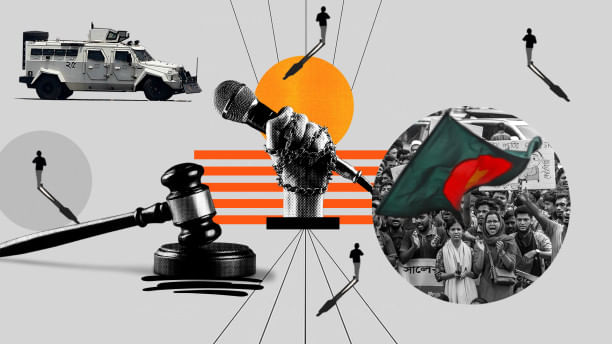

Our transitional political settlement and ways forward

The sham election of January 2024 was a turning point for Bangladesh. In my research and teaching roles, I began to observe young people openly saying that only violence can remove the shoirachari party. If that feeling becomes widespread, all it needs is a spark. When the one-point demand emerged out of the repression of students, the mass uprising that followed was not really a surprise. The students announced the government would fall in July. They also announced, as only students can, that July would be extended if necessary. July only needed to be extended to the 36th before the regime collapsed in a bloodbath. What can we do to consolidate this hugely costly achievement?

In my view, a useful way of thinking about a social order is as a political settlement—a description of the power, capabilities and interests of the organisations in a society. Organisations and their interactions deliver the social, political and economic outcomes of a society. This social structure is ultimately held together by a distribution of power. A political consensus can support this distribution of power, or challenge it, but it cannot sustain a social order on its own. In developing countries in particular, power is partially reproduced through many rules that are informal, involving corruption, clientelism and patronage. If these informal "rules" or institutions cannot be blocked by other organisations, they are part of the political settlement. Societies, therefore, differ greatly in terms of how power is reproduced, who benefits, and the path of development. But in every case, the rules that are followed or violated depend on the power and interests of competing organisations.

Over the last 10 years, power was reproduced in Bangladesh by a ruling coalition using a combination of repression, fear, and mega-corruption that allowed the enrichment of party supporters and consolidated their power. Over time, economic and political power became more and more concentrated as illicit wealth concentrated at the top. The middle was increasingly hollowed out, and competing political organisations were almost entirely destroyed. This corroded the viability of the economy, and political opposition became almost suicidal, but the political settlement remained stable, till the 36th of July. The student-led mass uprising succeeded precisely because it was not an organised force. The students did not have an organisation that could be destroyed, and despite increasingly violent attempts to reproduce fear, this time violence increased the determination of the street. The political settlement that eventually emerges will depend critically on how the force on the streets translates into new organisations.

The student-led mass uprising succeeded precisely because it was not an organised force. The students did not have an organisation that could be destroyed, and despite increasingly violent attempts to reproduce fear, this time violence increased the determination of the street. The political settlement that eventually emerges will depend critically on how the force on the streets translates into new organisations.

New laws or even constitutions will not change the political settlement if the rules are not followed. Why do we often see people standing in an orderly queue in one part of Dhaka and the same people breaking a queue not far away from the first one? If you think about it, this cannot be explained by culture, because it is the same people, or by external policing, because it is the same country. The critical factor is usually the distribution of power within the queue, and how people in the queue assess how others will react if they break the line. If everyone in the queue has similar power, the first point of enforcement comes from other people in the queue. In countries with a strong rule of law, the first point of enforcement for violators comes from their peers, because the distribution of power and capabilities creates this self-interest across organisations. Without these "horizontal checks," formal enforcement by police, courts or regulators is never very effective and the enforcers are rapidly corrupted.

The deeper problem in developing countries is that most of our organisations are not likely to fully behave like this immediately. They vary greatly in power and capabilities. Moreover, for most businesses, it is not essential to have a reputation for following rules. They can do most of their business using informal assurances to their suppliers and clients. These are characteristics of developing countries. They rarely have either the interest or the power to check formal violations by others, and are happy if they can do some violations of their own, like not paying taxes or bypassing regulations. In this context, political parties raise money from black sources, and subsequently exercise power by distributing money-making opportunities from the top, rather than collecting legal donations and delivering on a manifesto. Nevertheless, even in this adverse configuration of power and capabilities, how organisations are networked and collectively organised may result in very different political settlements and social outcomes.

During our democratic interlude in the 1990s, most economic and political organisations in the country were grouped around two coalitions. They were both corrupt, engaged in many violations, but there were some effective checks and balances. This was not an advanced country liberal democracy. I described it as a "competitive clientelism." But the checks meant that no coalition had the time to hollow out entire banks or fully destroy the police or courts. But from 2014, this political settlement radically changed. The Awami League destroyed all effective means of replacing it through elections. It began destroying opposition organisations, parties, banks, businesses and eventually even sympathisers. By allying with the ruling party, big businesses rapidly became bigger and business organisations became more concentrated. The SMEs that had driven Bangladesh's growth in the previous decade languished. No new sectors emerged. Overpriced power and infrastructure projects gave the impression that the GDP was rapidly growing. In a paper I wrote in 2017, titled "Anti-Corruption in Bangladesh: A Political Settlements Analysis," I argued that the new settlement was a "vulnerable authoritarianism," with many features similar to Pakistan in the 1960s. It was based on destroying the opposition and instilling fear in others. Ironically, it also shared the same false narrative of development first and democracy later. It was not a dominant party settlement, where a single party includes most political organisations within it. A true dominant party is less violent, more stable, and it does not collapse in a bloodbath. My analysis was correct.

Now that the authoritarian political settlement has collapsed, the vested interests within business and the administration are being temporarily held at bay by vigilance on the streets, and Prof Yunus's interim administration. The entire society is holding its breath, but we must help much more actively. This current temporary settlement is fragile. The damage done by the Awami League makes even a return to competitive clientelism difficult. Opposition parties and middle sections of business have been hollowed out. The Awami League itself is a pariah with its leadership on the run. If the economy falters, a counter-revolution based on a coup cannot be ruled out. We have to work quickly to construct viable networks and organisations that can collectively exercise power to support more progressive rules than the ones that existed. Attempting too much or too little can be dangerous.

The new political settlement will emerge out of the transitional one. The transitional distribution of power is one where the unorganised force of students and citizens is valiantly checking established vested interests. This cannot last unless some of the unorganised power is converted into organised networks: new coalitions of businesses, students, political actors. They should not promise what they cannot deliver, but they should promise what their effective power can deliver in terms of enforcing better rules and strategies. This debate must intensify and inform our leadership.

Dr Mushtaq Khan is a professor of economics at SOAS University of London.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guideline for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments