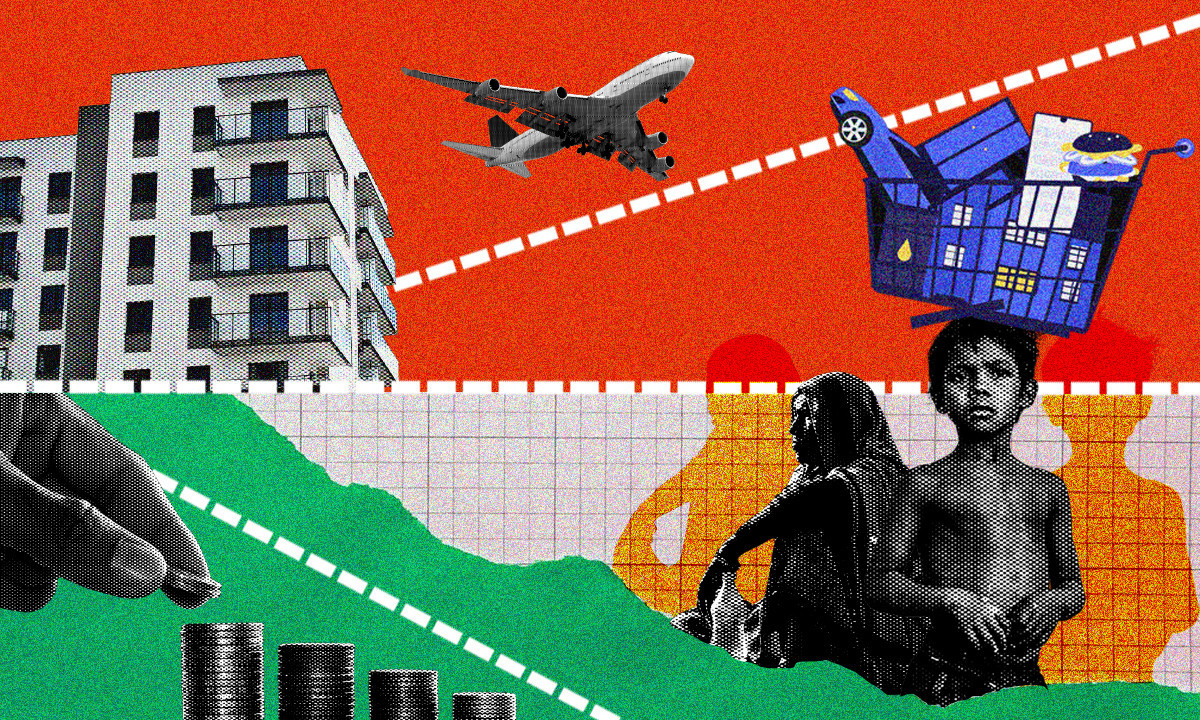

Inflation and inequality fuelling a geography of despair in Bangladesh

There is a tinge of pessimism that seems to run through all of us, a quiet sense of doubt about whether things in the country are truly improving. Financial strain and food inflation have long been familiar concerns, but in recent years, anxiety around social security and political stability have joined them, making daily life feel more uncertain. This sentiment, so often heard about in daily exchanges, is not merely anecdotal. It is reflected in data. The national survey on the State of the Real Economy, conducted by PPRC, shows that pessimism is emerging as a defining feature of households in Bangladesh, weighing heavily on the poor.

Data says that the mood of the economy isn't very optimistic. One in three households (33 percent) in the lowest income decile state that they are pessimistic about their future. When the scope is widened to include the bottom two deciles, nearly a quarter (24 percent) still carry the same bleak outlook. By contrast, data show that 62 percent of the top two deciles express optimism, buffered by resources and networks cushioning them against volatility. This stark divide is not just about material inequality; it also reflects an emotional level. A geography of hope and despair is mapped neatly onto income levels.

What explains such divergence? For poorer families, pessimism is grounded in lived realities. Over a quarter of the bottom decile report being "always in shortage," and nearly four in ten "occasionally in shortage" to describe their current household condition. These are not abstract measures. They mean skipping meals, borrowing to buy necessities, or having a heavy debt burden. By contrast, the top two deciles live in a different reality: nearly half of them report they are "doing well," with another 11 percent describing themselves as "very well off." For this income class, shortage is not a daily condition that affects their day-to-day life.

While the survey explored concerns in many domains, inflation overshadowed them all. Households across all groups named price hike as their biggest economic concern. But the poor experience it with particular cruelty. Nearly two-thirds of the bottom decile name price hikes as their number one worry. It is the price of onions, of rice, of cooking oil—each hike felt in smaller portions, diluted curries, and unpaid debts at the local grocer. For the poor, it is about whether tomorrow's meal can be secured. While for the wealthier, the concern shifts towards loan repayments or capital shortages. The worries do not end there. Income drops (50.3 percent) and food insecurity (37.7 percent) weigh heavily, creating a cycle of reduced earnings and rising costs. Health adds another layer. Among the poorest households, more than half cite costs of treatment and medicine as major concerns. For many, illness is not only a health shock but a financial catastrophe. An illness or accident can mean selling livestock, pulling children from school, or falling deeper into debt.

Even social anxieties take on sharper edges in poverty. Drug abuse and juvenile crime are prominent among the poor. Together, these experiences feed an everyday pessimism that is heavier than any macroeconomic index can capture. And yet, the survey also uncovers a paradox. Even amid such hardship, 54 percent of households say they refuse to give up. This resilience and learned toughness run deep in Bangladeshi society. Among the poorest, 27.6 percent still describe their situation as "manageable," despite daily struggles. This is not naive optimism; it is the determination to endure even when the odds are stacked against them. However, resilience, though admirable, is not enough on its own. Without real support, it risks turning into quiet endurance, a silent acceptance that nothing will ever change. The mood captured in the data is thus both a warning and an opportunity. It warns that pessimism is becoming entrenched among the poor, threatening not only their well-being but the social fabric at large. Yet the same data indicates an opportunity—the resilience that people still hold can be turned into genuine confidence, but only if policies step up to meet their needs.

The message from the numbers is hard to miss. An economy cannot thrive on the optimism of a few while the majority remain weighed down by despair. The survey shows a clear divide: pessimism concentrated at the bottom, optimism clustered at the top, and a middle that is caught between cautious hope and lingering fear. If this gap is left unattended, it risks deepening inequality, turning poverty into not just a shortage of income but a shortage of hope. Households spelt out their needs—they want prices kept under control, stronger social safety nets, better education and health, and jobs for young people. These demands come from families watching inflation eat into their meals, medical costs drain their savings, and their children's futures hang in uncertainty.

The national mood can best be described as fragile resilience. Hope is still alive, but it is uneven. The danger is that pessimism will harden into disillusionment—not only with the economy but with the very idea of upward mobility. The data, thus, is not just a story of despair. It is also a call to action. Policymakers must take seriously the emotional pulse of the economy. Growth rates and fiscal charts cannot hide the lived pessimism of those struggling in shortage. To restore balance, policy must go beyond applauding resilience and create conditions where resilience is no longer the only way to survive. In the end, the real test of an economy is not in its averages, but in whether its poorest citizens can still look forward to tomorrow with hope. Right now, too many cannot, and that is a crisis graver than any fiscal deficit.

Mahjabin Rashid Lamisha is senior research assistant at Power and Participation Research Centre (PPRC).

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries, and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments