Saudi-Pakistan pact redraws strategic lines in a shifting region

A smiling Pakistani Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif, greeted with Saudi F-15 flyovers, a ceremonial red carpet and full royal honours, stood alongside Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman last week to endorse a new Strategic Mutual Defence Agreement (SMDA). The optics were striking: two long-time allies formalising what officials called a "shared deterrence" framework. What was once a loose partnership rooted in history is now given a binding clause: an attack on one shall be treated as an attack on both.

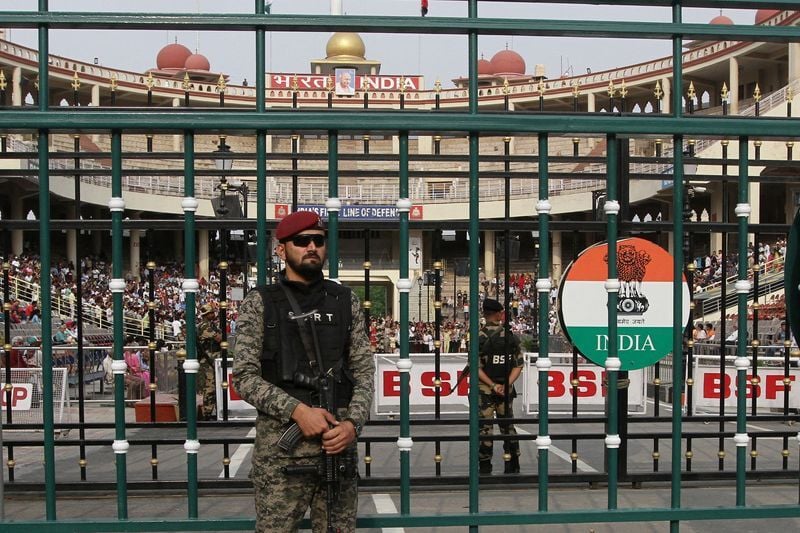

For analysts, this marked a turning point in a partnership that has spanned nearly eight decades, deepening in ways that could reshape alignments in both South Asia and the Gulf. Yet, the pact arrives at a time of heightened volatility. Only months earlier, India and Pakistan exchanged strikes on each other's military sites, a four-day confrontation that brought the subcontinent to the edge of war. Against this backdrop, the Saudi-Pakistan agreement injects new complexity into an already fragile strategic landscape.

Pakistan's foreign ministry framed the move as a reinforcement of "peace and security," but also as a commitment to deterrence. Such language is familiar in alliance politics, reminiscent of Nato's Article 5 but embedded within the rivalries of South Asia and the Middle East. Scholars like Kenneth Waltz have long argued that states seek security guarantees not only to balance threats but also to hedge against abandonment (Theory of International Politics). For Islamabad, the pact symbolises precisely that: a counterweight to fears of isolation.

Saudi Arabia was one of the earliest states to recognise Pakistan in 1947, and since then, the relationship has often transcended diplomacy. Pakistani officers have trained thousands of Saudi personnel since the 1960s, while Riyadh's financial lifelines have repeatedly stabilised Pakistan's struggling economy. In 1982, a bilateral framework ensured the continued presence of Pakistani military contingents on Saudi soil.

Yet, the timing of this latest agreement is critical. The Middle East's security order is under stress. Israel's prolonged war on Gaza, cross-border strikes in the Gulf, and the June confrontation between Israel and Iran—all underscore what Barry Buzan and Ole Wæver describe as the "regional security complex" where insecurities are interlinked and crises spread quickly (Regions and Powers). Against such uncertainty, Gulf monarchies are reassessing their heavy dependency on US protection.

Washington still maintains 40,000-50,000 troops across the region, but US credibility is eroding. The Doha attack on September 9—when Israeli missiles struck a neighbourhood sheltering Hamas ceasefire negotiators—raised new doubts about whether Gulf capitals can rely solely on the US security umbrella. As one Gulf diplomat quipped privately, "If the fire comes to our doorstep, we need neighbours, not distant protectors." Within this climate, Pakistan's presence as a "Muslim-majority nuclear power" carries symbolic reassurance.

Still, Washington views the latest Saudi-Pakistan agreement with unease. The Biden administration already sanctioned Pakistani firms over missile development, openly questioning the range and intent of its arsenal. As Stephen Walt argues in The Origins of Alliances, great powers fear smaller allies drawing them into conflicts they would rather avoid. A pact that could, in theory, interconnect Pakistan's disputes with India and Saudi Arabia's rivalries with Iran raises precisely such concerns.

For Islamabad, however, clarifying boundaries is crucial. Analysts stress that while Pakistan's nuclear doctrine is India-centric, Riyadh may still hope for an implicit shield. Past conversations—cited by journalist Bob Woodward—suggest Saudi leaders floated the possibility of "buying" deterrence from Pakistan if needed. Yet, no evidence indicates the new agreement extends to nuclear assurances. As Dr Asfandyar Mir of the Stimson Center noted, such treaties often carry ambiguity, but ambiguity itself can be a strategic tool, signalling commitment without binding operational pledges.

The pact does not exist in a vacuum. It risks tying Pakistan more closely to Saudi Arabia's fraught regional rivalries, particularly with Iran. For decades, Islamabad has tried to balance ties with Tehran even as sectarian tensions and border incidents strained trust. By aligning formally with Riyadh, it could find itself constrained in mediating between its two important neighbours.

At the same time, Saudi Arabia now places itself within South Asia's tense nuclear dyad. If conflict between India and Pakistan reignites, Riyadh may face indirect exposure. As Hedley Bull argued in The Anarchical Society, order in international relations often depends on great powers restraining local conflicts. In this case, however, an external partner could deepen, not dampen, escalation risks.

Unsurprisingly, New Delhi is studying the pact carefully. Relations between India and Pakistan hit new lows after the April attack in Pahalgam, which killed 26 civilians. The skirmishes that followed in May—the most intense since Kargil—ended only after external mediation. India's foreign ministry has now stated it will "assess implications for national and regional stability."

India's growing ties with Riyadh complicate matters further. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi's third visit to Saudi Arabia this April underlined energy and investment partnerships. While Saudi Arabia has been cultivating closer relations with India, the SMDA with Pakistan suggests that Riyadh is hedging, unwilling to rely on a single partner.

From a structural perspective, this agreement illustrates the changing nature of alliances in a multipolar order. Unlike Cold War-era treaties, today's pacts rarely bind states into rigid blocs. Instead, they act as political signals—gestures of solidarity that may or may not translate into military intervention. Yet, even as political statements, such agreements carry weight. They recalibrate perceptions of strength, deterrence, and vulnerability.

For Pakistan, securing Saudi backing helps offset economic weakness and strategic isolation. For Saudi Arabia, engaging a nuclear-armed ally bolsters credibility at a time when US guarantees appear shakier. But both must manage the risks: entanglement, misperception, and overextension. As Mir warned, every new pact opens questions about scope, resources, and limits.

Saudi oil wealth fused with Pakistan's nuclear shadow may alter the balance of power in both the Gulf and South Asia. It could constrain Iran's influence, complicate India's manoeuvres, and signal to Washington that Riyadh has alternatives. Yet, it is also a gamble. The more the agreement is perceived as binding, the higher the risks of unwanted entanglement.

As with many alliances in history, its true significance will emerge in the crises yet to come. For now, the Saudi-Pakistan pact stands as both an affirmation of old bonds and a reminder that in a volatile region, every alliance is a double-edged sword.

Syed Raiyan Amir is senior research associate at The KRF Center for Bangladesh and Global Affairs (CBGA). He can be reached at raiyancbga@gmail.com.

Views expressed in this article are the authors' own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments