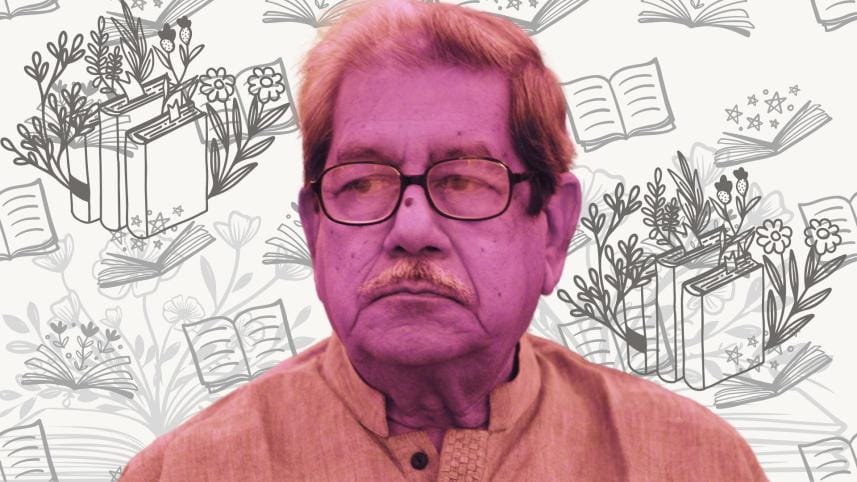

Professor Anisuzzaman: Scholar, Mentor, Friend

He was known just as Professor Anisuzzaman. Most people of his generation used to have longer names. And indeed he did have a longer name as I learned when I started to check online: Abu Tayyab Muhammad Anisuzzaman. But he was always known by just one name.

Born in Bashirhat on February 18, 1937, he moved with his family to Kolkata, then, after Partition, to Khulna, and finally to Dhaka which became his home. An academic, a scholar, and a writer, he was also an activist, taking part in the Language Movement in 1952 and working for the Bangladesh government in exile in Kolkata during the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971. When the Constitution of Bangladesh was written, it was written in English and then translated into Bangla. Dr Anisuzzaman was responsible for the Bangla translation. In 2008, Dhaka University awarded him the title of Professor Emeritus. Ten years later, in 2018, the government honoured him as National Professor. He served as Chairman of the Trustee Board of the Nazrul Institute and was president of the Bangla Academy from 2011 till his death from Covid in 2020.

Professor Anisuzzaman completed his master's in 1957 in Bangla from the University of Dhaka. Five years later, in 1962, he completed his PhD at the age of 25 from his alma mater. A true scholar, during 1964-1965, he was a post-doctoral fellow at the University of Chicago and, during 1974-1975, a Commonwealth Academic Staff fellow at the University of London. He was a visiting fellow at the University of Paris (1994), North Carolina State University (1995) and the University of Calcutta (2010), and a visiting professor at Visva-Bharati (2008-2009, 2011).

His PhD thesis was published in 1964 as Muslim Manas O Bangla Sahitya (The Bengali Mind and Bangla Literature). Among Professor Anisuzzaman's numerous publications, his study of factory correspondence in the India Office Library is significant. Published as Factory correspondence and other Bengali documents in the India Office Library and Records (1981) the volume catalogues a collection of Bangla correspondence dated between 1774 to about 1814, between the East India Company Representative in Dhaka with agents who ordered and supplied cotton textiles for export to Europe. These documents had not previously attracted the attention of cataloguers or readers. As K. N. Chaudhuri, in his brief review of the volume in Bulletin of SOAS, volume 46, issue 1 (1983), notes, "The catalogue would be of great assistance to any historian interested in the economic history of Bengal at the end of the eighteenth century." Professor Anisuzzaman's book Creativity, Reality and Identity (1993), which contains four papers presented on different occasions, includes part of the introduction to this volume.

Professor Anisuzzaman received the top national awards: the Bangla Academy Literary Award for research (1970), the Ekushey Padak for education (1985), and the Swadhinata Padak for literature (2015). Rabindra Bharati University, Calcutta, honoured him with an Honorary D.Lit, (2005); Asiatic Society of Kolkata awarded him the Pandit Iswarchandra Vidyasagar Gold Plaque (2011). The Government of India honoured him with the Padma Bhushan for his contribution to literature and education (2014).

In 1961, when I enrolled in the Department of English at Dhaka University, Professor Anisuzzaman was working on his doctoral dissertation. As a student of the English Department, I had no reason or occasion to meet Dr Anisuzzaman. By 1969, however, Dr Anisuzzaman had started teaching at the newly founded Chittagong University. The university was looking for English teachers—even a teacher with a simple BA Pass, but with a First Class MA degree, was welcome. Chittagong University was several miles away from Chittagong town, and one got to know not only the teachers of one's own department but of others as well. It was then that I first met Dr Anisuzzaman. It was not an exceptional meeting, but my husband was very excited when I told him. My husband's family had migrated from Calcutta shortly after Partition. It so happened that Dr Anisuzzaman's family had lived in the same area. His father, a homeopathic doctor, was well-known to my husband's family.

In December 1970, I had to resign from the university for personal reasons. In 1972, I joined Dhaka University. I lost touch with Dr Anisuzzaman, who remained at Chittagong University. However, he must have visited Dhaka frequently at the time because his supervision of the Bangla version of the constitution would be ready in November that year. At the time I did not know Dr Anisuzzaman's role. I only knew that Dr Kamal Hossain was actively involved in preparing it—and that Shilpacharya Zainul Abedin had been in charge of its aesthetic aspect. (Little did we know at the time, that the constitution, prepared with such pride, would undergo several amendments and, by 2024, prove controversial.)

In 1985, Dr Anisuzzaman rejoined the Department of Bangla at Dhaka University. I was not in the country at the time, and it was only after I returned that I would see him in the teachers' lounge. Then he retired—as I did a couple of years later. I was appointed Supernumerary Professor in my department, teaching one class every Tuesday. After class, I would have lunch at Dhaka Club. Very often I would see him also at the Club, and we would exchange pleasantries. If he or I had already started eating, I did not feel obliged to accept his offer to move to his table. A couple of times, however, we both entered at the same time and then I could not refuse his offer to lunch with him.

In October 2011, I received an invitation from Sustainable Development Policy Institute, Islamabad, Pakistan, to present a paper on Rabindranath Tagore at their conference on "Redefining Paradigms of Sustainable Development in South Asia" to be held in Islamabad in December that year. I informed the organisers that I was not a Tagore scholar. There were several excellent Tagore scholars in Bangladesh, and I could pass on their names to them. The organisers insisted that the invitation was for me. I had been specifically invited by Mr Ahmed Salim, one of the organisers, a poet and short story writer, who had been jailed in 1971 for his support for Bangladesh.

I didn't see how a paper on Tagore would fit into the conference theme, but I was assured that there would be other papers on writers and my paper would be quite in place. In other words, a paper on Tagore was expected from me. What could I write on Tagore that would be of interest to a Pakistani audience? In the sixties, the central government had banned Tagore songs on East Pakistan radio and television, but the people of Bangladesh had resisted. During 1971, Tagore's "Amar Sonar Bangla" had been the tune that reverberated through every Bangalee mind. And, in 1972, the song became our national anthem. Tagore is the only poet whose songs have become the national anthems of two nations. How does "Amar Sonar Bangla" represent Bangladesh? And how does Tagore's "Jana Gana Mana" represent India? I decided to write on "Rabindranath Tagore and the Creation of National Identity." However, where did I begin?

I knew Dr Anisuzzaman was a scholar. Hopefully, he could guide me. I called him, and he was most welcoming. When I reached his house, he was ready with photocopied material that he thought would be helpful. Yes, I was able to get a lot of information online, but that discussion with Dr Anisuzzaman gave me the courage to write a paper on a subject I had never studied before. Mrs Anisuzzaman had been the librarian at IBA where my daughter-in-law studied, so I briefly knew about her. What I was not prepared for was the hospitality she showed someone taking up her husband's time. A tea trolley rolled in with sweet and savoury snacks. Siddiqua Zaman, to give her her own name, must have shown that hospitality to the many visitors who came to meet her husband, and she must have greeted them with the same smile. Afterwards, I learned that she had met Dr Anisuzzaman in 1959 and married him two years later, in 1961. Apart from hosting guests who came to visit her husband, Siddiqua Zaman had to suffer his long absences when he went off on his foreign teaching assignments. It was only the nine months when he was in London, from 1974-1975, that the family accompanied him. The best years of her life, she told me later, were the three months they spent at Santiniketan.

That was the first of several visits to their place. The last few I remember because of the police guard at their entrance. In 2015, bloggers Avijit Roy, Washiqur Rahman, Ananta Bijoy Das, and Niloy Neel were hacked to death with machetes. In October that year publisher Faisal Arefin Dipon was similarly killed in his office. Dr Anisuzzaman had condemned these killings. He received a death threat that he too would be killed in exactly the same way. The threat was serious, and he was provided police protection.

I met Dr Anisuzzaman at the launch of Syed Waliullah's posthumously published The Ugly Asian at the Dhaka Lit Fest in 2018. He looked quite well in his white kurta and white dheela pyjama. He did not look quite so well when I last met him on January 25, 2019, at a conference at East West University. A little over a year later, on May 14, 2020, he passed away from Covid. A personal loss for his family, his death was also a loss to the nation of a lighthouse, and, to me, of a mentor and friend.

Niaz Zaman is a retired academic, writer, translator, and publisher. She was nominated for the Ekushey Padak this year for her contribution to education.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries, and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments