In search of a new political language

The student-public uprising of July-August 2024 in Bangladesh, which culminated in the ousting of Sheikh Hasina's authoritarian government, defies the conventional narratives surrounding democratic movements. Unlike classic political revolutions, this uprising did not forge a new collective language centered on ideals like democracy or pluralism. Instead, it was propelled by a singular and organically emerging objective: removing an increasingly authoritarian regime. The movement's success hinged not on a visionary articulation of a shared future but on a pragmatic alignment of political, social, and civic forces around a common goal.

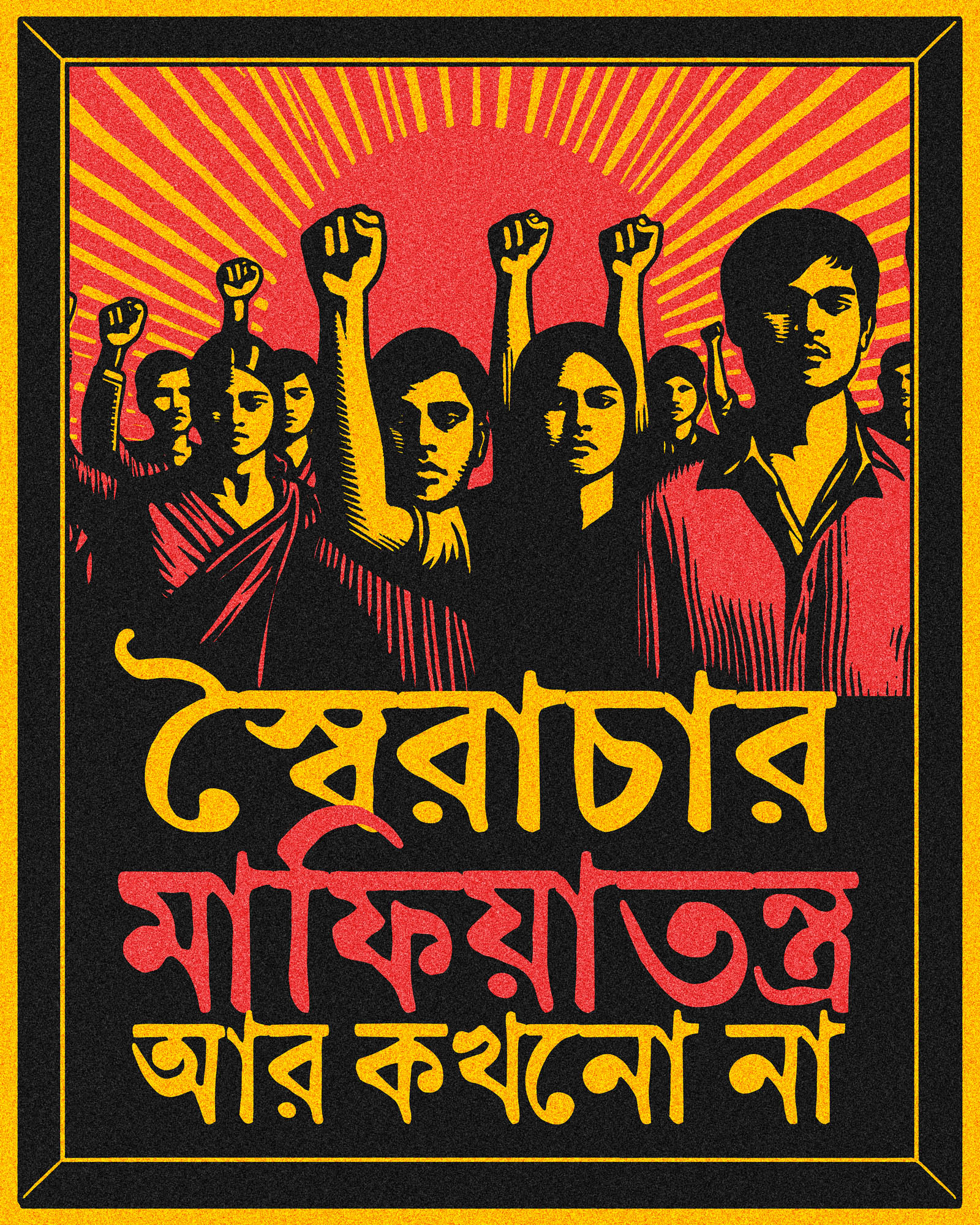

For years, Bangladesh's political landscape had been dominated by the toxic binaries of "pro-Liberation" versus "anti-Liberation" forces, a narrative deftly deployed by the ruling Awami League to marginalise opposition parties. The anti-discrimination student movement that spearheaded this summer's protests managed to challenge and neutralise this binary opposition. Their slogan, "Who are you? Who am I? Razakar! Razakar! Who said so? Who said so? Dictator! Dictator!"—with 'razakars' referring to collaborators with the Pakistani army during the 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War—served as a powerful tool to dismantle the Awami League's divisive rhetoric. This seemingly simple yet powerful slogan created a rare public space where individuals from various political backgrounds, including those previously silenced or stigmatised, could voice their grievances.

Yet, despite this, it would be a mistake to overemphasise the role of language or slogans in the success of the uprising. The real driver of the movement was bound by the urgent, shared goal of toppling an oppressive regime that had, for over a decade and a half, used state power to repress political dissent, co-opt civil society, and silence opposition. The deaths of more than 400 Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) activists during the protests signalled the high stakes of the movement, but their involvement was notably subdued. Their participation was largely concealed under the broader banner of student-led protests.

This raises a critical question: why did the student-public uprising succeed where established political parties like the BNP failed, despite their shared goal of regime change? The answer lies in a deep-seated political distrust that had taken root among the Bangladeshi public. For years, parties like the BNP had struggled to build movements capable of galvanising widespread support. Their language of democracy and pluralism rang hollow in a society that had become disillusioned with the very notion of political integrity. The public's willingness to engage with traditional parties had been eroded by decades of political corruption, entrenched narratives of division, and the government's effective use of the 'development' discourse to mask civic disenfranchisement.

The student movement, in contrast, benefited from its lack of established political identity. It was not weighed down by a history of electoral losses, internal corruption, or failed attempts at coalition-building. By leading a protest against discrimination in government recruitment—an issue that resonated deeply with young people frustrated by the lack of opportunities—the students managed to unify disparate groups. The movement's strength was its ability to articulate the public's growing discontent with an authoritarian regime that had long disrespected its citizens, masked by claims of national development.

The fall of Sheikh Hasina's government was the ultimate, if unspoken, objective that united both political actors and non-political participants in the movement. While the initial demands focused on reforming the civil service quota system, the government's brutal response to peaceful protests quickly expanded the movement's scope to shift focus from from social reform to outright regime change. By early August, the call for Sheikh Hasina's resignation had become the movement's de facto singular objective, even though this demand was formally declared only weeks after the protests began.

Rather than a shared aspiration for democracy or pluralism, the movement's true collective language was the common desire to end authoritarian rule. It was not a vision of a future democratic state that unified protesters; it was a rejection of the present authoritarian regime and the repressive tactics it employed.

Ironically, the student movement's success in crafting a public space where diverse political actors could rally under a common banner also sowed the seeds of future divisions. Without a shared understanding of what should follow Sheikh Hasina's removal, ideological divisions re-emerged and triggered internal conflicts within the movement. This is not unusual in movements focused primarily on opposition to a common enemy rather than a shared vision of governance.

The post-uprising disunity highlights an essential truth about political revolutions: the language that unites a movement in opposition is often insufficient to sustain it in power. The lack of a deeper, collective vision for Bangladesh's future beyond the remarkable fall of Sheikh Hasina reflects the fact that the student movement, despite its success, did not generate a new political language for the country.

After Sheikh Hasina's ouster, Bangladesh faces a critical juncture: developing an inclusive political language to tackle corruption, civic disenfranchisement, and social inequality. While the student movement toppled the regime, it did not—and perhaps could not—lay the foundation for a democratic future, which requires a broader reimagining of the political landscape.

In sum, the July-August 2024 uprising in Bangladesh shows that a clear and simple goal—removing an authoritarian regime—can unite diverse actors, but the real challenge ahead is building a sustainable and inclusive political future, for which the country still seeks its collective language.

Dr Kazi ASM Nurul Huda is associate professor of philosophy at the University of Dhaka. He can be reached at huda@du.ac.bd.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments