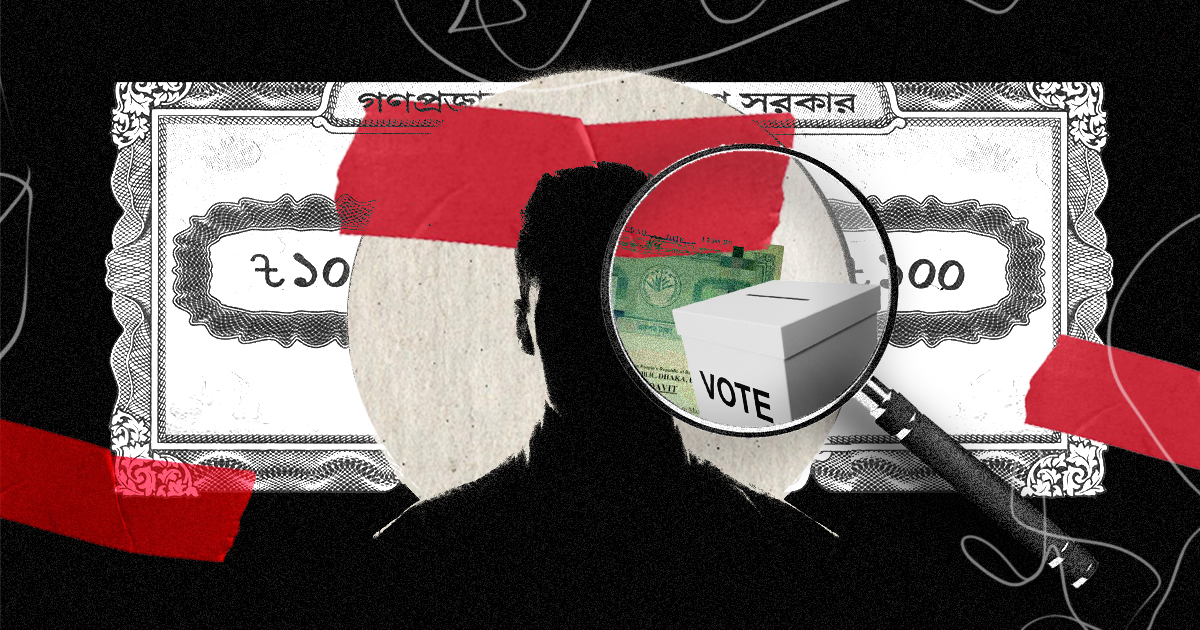

A Potemkin election in Bangladesh?

The phrase "Potemkin village" refers to an elaborate facade designed to hide an undesirable reality. According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, the term comes from a popular myth where Grigory Potemkin, then governor of New Russia (modern Cremia), constructed fake villages to impress foreign dignitaries accompanied by Russian empress Catherine the Great in 1787. The legend goes that Potemkin would construct a pasteboard village—complete with waving, happy peasants—in advance of Catherine's arrival and deconstruct it shortly after she left, repeating the same charade over and over.

While the authenticity of this story is disputed, the term stuck and is now used by many observers to describe fake elections under authoritarian regimes. For example, in How to Rig an Election, Nic Cheeseman and Brian Klaas describe Potemkin elections as elections where "the pageantry of campaigning, the parade of voting, the charade of counting, all are engineered with one simple goal – to fool the West into believing that all was conducted fairly in a shining model of democracy. But behind the facade, the actual democratic scaffolding is often rotten – if it exists at all."

Alina Polyakova, in her article titled "Putin's Potemkin Election," vividly portrayed what they actually look like. Terming the Russian general election held on March 18, 2018 a "theatrical production," she said it involved elaborate stage settings, set designs and a handpicked cast of actors. A well-funded promotional campaign—with posters plastered across the country, highly produced television ads, and constant announcements on public transit—ensured a packed house on the day of the premiere. The star of the day was Vladimir Putin, and the production was the Russian presidential election. While it had all the trappings of a normal democratic election, it offered citizens no real choice. The most interesting part of the so-called election was not the result, but the impressive mobilisation capacity displayed by the state to physically get people to the polls to cast a meaningless vote in an "election" where the outcome was already known.

One may say that the upcoming election in Bangladesh resembles the aforementioned Potemkin election format. The government, the Election Commission and its commissioners, law enforcement agencies, candidates, and voters all know what is actually going to happen on January 7, 2024. But even then, the government is trying to make the election process seem credible.

Elections in democracies are usually hotly contested. The fiercer the competition, the more uncertain the outcome. But authoritarian rulers are not comfortable dealing with these challenges, and want to remove all uncertainty—usually by force. One way to eliminate electoral uncertainty is to abolish the electoral system altogether. But this poses the risks of local and international condemnation, alongside economic sanctions. So, modern authoritarian rulers need a system in which there will be elections, but without electoral uncertainty. It is from this urge that an election is turned into a staged drama.

Organising electoral drama is not easy. In addition to the ruling party, "proper" opposition parties, election commissions, election officials, law enforcement agencies, bureaucracy, judiciary, domestic and foreign election observers, etc are needed to complete the cast for the drama. Of these, the trickiest to manage are "appropriate" opposition parties. Naturally, real opposition parties will be reluctant to participate in such an orchestration. So, political, administrative, and/or legal pressures are created to force them to participate in the Potemkin polls, or favourable alternative opposition parties are created.

All active anti-government political parties in Bangladesh—including BNP, the major opposition party on the streets—are demanding the election to be held under a non-partisan, neutral government. They have refused to participate in the election under the ruling government, citing the experience of past questionable elections in 2014 and 2018. With BNP remaining rigid in its stance, thousands of the party's leaders and activists, including its central leaders, have been arrested and jailed, while hundreds of activists have been sentenced in "ghost cases." Attempts have also been made to lure BNP leaders into Trinamool BNP and Bangladesh Nationalist Movement (BNM), the two parties known as the "King's parties", to participate in the upcoming election, But with few exceptions, there has been little success on this front.

But an election without any competition will not be acceptable at home or abroad. To combat this, the ruling Awami League has encouraged its leaders to compete as independents or "dummy candidates" against its own nominated candidates. Although 27 out of 44 registered parties are participating in the election, none are strong enough to compete against AL. To keep the allies in its fold, AL decided to share six seats with the 14-party alliance and withdrew 25 of its own nominees from the race to allow Jatiya Party (JP) an easy win in those seats.

As a result, there will be an election on January 7 in which the nominated candidates of the ruling AL will "compete" against its dummy candidates, while the main "opposition" party will be elected with the ruling party's support. So, this election will likely be nothing but a friendly match between AL and its allies—the winner of which is already decided. Like Russia's Potemkin election, the main challenge will be to ensure enough voter turnout so that it looks participatory enough. For this, AL has reportedly formed 42,000 committees for each polling centre whose task will be to bring recipients of government benefits to the polls on election day, besides AL's own voters. To this end, the ruling party will conduct door-to-door campaigns and arrange transportation for the voters.

Competition among participating political parties is vital during elections. But if the competition is confined between the ruling party and its allies, then there is no risk of the former losing power. Hence, the election is robbed of its accountability mechanism.

In Bangladesh, even though elections are held every five years, the people are deprived of the accountability process that a genuine election would feature. Due to this unaccountable, monopolistic rule, the human rights situation, the state of the rule of law, and the economic crisis have seriously worsened in the country. Since the competition on January 7 will only be limited to the ruling party's own circle, there is hardly any possibility of this election positively impacting our political and economic conditions.

Kallol Mustafa is an engineer and writer who focuses on power, energy, environment and development economics.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments