Taming Inflation: Let the orthodox monetary policy work

Bangladesh has been experiencing rising inflationary pressure for at least 18 months. In fact, monthly inflation reached as high as 9.94 percent in May 2023 and still remains stubbornly high at 9.67 percent in February 2024. Uncontrolled inflationary pressure is one of the most problematic phenomena in the country. Lessons from economic history vividly demonstrate that high inflation can hinder macroeconomic stability, erode competitiveness of local entrepreneurs, demotivate investment decisions, and accentuate income inequality by substantially reducing the purchasing power of fixed-income and financially weak households.

Thus, it is not surprising that mature monetary regimes across advanced economies commit to an inflation targeting framework where the primary agenda is to keep inflation at about two percent annually. This also explains why, recently, central banks across advanced economies have responded aggressively to tighten money supply and raise interest rates, which translated into lowering inflationary pressure in their respective economies. Interestingly, this also creates a useful context for evaluating the effectiveness of our monetary policy, which has largely been ineffective in controlling inflation.

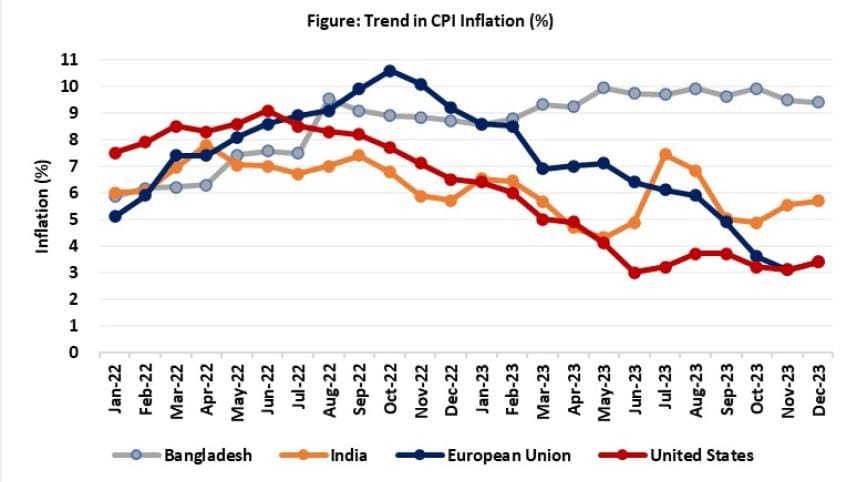

More simply, given that global inflation has been coming down over the last 18 months, why has inflation in Bangladesh maintained an upward trend since mid-2022? In other words, why is inflation in countries like India and Sri Lanka less than six percent while it remains above 9.6 percent in Bangladesh? What explains this divergence?

To decode this heterogeneity in monetary performance, this analysis will offer insights on three core issues: (i) the set of factors that has driven the global inflationary pressure and how it has been addressed by central banks across the world. In particular, we try to distil the broad lessons that emerge from the international experience; (ii) the set of factors that has driven the inflationary pressure in Bangladesh, and why Bangladesh Bank has failed to tame the inflationary pressure; and (iii) the exact policy decisions that might help bring the current inflationary pressure under control.

Drivers of global inflation and lessons for monetary policy

There is now a consensus among experts that excessive fiscal and monetary stimulus in response to Covid, along with the supply chain disruptions stemming from the aftershocks of the pandemic and Russia-Ukraine war, fuelled this spike in inflation across countries. The initial expectation that the inflationary spike is a transient phenomenon did not come true, and advanced economies started preparing for the worst-case scenario—stagflation—where it was expected that inflation and unemployment rate would rise and remain high simultaneously. This prompted central banks in advanced countries to raise their respective interest rates and commit to contractionary monetary policies, given from the standpoint of macroeconomic management; inflation is seen as a more dangerous problem than unemployment.

For instance, inflation in the United States reached as high as 9.1 percent in June 2022—the highest in 40 years. Responding to this growing crisis, the Fed increased its policy rate eleven times to a range of 5.25 to 5.5 percent—the highest policy rate in 23 years. Consequently, inflation since then decreased substantially, coming down to 3.1 percent in January 2024. Even in India, over the same time span, inflation came down from 7.7 percent to 5.1 percent—responding to the Reserve Bank of India's (RBI) decision to increase the policy rate to 6.5 percent. A similar phenomenon was also observed for the European Union where a contractionary monetary policy brought down inflation from 11.50 percent in October 2022 to 3.1 percent in January 2024.

It is also interesting to underscore that in the US, EU and India, inflation management through contractionary monetary policies did not result in any serious spike in unemployment or nosedive in economic growth. The noted regions have achieved an economic "soft landing," a phenomenon that has pleasantly surprised policymakers who expected costly growth implications of a sustained contractionary monetary policy stance.

Of course, not every nation-state crafted a similar response for inflation management. Türkiye boldly and quite foolishly did what no one expected: its central bank, under pressure from President Tayyip Erdogan, decided to lower interest rates despite an inflation rate of 20 percent, arguing that such measures would help increase investments and smoothen supply-side constraints. But this unorthodox monetary policy experiment did not work and inflation increased to 80 percent in 2022. Subsequently, Türkiye has corrected its earlier devastating monetary policy blunder by increasing its interest rate to 40 percent, which has triggered a downward trend in its inflation rate (standing currently at 65 percent).

On the whole, the global downward trend in inflation validated the effectiveness of an orthodox monetary policy, which views inflation as a largely monetary phenomenon and supports inflation management through contractionary monetary policy stance.

Drivers of inflation in Bangladesh and BB response

As the inflationary pressure in Bangladesh remains sturdy, it is essential to pinpoint its possible drivers. According to the latest monetary policy statement published by the Bangladesh Bank, our inflationary pressure is fuelled by three key factors: (i) supply chain disruptions stemming from post-Covid demand spike and Ukraine-Russian war; (ii) exchange rate depreciation due to higher import bills in FY2022 (which could have been due to money laundering through over-invoicing of imports); and (iii) a sharp energy prices adjustments after the Ukraine-Russia war.

This we believe is an accurate but an incomplete assessment as it ignores a number of key additional issues that have seriously compromised the authorities' efforts to contain inflation. These are: (i) keeping the interest rate structure administratively fixed in the range of six to nine percent for a long time, ignoring the global developments and the post-Covid surge in domestic inflation; (ii) keeping the exchange rate virtually fixed against the US dollar for almost 12 years, contributing to a massive balance-of-payment imbalance and a sharp depreciation of the taka; (iii) injection of substantial monetary stimulus to navigate the economic effects of Covid, which was necessary at that time but was not sterilised subsequently; (iv) printing of high-powered money by the Bangladesh Bank for lending to the government to compensate for revenue shortfall in FY2023; and (v) injection of emergency funds through promissory notes into troubled Islamic banks in December 2022 and December 2023, partially offsetting the efficacy of the central bank's contractionary monetary policy stance. Collectively, these issues need serious recognition in policy formulation.

It is also essential to underscore that the Bangladesh Bank's initial narrative that the inflation was transitory due to external supply shocks and would unwind with supply situation improving was wrong. Thus, its earlier reluctance to remove the six to nine percent interest rate band undermined its fight against inflation. The unchanged interest rate policy also widened the interest rate differential in favour of the US dollar, thereby undermining the authorities' efforts to limit the depreciation of taka by making the taka less attractive against the dollar. The unfavourable return on taka assets coupled with the exchange rate depreciation turned the financial account of the balance of payments significantly negative for the first time in many decades, accentuating pressure on foreign exchange reserves and the exchange rate as short-term capital inflows dried up. Since up to 40 percent of inflation could be attributed to the 30-35 percent depreciation of the taka, an aggressive interest rate policy could have a dampening impact on the inflationary pressure.

Going forward, it is encouraging to note that Bangladesh Bank has moved away from its earlier narrative and has announced the adoption of a tighter monetary stance in its latest Monetary Policy Statement. The authorities have already abandoned the six to nine percent interest policy band, have announced that there would be no recourse to central bank borrowing for budget financing, and the resulting bank financing of the budget deficit has contributed to a significant increase in the interest rates on treasury bills and bonds.

The green shoots of macroeconomic stabilisation is already visible in the form of: (i) external current account being in surplus due to import compression; (ii) stabilisation of the official foreign exchange reserves at around $18-20 billion level; (iii) an apparent stabilisation of the exchange rate around Tk 120-124 per dollar for the last three months; and (iv) an upgradation of the outlook for the banking sector by Moody's due to increased profitability, some recovery in bank deposits and improved liquidity situation, all resulting from the abandoning of the fixed interest rate band.

Given the gains already visible, the Bangladesh Bank needs to go further to consolidate the gains. The post-election hike in the policy rate by 25 basis points was too little too late. The policy rate should be increased in steps of 50 basis points per month for the next four months before considering a pause in the policy rate increase. The basic principle should be to "continue increasing the interest rate until the inflation rate comes down close to the target range." We are still very far from that.

The agenda for restoring macroeconomic stability including price stability—in addition to interest rate hikes—will require (i) unification of the exchange rate in the interbank market; (ii) a sizable cut in non-essential fiscal spending (which we believe is underway); and (iii) refraining from central bank financing of the budget deficit despite the expected pickup in budgetary spending in the final quarter of FY2024. Notwithstanding the initial hesitations and delays, the authorities' current policies are in the right direction and working. What is needed is to strengthen the orthodox policy measures further along the lines described above, and allow for six to nine months of time for the policies to deliver the desired results.

Dr Ahsan H Mansur and Dr Ashikur Rahman are executive director and senior economist, respectively, at the Policy Research Institute (PRI). They can be reached at ashrahman83@gmail.com

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments