Our fiscal space is narrowing fast

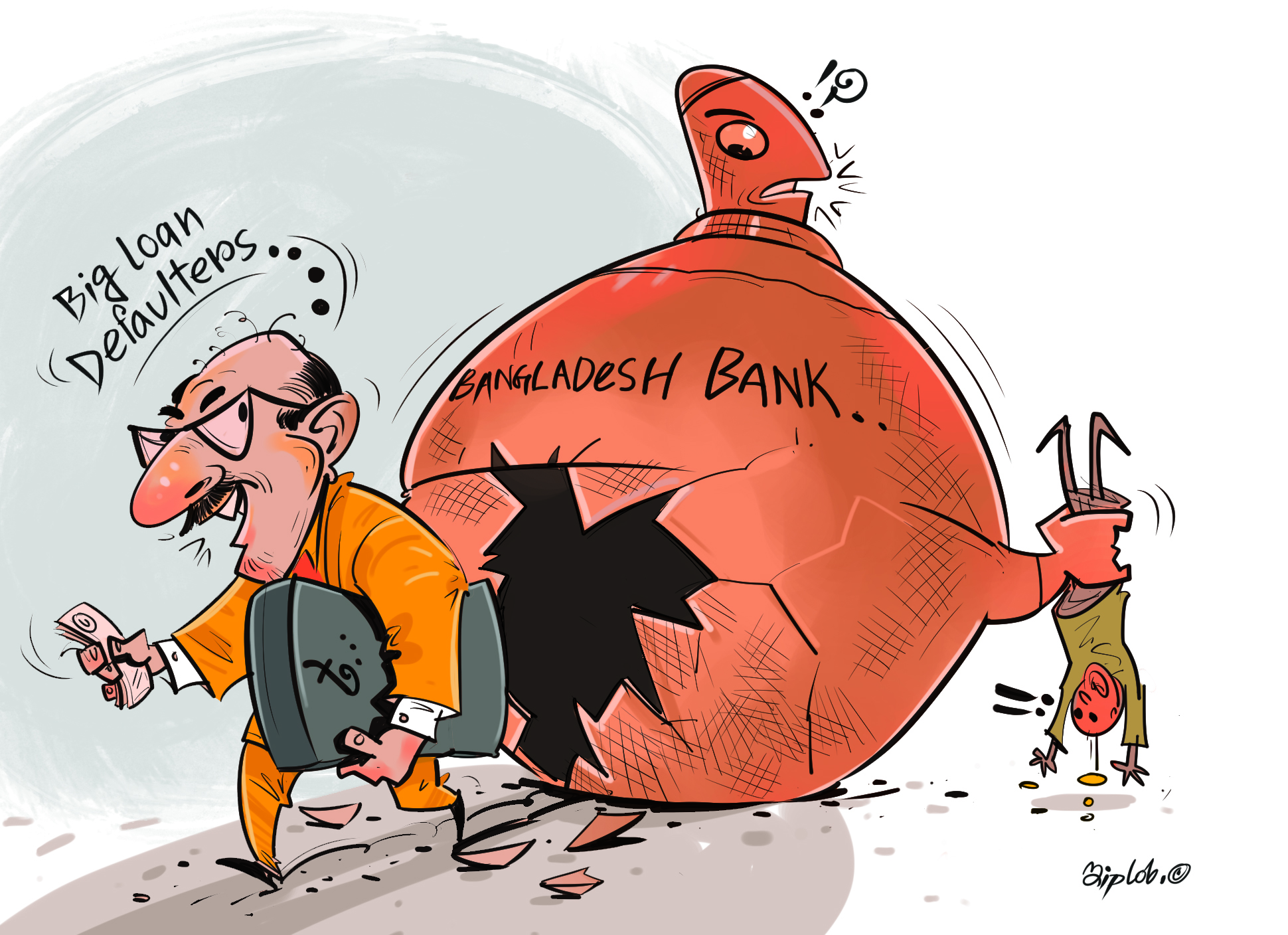

At the moment, Bangladesh is facing a number of challenges in maintaining macroeconomic stability, with the taka depreciating against the US dollar due to increased import bills, coupled with declining export earnings and remittance inflows. This is made worse by the global economy at large going through a recessionary (or stagflationary) period, with a fall in economic growth and a surge in prices in many large economies.

Both global and local macro-challenges can have a number of serious implications for the general citizens of Bangladesh.

First, the economic contraction of our trading partners can have negative implications for export earnings, which can affect the process of industrialisation and employment generation. The energy crisis is only adding to this and negatively impacting industrial production. Austerity measures taken by the government to contain inflation (and to curtail import payments) could also affect employability prospects. In the short- to medium-term, all of these factors could reduce household income and expenditure.

Secondly, the falling value of the taka is not only putting pressure on our foreign exchange reserves, but also adding to our import bills. With our import basket containing many essential food items, the appreciated dollar value is triggering further inflation. And it goes without saying how the government raising the price of fuel by a significant margin (to balance losses they had incurred previously due to high subsidies) has affected the livelihoods of the average Bangladeshi.

While there could be a fall in global energy prices due to the global recession, the ongoing war in Europe has added a lot of uncertainty into the mix. Besides, if our export and remittance earnings continue to fall, it will put further pressure on the value of the taka, making fuel even costlier to purchase.

In general, there are at least two ways in which increased energy prices are affecting our daily lives: through an increase in the direct cost of transportation and communication, and through an increase in the price of essentials due to higher transportation costs.

Continuing subsidies and reducing indirect taxes to contain the prices of fuel and essentials could shrink our already narrow fiscal space, leading the government to curtail expenses in health, education and social safety net programmes. Any reduction in the safety net expenditure in particular can hit lower income groups hard, especially against the backdrop of rising prices of essentials.

Without a proper support system, higher inflation can, on one hand, push already vulnerable members of the population below the poverty line, and on the other hand affect the quantity and quality of people's food intake. In the latter case, lower food consumption can have crucial implications for the nutrition and health of children and adolescents. Besides this, the increasing prices of necessities could compel households with fixed incomes to curtail expenses on their children's education and/or postpone crucial health expenditures. Increased spending on essentials can even compel some families to discontinue children's education. In this case, while any child could end up joining the labour force, girl children might be forced into marriages. The social costs of inflation can therefore be far-reaching.

The government now must decide on whether they will move towards a market-based exchange rate system to restore macroeconomic stability. If we do not manage to stabilise the exchange rate, we could be faced with a more depreciated value of the taka, and that can trigger inflation further.

The government might also need to adjust import duties and value added taxes – at least in the short term. It is now essential to cut down on unnecessary expenses, especially operating expenses, and to carefully consider and select which development projects to work on while strictly monitoring their performance.

On the other hand, a thorough reform of the direct taxation structure to broaden the fiscal space is crucial. Any reforms in subsidy policy must be done in phases, with careful planning. For instance, subsidies for agriculture should receive the highest priority.

In order to contain inflation, the relevant authorities are already taking austerity measures, which can constrain employment generation and affect households' income. It is therefore crucial to provide support mechanisms to workers through adjustment of wages, subsidised food items, and more. It is also crucial to expand the government's safety net programmes to safeguard economically vulnerable members of the country's population. In addition to expanding coverage, raising per capita allowances is a need of the moment.

In order to eliminate the "unexplained" aspect of inflation – which is often caused by manipulation of, and inefficiency and disruption in, the supply chain – greater emphasis needs to be put on effective market monitoring.

Dr Sayema Haque Bidisha is a professor at the Department of Economics of Dhaka University, and research director at the South Asian Network of Economic Modeling (Sanem).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments