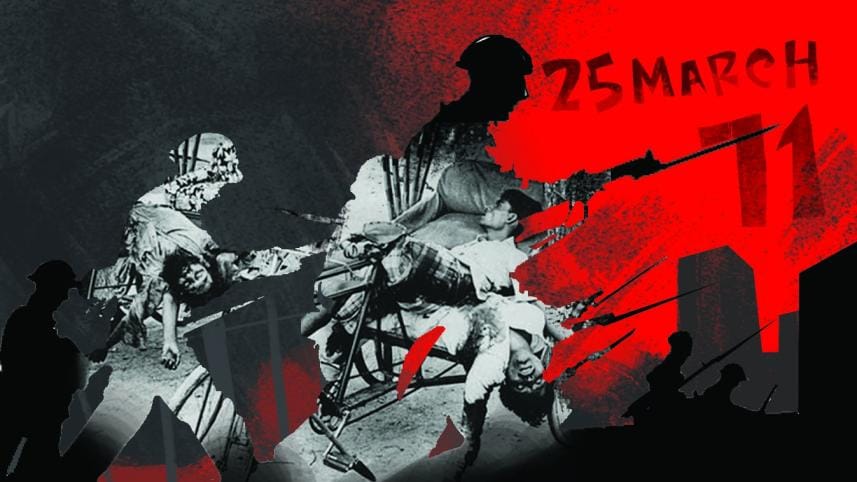

March 25 through the eyes of ordinary people

March 25, 1971 marks the darkest yet most significant moment in the independence struggle of Bangladesh. It began with the Pakistan government launching Operation Searchlight, abducting and killing thousands of people in a single night in the first episode of what went on to be a ruthless genocide. It also sparked an armed resistance that led to the birth of this country. Here are three personal accounts about the victims of this dark night.

'I'll be back, pray for me'

Nazma Majid

In 1971, my husband was the chief of police in Rajshahi. On March 31, the Pakistan Army's Captain Salman Mahmud took him away from our drawing room. Since then, he has been missing. One can easily guess what fate befell him. Leaving behind his wife and four children in despair, he became a martyr.

Born in 1935 in Rangpur, Shah Abdul Majid was the son of Shah Yunus Ali and Mosammat Meher Afzun. He was brilliant from an early age. He always ranked first and received scholarships, so my father-in-law never had to worry about his educational expenses throughout his secondary and higher secondary education. After completing his master's degree in Political Science from the University of Dhaka in 1956, he taught at the then Jagannath College from 1957 to 1961. During this period, he passed the Central Superior Services (CSS) examination and became a member of the then Pakistan Police Service. The results of his CSS exam were published on the day our first son was born in 1961.

I had seen how calm, soft-spoken, and principled my husband was. He repeatedly asked me whether he should take the job, as he was unsure whether he could be as strict as the police service often required. While teaching for three years, he earned a reputation as a beloved educator among his students. Nevertheless, he eventually accepted the position in the police department.

After completing his training at the Sarda Police Academy in 1962, he joined as an assistant superintendent of police (ASP) in Chittagong in 1963. In 1964, he joined the Special Branch of police, and from 1965 to 1968, he served as the additional superintendent of police in Dhaka district.

At that time, Abdul Majid's voice often calmed and disciplined the agitated students protesting in Dhaka. Though he held a position of authority in the police, he still carried the firmness and affectionate discipline of a teacher. Later, he served as the superintendent of police (SP) in the districts of Bogura and Faridpur, as well as the vice-principal of the Sarda Police Academy. In September 1970, he assumed the role of SP of Rajshahi district.

During the tenure of Monem Khan, when he was posted in Dhaka, the student movement erupted. There were countless days and nights when he would go without meals, he would remain awake and restless, concerned about his duty and the safety of the students.

He would tell me, "Since fate made you a police officer's wife, you must stay strong. Remember, my life is like water on a lotus leaf, it can slip away at any moment." He believed that if he stood before the students, they would calm down. Then, he took charge as the SP of Rajshahi. From the very beginning, an inexplicable sense of fear lingered in me. It felt as though I was destined to lose something there.

Then came March. The non-cooperation movement left him deeply worried. He would say, "Who knows what's coming." He was anxious.

The dreadful night of the 25th arrived. That night, members of the military swarmed our area. My husband knew that he could be arrested at any moment. I told him to leave, but he responded that it was unbecoming of a police officer's wife to say such things. He angrily asked, "If I leave, who will lead my police force?"

He tried to convince the staff at police lines to disperse and resist the enemy. The Pakistani soldiers had blockaded the area. But my husband was determined to prevent the police force from perishing unprepared and surrounded by the enemy.

When the bloodthirsty Pakistani officer Captain Salman Mahmud arrested my husband on March 31, 1971, I was told he was being taken for questioning and would return shortly.

Before leaving, he said to me, "I'll be back—pray for me." Yet, the patriotic Shah Abdul Majid never returned to the warm, loving life he shared with his wife, sons, and daughters.

Nazma Majid is the wife of the martyred Shah Abdul Majid who was an educationist and the superintendent of Rajshahi police.

For my husband, the nation came first

Sabera Haq

"Who should I call Abba? Everyone calls someone Abba! What does Abba mean, Ma?"—my son, Md Nijamul Hoque Sarkar, would often ask me as a child, leaving me at a loss for answers. When my husband was killed by the Pakistani army, Nijamul was just a little over a month old.

Advocate Nazmul Hoque Sarkar, elected as a member of the national assembly from Charghat, Puthia, and Durgapur of Rajshahi in the 1970 elections, was killed by the Pakistani army on the night of March 25, 1971.

On March 25, my husband was entrusted with significant responsibilities for leading the resistance. Following Bangabandhu's directives, he held detailed plans and lists outlining the resistance war, including formation of neighbourhood resistance committees and volunteer forces. Around 10pm on March 25, he moved from the Awami League office to a secret hideout in Hetem Khan. But by 4am, he returned to the Awami League office to move some important and confidential documents. At that time, he was serving as the president of the district Awami League.

After completing his task, he returned to his home in Ranibazar to assess the situation, only to find it in ruins, with broken doors and windows. Acting quickly, he sought refuge at the nearby house of his friend, Khandakar Altaf Hossain. As the situation grew increasingly perilous, the two decided to flee. However, Pakistani soldiers spotted them. Altaf Hossain managed to escape by jumping over a wall into a neighbouring house. My husband, carrying a briefcase containing crucial documents, attempted to run as well. But the soldiers shot him from behind, killing him on the spot. They then took his body away.

His tireless work centred around ensuring the safety of the city's residents and establishing a system of resistance. Meanwhile, I, along with my sons, sought refuge at my uncle Badiuzzaman Tunu's (Bir Pratik) house in Miyapara, near the public library.

Late on the night of March 25, the Pakistani soldiers raided my house. At that time, only Israil, a peon from Krishi Bank, was there. Failing to find my husband, the soldiers brutally beat him and even attempted to kill him. They set fire to the furniture in the house, while the Biharis looted all our belongings. Not finding my husband, the frustrated Pakistani soldiers turned violent and stormed into the home of veteran politician Advocate Ramesh Maitra, which was located nearby. There, they mercilessly beat him and used every possible means to try to extract information about my husband's whereabouts.

I received the devastating news on March 29 that the Pakistani army had taken away my husband. With the guidance and support of well-wishers, I fled the country, carrying my one-year-old child in my arms, and facing an uncertain and hopeless future. I crossed into India in mid-April. Such is the fate I was destined to endure—our marriage lasted only six and a half years. What is the point of grieving now? The pain is most unbearable when I look at my children's faces. They never knew their father. They were deprived of his love and care.

Now, all my love, devotion, and purpose revolve around Shaheed Nazmul Hoque Girls' High School. The success of the school and its students brings me joy—it is my way of staying connected to my husband. He was a renowned public servant, a dedicated organiser, and a true patriot. For him, the cause of the oppressed, the party's manifesto, and the nation always took precedence over his own life. Family and household matters were secondary to him. Anyone who visits our home in Ranibazar, where I now live with my three sons, would immediately understand the simplicity and humility with which my husband lived. In our small home, there is no trace of luxury or grandeur—only his memories, a burden I carry alone.

Sabera Haq is wife of martyred Nazmul Hoque Sarkar, a lawyer and Awami League leader of Rajshahi.

'Let me open the door, they won't harm us'

Abdul Hannan Thakur

Fazlu bhai was my paternal cousin. We used to call him Chhotobhai. He was born on March 2, 1939. As a student, he was exceptionally brilliant—always ranking first in every school examination. Despite his restless nature, Fazlu bhai was deeply devoted to his father. Perhaps in his father, he found the warmth and affection of his lost mother. Since her death, he shared a soulful connection with his father—whether it was anger or affection, it was always directed towards him.

He completed MSc from the University of Dhaka (DU) in 1962. On August 1, 1963, he joined the Department of Soil Science at Dhaka University as a lecturer. From childhood, Fazlu bhai had dreamed of becoming a university teacher. That calling became his life's purpose. He immersed himself in research, books and study.

Fazlu bhai earned a scholarship and went to the University of London for higher studies. On July 25, 1968, he received his PhD and rejoined DU the same year. On August 15, 1968, he was promoted to senior lecturer. In 1970, he married Farida Khanam Shirin. Farida bhabi was also a student at DU. She earned her MSc in Physics with first class and later joined there as a faculty.

It was March, 1971. Teachers and students were united in the spirit of independence. Fazlu bhai also declared his solidarity with the Liberation War. He lived in the university staff quarters near Nilkhet. After his wife left for London, he felt increasingly lonely. When he mentioned this to our eldest sister in Azimpur, she sent her son, Ali Ahsan Khan Kanchan, to stay with him. At that time, Kanchan was a second-year science student at Dhaka College.

Then arrived the dreadful night of March 25. Fazlu bhai went to Azimpur. Our eldest sister earnestly insisted he stayed for dinner. But he declined, saying he would eat later with Kanchan, and hurried back home. The same night, Kanchan visited his aunt Renu's house on Mitali Road, saying the same thing—"I'll have dinner with uncle." A young boy Joban, a relative of Farida bhabi, prepared their dinner at home that night.

Shortly after 10pm, the brutal Pakistani Army took over Dhaka. At exactly 12:20am, they pounded violently on Fazlu bhai's door with their rifles, nearly breaking it down. Inside were Fazlu bhai, Kanchan, and Joban. Following the relentless pounding, Kanchan said, "Uncle, I've had UOTC training. Let me open the door with the gesture of surrender—they won't harm us." Fazlu bhai tried to stop him but failed. The moment the door opened, the soldiers unleashed a barrage of bullets, riddling Kanchan's chest. Overwhelmed by horror, Fazlu bhai shouted in anguish. Instantly, their guns roared again—his chest was also torn apart. They then desecrated his body further by carving an 'X' on his chest with a bayonet. Just like that, two vibrant lives were silenced forever. The horrific scene was witnessed by Joban, who was hiding in the adjacent bathroom. He too had been shot in the leg but somehow managed to survive.

On March 27, when the curfew was temporarily lifted, people went to retrieve the bodies of Fazlu bhai and Kanchan. The scene was beyond description. The house and veranda were soaked in blood—nothing but blood. Congealed, darkened blood. Kanchan's lifeless body lay near the door. One of Fazlu bhai's lifeless hands rested on the steel cabinet beside him as if he were trying to protect something precious. Later, we learned that it contained some belongings of Farida bhabi. Both Chhotobhai and Kanchan were hurriedly buried side by side in coffins at the Azimpur graveyard on March 27. After that, none of us returned home. We fled into the unknown, driven by the fear of the ruthless attackers.

Abdul Hannan Thakur is cousin of the martyred Dr Fazlur Rahman Khan, an assistant professor in the Department of Soil Science at the University of Dhaka.

The accounts are abridged version of memoirs taken from Smrity:1971, edited by Rashid Haider.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments