Making Bangladeshi workers safe for capitalism

On April 6, 2023, the High Court granted bail to Sohel Rana, the owner of the building whose collapse caused one of the deadliest industrial disasters in history. The news came just over two weeks before the 10th anniversary of that day, reminding us again that history repeats itself, "first as tragedy, second as farce." The bail was later halted, but the message was clear, further reinforced by the BGMEA's recent call for an Industrial Police unit in the DMP area and the newly formed wage board announced just days later. None of the labour organisations whose relentless calls for a Tk 25,000 minimum wage finally resulted in a new board were consulted, and the labour representative chosen has a very predictable affiliation.

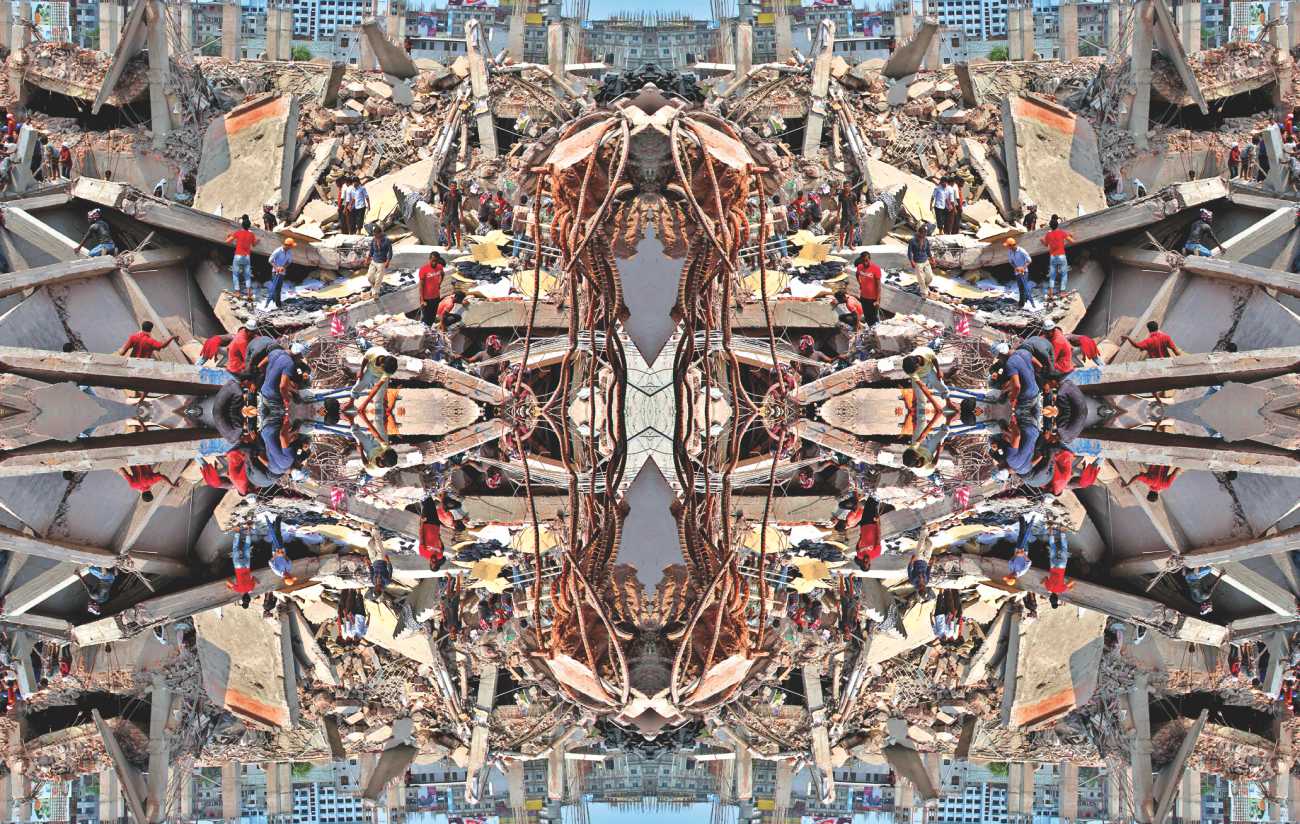

All of this is par for the course, but it does provide a break from the steady dose of self-congratulatory optimism that buyers, factory owners, and the state have been pouring into the industry's "image" in recent years. The narrative is simple: against all odds, our ready-made garment (RMG) industry is not only thriving (aiming for $100 billion exports by 2030), it has also – through the joint efforts of these three parties – made life better and safer for the industry's workers. Exit Rana Plaza, enter happy workers and "green" factories. All of this begs the question: "safer" how, from what, and to what end?

Undoubtedly, it is the brands/buyers that have benefited the most from this celebratory narrative. In the aftermath of the Rana Plaza collapse, these brands, in concert with transnational bodies like the International Labour Organization (ILO), rolled out an elaborate system of fire and building safety codes. Together, the EU-led Accord and US-led Alliance, along with other transnational agreements, made up a multi-level, multi-party "compliance" and monitoring regime (Rahman, The Daily Star, April 21, 2016), which alongside the championing of unionisation has been hailed as ushering a new age of worker safety.

Yet, matters are not that simple, as Dina Siddiqi has repeatedly pointed out. Accord-Alliance became one component in a pre-existing, audit-based global monitoring regime, accountable to no one, functioning primarily to shield Western brands from liability (LeBaron et al., 2017), depoliticising the question of workers' safety and placing the burden on "corrupt" Third World national governments and their "ruthless" industrialists, all while continuing to enable the very same "scandalous" conditions (Siddiqi, Himal Southasian, January 11, 2022). After all, Rana Plaza would not have claimed any lives if the garment workers and only the workers had not been coerced to enter a building that they knew could collapse at any moment. They were killed just as much by production targets as by falling beams.

The most stunning manifestation of this indifference came with the billion-dollar order cancellations we saw during the pandemic. These cancellations also provided our industrialists with an opportunity to use the workers' plight as a bargaining chip, a concern that disappears whenever it comes to unpaid wages, mandatory overtime, denied leave, abuse, harassment, and the disciplining of "troublemakers." We do see it, however, in the celebrations of all that factory owners apparently do for workers, including supporting some of them in higher education. As Taslima Akhter has pointed out, such individual success stories simply distract from the fact that the vast majority of workers are still compelled to sacrifice their education, health, and dignity on a daily basis (The Daily Star Bangla, January 11, 2023). Record-breaking sales also tend to turn into doom-and-gloom narratives whenever workers come knocking on the factory doors for liveable wages. The difference between individualised charity and decent wages, of course, is that the latter can potentially reduce the precarity that ensures the disposability/exploitability of the worker in the first place. Make workers safer, yes, but not too much.

Trapped between foreign capital and our comprador bourgeoisie, it is to the Bangladeshi state that our workers should have been able to turn to. Yet, RMG export dependence has meant a total identification of "national interest" with the industry's profit margin, and it doesn't help that so much of our political class is directly tied to the industry. No wonder, then, that the right of the "small" factory owner to do business trumps the right of workers to have a liveable wage, and that both the law and law enforcement behave as the industry's private service. The tortuous legal processes that have kept the Rana Plaza collapse, Tazreen fire, and other cases permanently suspended (Mustafa, Prothom Alo, April 23, 2023), the total lack of legal compensation for the victims of any of these cases, the legal impediments erected to ensure that only owner- and state-friendly unions get to register and operate (Karmakar, Prothom Alo, May 1, 2021), and the ease with which law enforcement and political muscle is leased out to factory owners eager to discipline workers – all of this leaves little room for doubt.

Three years ago, my colleague Seuty Sabur and I wrote about the total abandonment by the state that workers faced during the time of lockdowns (The Daily Star, April 4, 2020) – an acute manifestation of a more general phenomenon. The fiction of "national wealth" – made possible because of commodity production and the fact that one taka is as good as any other – makes it easy enough to believe that the unprecedented levels of wealth flooding Bangladesh today is everyone's wealth, and we can forget for the moment the gulf between those who command that wealth and those who do not. It is not an accident that the latter are precisely those who are compelled to pour their lives into producing that very prosperity.

What, then, is to be done? Our garment workers face a double bind today, trapped between growing precarity (rural dispossession, skyrocketing prices) and the limits/temptations of an NGO-ised and ineffective trade unionism (Siddiqi, The Daily Star, April 21, 2017). The very structure of supply chain capitalism makes collective action at the site of production toothless, as there is always another factory – and indeed another country – to source from. Under these conditions, factory owners and the state have managed, after years of vehemently opposing unionisation, to transform the registered union into an instrument of labour discipline. Small wonder, then, that garment workers have had the most success through militancy outside of them (Ashraf & Prentice, 2019).

If supply chain capitalism neutralises union action, we may have better luck, as Vijay Prashad (2015) has long argued, with struggles at the sites of living/consumption instead. At the very least, land reform and housing, social welfare, public education and healthcare, utilities, energy and transport, etc are all sites where garment workers' struggles can become interlinked with those of others, and through which workers' lives might become a little less precarious, giving them greater bargaining power on the factory floor.

None of this can happen, however, without directly engaging the state. If fast fashion must dominate the "national interest," then at the very least we must compel the state apparatuses to play a truly mediating role on behalf of "the nation." Are there alternatives to RMG export dependence? Perhaps, or perhaps not, but it does not seem that anyone in the corridors of power is concerned with even considering the question; we must make them. The state remains the only party in the triumvirate over which ordinary citizens, including garment workers, have even theoretical control. Turning that theoretical control into an actual one can make the difference between mere factory "compliance" and workers actually living full and dignified lives.

Shehzad M Arifeen teaches anthropology at the Department of Economics and Social Sciences in Brac University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments