh has been failing that test. The poor are paying for inflation twice: once at the market and again in lost trust that the system was ever meant for them.

Restoring balance will take more than technocratic fixes. The syndicates are not abstract market failures; they are extensions of power itself. To challenge them demands not only courage but independence: regulators insulated from politics, and a free media that insists on accountability. Without that separation, every promise of reform collapses under its own conflict of interest.

Inflation is not just a measure of prices; it is a measure of priorities. It tells us whose pain we deem tolerable, and whose creature comforts we protect. Each queue at an OMS truck, each unpaid overtime shift, each farmer's unsold harvest is another reminder of how ordinary struggle has become our national condition. With political courage, institutional integrity, and moral clarity, we can build an economy where prices rise for reasons of growth, dictated by the market, not by greed.

The injustice of our inflation is not inevitable. We are the root cause, and therefore, it can be undone.

Saba El Kabir is a development practitioner and founder of Cultivera Limited. He can be reached at saba@cultivera.net.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries, and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments