The cost of leaving home

Arif left Dhaka last year for what he called "a better life." On paper, he's thriving: a stable job in IT, a modest flat in Manchester, a new fondness for waterproof jackets. But when I asked him what he missed most, he didn't just say "lazy mornings," "adda over chaa," or "my mother's voice." He mentioned, "having someone to laugh with at 2am without booking it on Google Calendar."

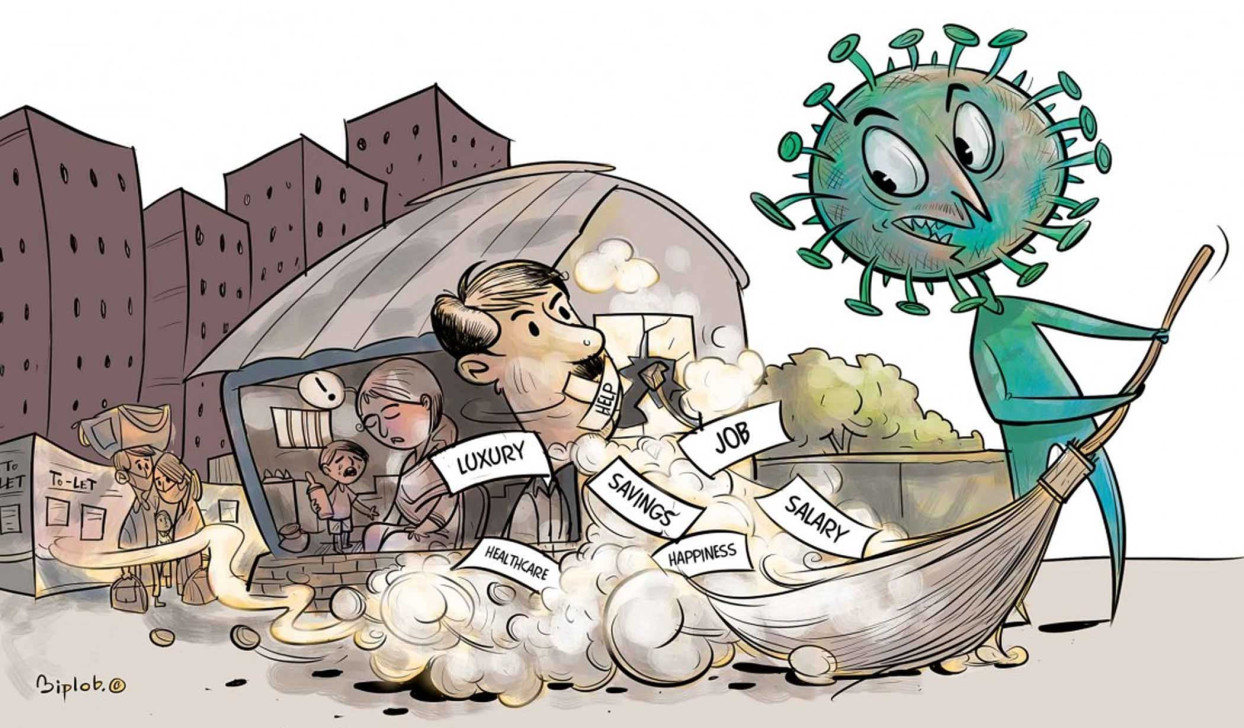

This is the unspoken cost of leaving—the everyday moments that don't fit into migration agency brochures or glossy remittance statistics. Every year, thousands of young Bangladeshis chase foreign horizons. They leave with suitcases stuffed with pickles, dry fish, and dreams, imagining a land paved with career opportunities and better healthcare systems. And yes, the paycheques are bigger, the streets are cleaner, and no one honks when the traffic light turns green. But no one tells you that in exchange for your pounds and dollars, you must mortgage your roots, your community, and sometimes, your sanity.

The first year abroad is often a blur of survival. You're figuring out buses, signing tenancy agreements, and learning how to cook dal without it resembling uptan. You post triumphant photos on Instagram—new jackets, neat flats, foreign skylines—because admitting you cried into a frozen paratha from a supermarket doesn't fit the narrative of success. Back home, your family beams with pride as they whisper to neighbours about "amader chele UK te ase." What they don't see is their son walking home from work through a city of strangers, the silence broken only by the squeak of his shoes.

Across oceans and time zones, the promise of greener pastures often ends with patchy Wi-Fi calls where mothers pretend not to cry and fathers say, "Don't worry about us, you just take care of yourself."

The festivals hurt most. Eid, which once meant noisy cousins, chaotic kitchens, and new clothes, becomes an awkward Zoom background. Abroad, you microwave frozen samosas, slip into your one neatly ironed panjabi, and send digital salamis. The only "Eid crowd" you face is the queue at the halal butcher. It is festive enough for Facebook posts but hollow enough to make you long for the sweaty, noisy, joyful chaos of Dhaka mornings, where 30 relatives fought over who got the leg piece of the roast.

Weddings aren't spared either. Back home, they're three-day-long circuses of colour, gossip, and gluttony. Abroad, you scroll through grainy livestreams on Facebook, hearts breaking as you spot your childhood best friend dancing without you, your favourite auntie crying at her daughter's farewell. You send a congratulatory message with emojis, but deep down you know: emojis cannot hug, and live streams cannot smell of roses and kacchi biryani.

Even ordinary days are filled with absence. No cousin showing up with shingara on a rainy afternoon. No uncle popping by to argue politics over cha. No rooftop cricket games at sunset, no neighbourhood shopkeeper who already knows your brand of chanachur. Abroad, you are anonymous—another brown face in a sea of commuters, another "Arif" mispronounced as "A-reef." You gain privacy but lose belonging.

And then there are the parents. They age faster in your absence. They pause longer before answering the phone. They skip details about illnesses because they don't want to worry you. You send them money; they send you blessings. Then both sides cry after pressing the red button. In a cruel twist, the very remittances that build bigger houses in Baridhara also build emptier ones, because the children they were meant for live half a world away.

Communities back home feel the loss too. Every farewell party is disguised as a "get-together," with Dhaka increasingly seen as a layover, not a destination. Neighbourhood football teams vanish, rooftops grow quieter, and even weddings lack the warmth they once had. A society can lose more than its workforce; it can lose its laughter, its culture, its collective memory.

None of this is to say staying behind is easy. Bangladesh tests patience in ways no IELTS preparation class ever could. There are traffic jams that feel like psychological warfare, low salaries that make ambition look like a luxury, and politics that would make Machiavelli throw up his hands. It's tempting to leave, and many do. But leaving carries a price tag that no exchange rate can balance: fractured families, eroded traditions, and the slow hollowing out of community life.

Because yes, you can build a house with your pounds, but who will sit in it with you when you come back? You can pay your parents' hospital bills, but will you be there to hold their hands in the waiting room? You can buy your child Lego sets from London, but will they ever know the joy of catching fish in monsoon floods with cousins?

Home is not just geography. It is shared memory, messy togetherness, and the comfort of being known. When we trade that for Western salaries, we gain financial stability but lose something harder to measure: belonging. In the end, I think the question is not just how much we gain by leaving, but how much we lose by not staying. And that loss may be the heaviest price of all.

Barrister Noshin Nawal is a columnist for The Daily Star. She can be reached at nawalnoshin1@gmail.com.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments