Taking care of our elderly must not be an afterthought

I met Sagarika (pseudonym) a couple of years back in a remote corner of Bangladesh while collecting data for my research. She was a widow in her late 70s, living in an abandoned building. Her two sons deserted her and migrated somewhere else – she didn't know where. She lost her home to river erosion 10 years ago. Since then, she had been squatting in that building.

The building was not at all suitable for any human being to live in. When I found her, she was nearly starving. The previous few days, she had survived only on muri, which she borrowed from a neighbour. Occasionally, she went begging. Whenever she felt sick, she went to the nearest local pharmacy to ask for free medicines. Sometimes it worked, sometimes it didn't. For unknown reasons, people called her pagli. That's what her identity is now in the community. You won't find Sagarika by her name; rather you have to look for a person named pagli. Despite the fact that she feels demeaned by this name, she always reacts with a smile. It's an involuntary and self-negotiated smile. She is sure that the cost of resistance will be higher for her. Despite being eligible, she is neither getting the old age allowance, nor the widow allowance. "What do you need the most now?" I asked her during our discussion. The answer I expected was "food." To my surprise, despite the visible symptoms of being malnourished and suffering starvation, she replied, "Son, I need a kerosene lamp."

For the last 10 years, she couldn't light her room when it went dark because she couldn't afford to buy kerosene. After dusk, the abandoned building becomes a shelter for cats, dogs, insects and other animals. And she is afraid of living with them at night. "Do you have a dream?" I asked her. "How will I die and who will perform my funeral rites always keep haunting me," she responded. "What else do you need?" I asked further. "Do you think a dead person needs anything?" she replied.

As I was completing my fieldwork, the responses became familiar to me. Many of the elderly individuals I interviewed said that people called them mora (corpse). It sounds very insensitive, doesn't it? But when elderly people like Sagarika are deserted by their families, neglected, and treated inhumanly by society, and ignored or prioritised less by the state and its institutions, it is nothing more than a living death. Human beings need a basic structure to survive. Dignity is a core pillar of it, which is badly missing in these elderly people's lives.

I can share many more stories from my fieldwork, but Sagarika's case is a typical one, representing those who are ageing in extreme poverty, marginalisation, and destitution. Such stories raise several burning but unanswered questions: who is in fact responsible for the elderly persons? We assume they are under the care of the family system, but are they really being cared for? When we live in a society where we do not even enjoy our dignity during our lifetime, can we even dream of a dignified death? Do we understand the concerns and needs of the elderly citizens of our country? How much do our policies and programmes cater to their needs? I doubt we have any suitable answers to these questions.

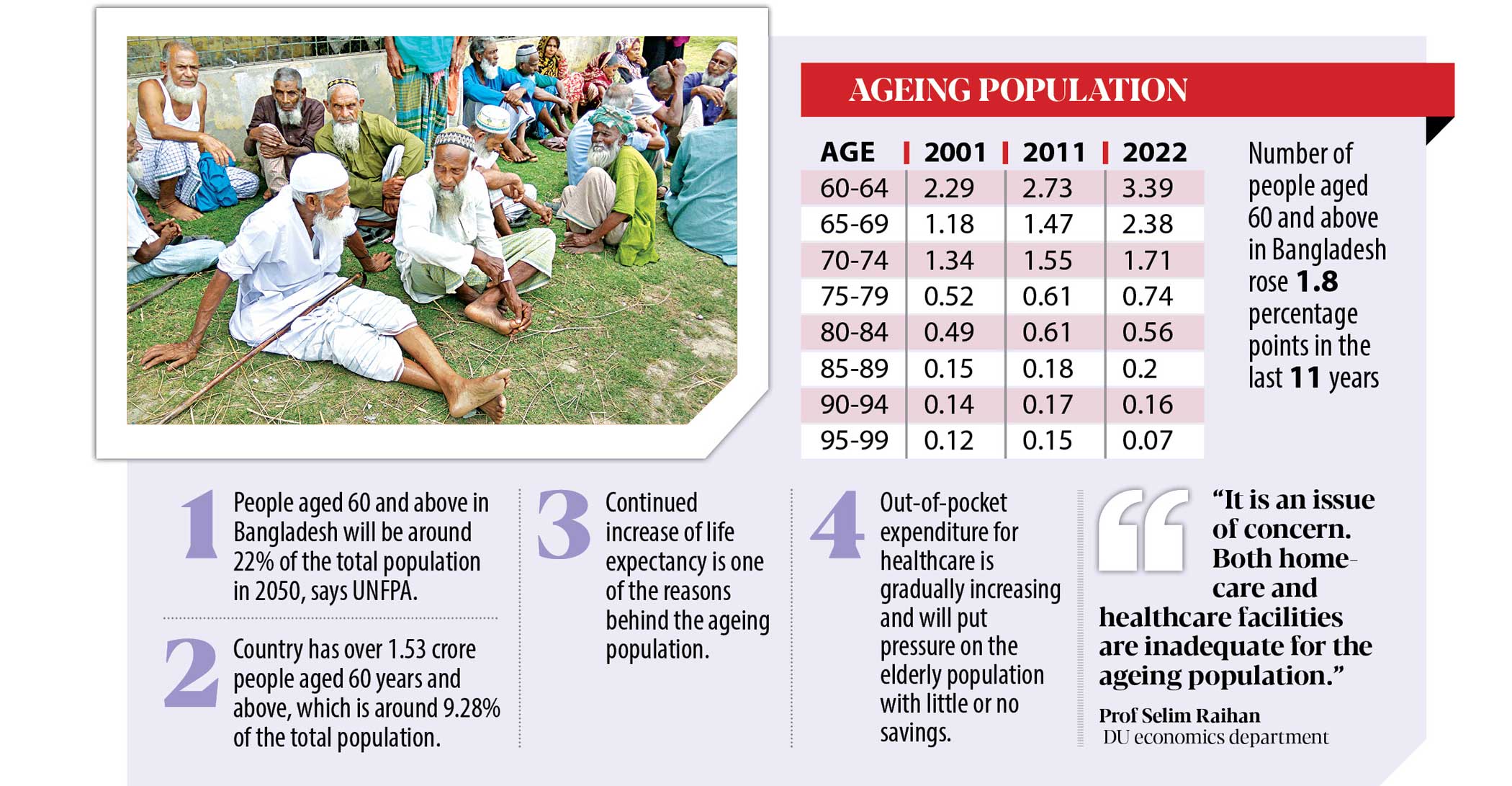

Bangladesh has been experiencing sustained economic growth, leading to its graduation to a middle-income country. Yet, Bangladesh is one of the top five countries that host half of the world's extreme poor. Its population is also ageing faster. According to the recent population census, the country now has a population of more than 15 million who are above the age of 60. According to the United Nations, this is projected to be 21 million by 2030 and 42 million by 2050. Yet, it is barely brought up in political and other discourses. We have very little research available on their living conditions, but sporadic research suggests around 43 percent of elderly people are poor and 28.2 percent of them live below the poverty line.

There is a strong presence of a wide range of development actors across the country. However, ageing is neither a priority of the development agencies nor are they considered the primary target groups. An intergenerational approach to development may yield more without requiring additional investment. We also need to initiate intergenerational programmes widely so that we understand and recognise the value of each other while nurturing our nearly lost social norms and values.

While the traditional support structures are increasingly malfunctioning in terms of offering care and protection to the elderly in our society with dignity, a lack of concerted effort is promoting a negative attitude towards them. Existing ageing-related policies and acts still assume that their families would provide for them. This is unrealistic in the sense that our family system itself is going through a transition. Poverty, unemployment, inequitable access to resources and opportunities are heightening inter and intragenerational tensions and conflicts. Bangladesh is thus in need of strong family policies that are sensitive to the needs and concerns of different generations. The family must remain at the epicentre of those policies.

There is a saying that a society is measured by how it cares for its elderly population. Aside from the story of Sagarika, we have seen plenty of examples of how our society treated its elderly citizens during the pandemic. It is high time we started to plan and invest into the well-being of our ageing population.

Owasim Akram is a doctoral researcher at Orebro University, Sweden.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments