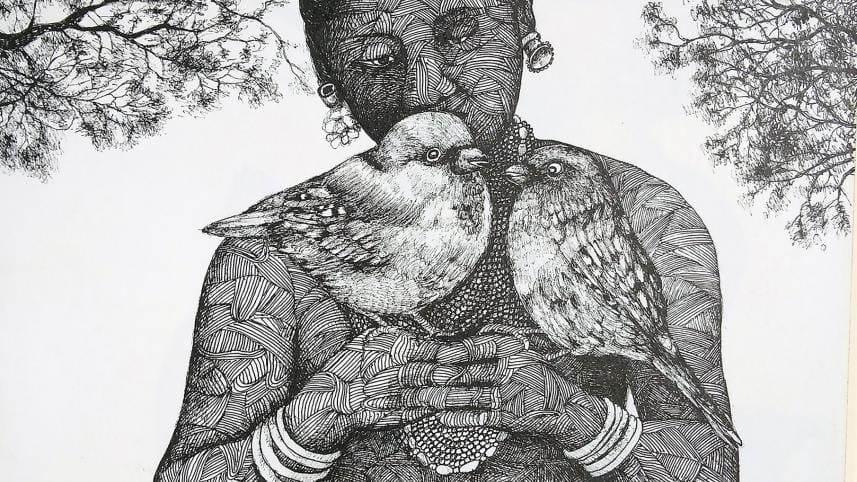

Indigenous women know how to nurture nature. We need to listen to them.

"If you enrage nature, it will repay you with sufferings and hardships," said one elderly Mro woman. Other elders nodded quietly, but their non-verbal affirmation spoke a thousand words.

SungAw, a word in Mro language, defines both nature and environment, as Mro people do not distinguish between the two. In their own way, Mro women explained that all natural elements are intrinsically and harmoniously linked to each other, and harming one element will eventually have an impact on other elements, initiating a string of causal effects that are deemed to create an imbalance in the natural world. Humans, like any other living beings, cannot escape the consequences. Driven by such experiential knowledge passed down from generation to generation, these communities have been religiously practising sustainable natural resource management, long before the scientific community came up with the term. It is now widely acknowledged around the world that Indigenous traditional knowledge is contemporary and dynamic, and is of equal value to any other form of knowledge. However, in Bangladesh, the depth of Indigenous women's understanding of the natural world and the inherent value of traditional knowledge and traditional practices are yet to be fully learnt, understood and duly recognised by the scientific community, development practitioners and policymakers alike. "Surviving with nature," – as opposed to surviving by "fighting against nature" – essentially defines this community's way of life. But the question now is, for how long?

Through a series of intergenerational dialogues between women and men at three villages of Mro communities, the richness of Indigenous traditional knowledge and the indispensable role that Indigenous women play in the preservation and transmission of traditional knowledge came to light. So did the tough challenges that women in these communities are facing while carrying out this role in a socioeconomic and political landscape that has changed drastically over the past two decades. The latter needs more attention, as the environmental violence that these communities have long been enduring exacerbates disproportionately the hardships and sufferings of Indigenous women. Environmental violence is perpetrated by politically influential non-resident entities and goons through the over-exploitation of forest produces and illegal extraction of stones from stream basins in the adjacent forests, causing severe environmental degradation in their localities.

"They have chopped off all the large trees in the forests. The streams have dried up. Let alone getting fish and crabs from those streams, we cannot even get sufficient drinking water… We have to walk half a day worth of distance just to get water during the dry season."

While both women and men are custodians of traditional knowledge, Indigenous men and women bear specific knowledge on the different aspects of daily activities and various communal affairs due to the gendered dimension of roles and responsibilities within these communities. Indigenous women, being the primary responsibility bearers in ensuring food and nutrition for their families, are the repository of knowledge on native flora and fauna, including crops, seeds and medicinal plants, seasons, weather and sustainable agricultural and foraging methods. Their knowledge is nature-based, and their practice is intrinsically linked to land, forest and every other natural element of their surroundings. Hence, when these communities experienced dispossession of land, be that of ancestral land through forceful eviction to make way for a firing range, or of Jhum land to build a popular tourist resort, or of community forest land by a non-local land-grabber, Mro women considered it as "the beginning of the end" of their survival with nature and of preserving traditional knowledge.

Constrained with limited access to land, these communities had little to no choice but to adopt non-traditional methods of agriculture, such as intense or repeated farming and cash crop cultivation, which resulted in the decline of soil fertility and yield of produce. And like a domino effect, overdependence on chemical fertilisers, replacement of native crops with hybrid varieties, increasing use of chemical pesticides to protect those novel varieties of crops followed suite. Indigenous women's knowledge on scores of native crop varieties and pest repellent plants is steadily becoming obsolete in the face of this new development.

"We used to seek forgiveness from nature if a drop of pesticide fell on our Jhum soil… We were told that without using pesticides and fertilisers, we wouldn't get a good yield of these crops. After a few years of applying those chemicals, our soil fertility and productivity have declined even more. Now fertilisers, pesticide, whatever we use, nothing works."

With the increase in using chemical pesticides and fertilisers came newer forms of health issues, including reproductive health-related complications predominantly affecting younger Indigenous women – complications that traditional medicines cannot cure. Besides, plants with medicinal properties to treat even common illnesses are becoming rare in the adjacent depleted forests. Subsequently, communities are increasingly relying on modern medicines and treatments, draining their already strained finances.

"We are falling sick more frequently. In the past, we did not need to seek medical treatment from doctors. We used to prepare our own medicine from plants that grow in the forests, and it used to cure our illnesses. Forests are gone, so are the [medicinal] plants."

There are certain foraging methods of edible and medicinal plants and wild animals from forests and waterbodies that allow natural regeneration to ensure that the stock of natural resources do not deplete, an ancient traditional practice that much of the younger generation of women has now abandoned in these villages. This course of deviation from traditional practice can be directly attributed to the fact that women, especially young women, are concerned about their safety at the hands of outsiders. The increasing presence of non-Indigenous persons/outsiders in the forests, mostly labourers and businessmen of illegal logging and stone-extracting activities, have resulted in women self-restricting their movement within a certain perimeter of the forests.

"There have been a few incidents where Bangalees chased our women with bad intentions. On each occasion, they fled leaving behind their baskets, machetes, etc… Our women gather enough courage to go to the streams and forests that are a bit far from our village."

In the past, it was strictly prohibited by custom to cultivate on the edges of streams to prevent depletion of water level, a custom that only elderly women can now recall. When cultivable land is made scarce, the yield of crops is in rapid decline and sustenance by sustainable foraging of natural resources is no longer an option, the viability of Indigenous traditional practices that are acclaimed for the conservation of environment and biodiversity for the survival of these communities is put to question by the very knowledge-holders.

What has been shared above is a glimpse of a fraction of what Indigenous traditional knowledge entails. The theme to commemorate this year's International Day of the World's Indigenous Peoples allows us to recognise and celebrate Indigenous women's rich knowledge and indispensable role in preserving and transmitting traditional knowledge. While there have been multiple calls for documentation of Indigenous traditional knowledge, which by all means is equally important, it should not be forgotten that knowledge is best preserved by practice. "What is the use of this knowledge if we are not allowed to practise?" This rhetorical question posed by a Mro woman is sufficient to provoke our thoughts on this matter. A conducive environment is needed where Indigenous women can continue practising, preserving and transmitting traditional knowledge, a precious inheritance of utmost significance in preserving the world's cultural diversities as well as in conserving biodiversity and environment. However, without protecting and ensuring the rights of Indigenous peoples to land, territory and natural resources, the inherent and ongoing challenges will continue to linger.

Based on the narratives of Mro Indigenous women documented during an intercultural research on indigenous women, traditional knowledge and environmental violence.

Rani Yan Yan is the queen of the Chakma Circle in the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments