Is harassing students a disciplinary method at universities now?

Recently, a Facebook post on the harassment of a woman and a photographer doing a photoshoot in the Curzon Hall area of Dhaka University went viral. The status described how, because the woman was wearing a "sleeveless blouse," two teachers (a woman and a man) behaved abominably with them – accusing them of taking "nude" photos and making other such hateful comments. When contacted by the media, one of the teachers involved denied the incident. But from the comments and responses on social media, it became clear that readers are of the mind that university teachers do make such comments on women's attire, and that at times, they attempt to control women's clothing and conduct and engage in behaviour that is decidedly inappropriate.

How do our highest education providers have this negative image attached to them? If we look into the reasons, we find that in recent times, quite a few student movements at universities have stemmed from the verbal and physical abuse of female students and a lack of justice surrounding these incidents. When female students have spoken out against the imposition of excessive restrictions on their freedom of movement, the university authorities have not only shown indifference – in many cases, they have made untoward comments about the protesters or said suggestive things about their characters. Female students are regularly victims of verbal abuse, and unfortunately in some cases, this abuse comes from the teachers themselves.

On top of that, the lion's share of students who also participate in this abuse are connected to the student wings of powerful political groups. Instead of being held accountable, they are given even more of a free pass. As a result, the abuse continues.

On July 17, a female student filed a complaint after five students harassed, filmed and attempted to rape her at Chittagong University. Two days went by before a written complaint was accepted. After the authorities failed to take appropriate action, protests erupted at the university. Students and teachers spoke in the media about how such incidents had occurred before on campus, but the authorities did not take the complaints into account. In previous cases, the abusers had not been punished even after being identified. In fact, they continued to receive the patronage of powerful parties and university authorities.

The mindset of the authorities became clear when, at an online discussion, CU Assistant Proctor Shahidul Alam said the place where the girl was attacked was "secluded." The presenter had to remind him that the Jamal Nazrul Islam Science Laboratory was near this location, so why should a female student not be able to go there? How can the hope of redress be anything but a distant possibility, when the person in charge of ensuring security is the one issuing separate rules for women and placing the blame on the victims?

In addition, members of the investigating committee have been found to make comments like, "If you wear clothes like this, of course they will take photos," and ask questions such as, "Why did you get out so late at night?"

Victim-blaming instead of ensuring security – we have seen this happen over and over again on different campuses. Although this unjust burden is usually foisted upon female students, male students are also sometimes victims of this.

For example, on July 25, a student named Bulbul Ahmed was knifed and killed at Shahjalal University of Science and Technology (SUST). At a dua mahfil organised for him amid student protests about campus safety, the vice-chancellor said, "Lately, there is no discipline at our campus. The way that people are freely roaming around at all hours and however they want – even we feel embarrassed when we see it."

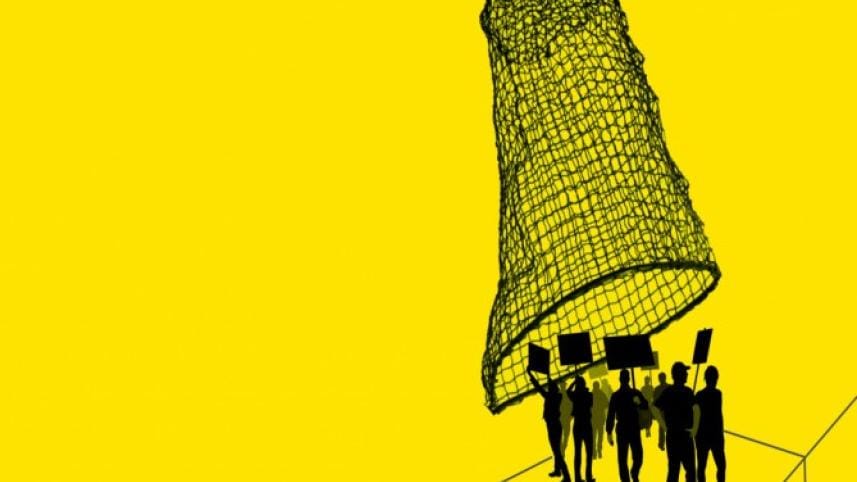

University campuses are meant to be spaces for students' freedom. The responsible teachers should feel embarrassed when the environment there does not allow for them to roam around freely. Yet, we see now that their responsibility seems to have become limited to putting down boundaries and plotting a circle of fear around ordinary students.

Readers have probably not forgotten that at the beginning of this year, a female student from SUST accused her dorm principal of misbehaving with her. Police were then called onto the campus to suppress the movement that consequently started up to demand safe female dormitories. Batons, bullets and teargas shells were used on ordinary, protesting students, as a result of which the movement turned towards demands for the VC's resignation. After almost two weeks of protests, their demands were not accepted. Instead, that the VC considers the students' just demands as wrongful opportunism, and that the female students of Jahangirnagar University are not marriageable because they do not place restrictions on movement – such comments from the SUST VC spread all over social media.

When a vice-chancellor expresses the opinion that a woman's only reason for studying at university is to eventually get married, then the word "university" is thrown into doubt altogether. By segregating female students, limiting their freedom of movement, taunting them and more, universities are being established as abuser-friendly, not student-friendly. This attitude flourishes as a result of the apathy towards implementing the High Court's guidelines (2009) on creating sexual harassment-free educational and work environments.

If we read the definition of sexual harassment written in Section 4 of the guidelines, we can come to the conclusion that oftentimes, in the name of discipline/control, teachers say things and behave in certain ways that are clearly sexual harassment. They include: i) Indecent gestures, teasing through abusive language, stalking, joking with sexual implications; and ii) Preventing participation in sports, cultural, organisational and academic activities on the grounds of sex and/or for the purpose of sexual harassment.

Under the guise of guardianship, teachers are still acting against the guidelines and reinforcing inequality. The guidelines also give clear directions on how every educational institution should create a complaint committee. However, as of the last update, not all universities have formed such committees. Even if they exist, they have not been formed according to the prescribed rules.

It is crucial that steps are taken to ensure that all university members are aware of these guidelines. This is far from the case. In fact, if you ask any student if they know where and to whom at university should they go if they face sexual harassment, almost 100 percent will respond with "no".

Whenever questions are raised regarding sexual harassment, we witness the authorities becoming concerned over the image of the university. Yet, a history of harassment and abuse also pursues and filters through to the collective memories that make up the "image" of a university. Alongside written history, these memories, passed on through oral history, eventually contribute towards a lack of progressive thought at universities.

Imagine a university where students can move around safely and where victims of sexual harassment receive justice. Wouldn't the image of such a university be even more elevated?

It often feels like universities are no longer spaces for free thought, but are working as institutions of thought control. Where control over students is maintained at a micro-level through violence and fighting forces. The apathy towards ending sexual harassment is simply a symptom of this control.

Still, I hope that I will be proven wrong.

Dr Gitiara Nasreen is a media analyst and a professor at the Department of Mass Communication and Journalism at Dhaka University. This article was translated from Bangla by Shuprova Tasneem.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments