Foreign fighters in Myanmar: Implications for the region

Al-Jazeera came out with a piece of news on May 17, titled "Western volunteers join the battle against Myanmar's military regime." The news otherwise heralds a new dimension to the three-year-old civil conflict in Myanmar. But more importantly, it sounds almost like a repetition of what happened earlier in Afghanistan, which also saw a flow of Western (and Eastern) volunteers before the United States intervened militarily, which, in the end, killed thousands of Afghans and devastated the country. However, following the military intervention, the US government spent $2.26 trillion, with the most significant portion—nearly $1 trillion—consumed by the Overseas Contingency Operations budget for the Department of Defense, mainly to benefit the country's military-industrial complex. Should the news then concern the countries in the region that something similar is in the offing in Myanmar, unless contained in its infancy?

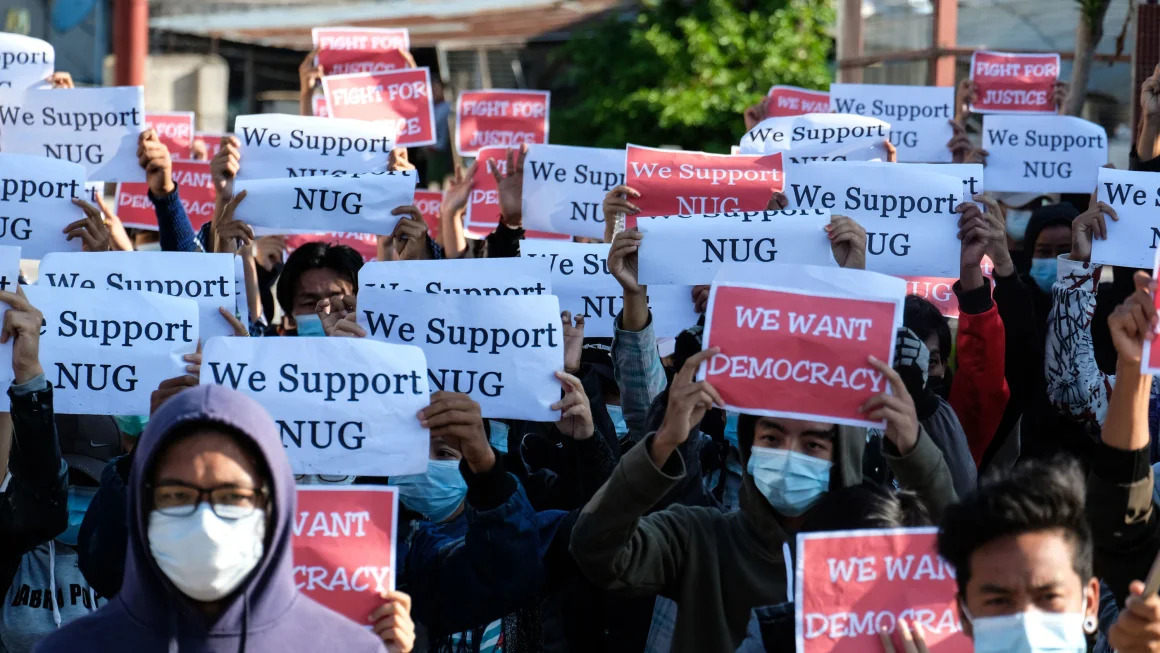

The question merits attention for two reasons. Firstly, the NUG/PDF, in its conflict against the Myanmar military or Tatmadaw, is overtly and covertly supported by the Western powers, including the US. Secondly, the Burma Act, declared by the US in April 2022, gave "discretionary authority" to the US president to interpret the act liberally, mainly when providing military aid to ethnic armed organisations (EAOs). Both reasons, in combination, probably encouraged Western volunteers to slip into Myanmar for adventure, dedication, and profit, albeit taking advantage of the US' concern for civil rights in Myanmar, notwithstanding its lopsidedness and naïveté.

A moot question then arises: how should the countries in the region respond to the arrival of foreign fighters in Myanmar, numerically insignificant though they may be at this stage? It is crucial to keep in mind here that having "foreign fighters" or mercenaries in conflict zones is not out of the norm. Instead, it has become the rule. In almost all conflict zones, whether Congo or Ukraine, mercenaries actively aid one side or the other. Apart from foreign mercenaries, there are also native mercenaries who are exploiting and profiting from the situation. One good example would be the Kuki-Chin National Front (KNF), the banned ethno-nationalist armed militant group in Bangladesh based in the Chittagong Hill Tracts. Recently, they trained and supplied weapons not to their people but to the members of Jama'atul Ansar Fil Hindal Sharqiya, an Islamist militant group.

Put differently, conflict zones, as is the case in Myanmar with the NUG/PDF and the EAOs—albeit mostly separately, fighting against the Tatmadaw—create space for the mercenaries (both local and foreign) to have a role, indeed, in the backdrop of a surge in the proliferation of arms and ammunitions. But then, without some powers' blessings, if not sponsorship, whether internal or external, it becomes almost impossible for mercenaries to become active in conflict zones. This is precisely why the KNF did not make much headway, mainly when the Bangladesh government directed its security agencies to handle the situation with zero tolerance. External sponsorship, in the case of KNF, if any, seemed dubious and half-hearted. However, having native mercenaries is the new trend, primarily because of the decline in getting foreign mercenaries and the cost of hosting such mercenaries.

The case of foreign fighters operating in Myanmar is more problematic because the members would require access through one of the five neighbouring countries, namely Bangladesh, China, India, Laos and Thailand, unless, of course, the fighters venture through the life-risking paths of the Andaman Sea and the Bay of Bengal. Not sure about Laos and Thailand because of their porous borders, but one can be sure that Bangladesh, China and India will not encourage or entertain such foreign fighters entering Myanmar through their respective territories. This is mainly because none of these three countries benefit from the civil conflicts in Myanmar. On the contrary, all three wish to see an early resolution of the civil conflicts. China providing access to "Western volunteers" is out of the question. India, too, would be opposed because of the situation in the northeast, which is already infected with various insurgency movements. Similarly, given the economic burden it is faced with as a result of the Rohingya exodus, with the goal being a quick repatriation of the latter, Bangladesh can hardly afford to support foreign fighters in Myanmar. However, this may not be the case with the Tatmadaw, not even with some international actors, particularly the US. Let me explain.

There is a general perception that humans are rational beings. While this is largely true, experience tells us that some humans, including states, are driven by what psychologists call "motivated rationality"—reason driven by motivation (Ezra Klein, Why We're Polarized, Pg 100-101). Keeping this in mind, it is worth pointing out that not all humans or states thrive on stability and peace. Some humans or states thrive on instability and conflicts. Such is the case when the reproduction basis of the state's economy depends on arms production and purchases or what is now referred to as the military-industrial complex or military-business complex. The US is a good representation of the former, and this is precisely why President Dwight Eisenhower, in his farewell speech, warned the American people of its menace, economically as well as socially.

The Myanmar military, on the other hand, is a good representation of the military-business complex. Some forms of chaos and conflicts within Myanmar rationalise its importance and presence in contradistinction from having a civil authority in power. At the same time, it is no wonder that international watchdogs have repeatedly singled out the Tatmadaw for profiting from narco-production, mainly synthetic drugs called "yaba" (or madness medicine) and its concentrated form "ice" (Imtiaz Ahmed, Myanmar, Narco-terrorism, Rohingya, and the World). In this respect, one ironically finds a commonality between the military-industrial complex of the US and the military-business complex of Tatmadaw. Both thrive on instability of some form or other.

However, contrary to the positions of the US and Myanmar, there is a commonality between Bangladesh, China and India: all aspire and thrive on stability. It is this commonality, particularly in the backdrop of civil conflicts in Myanmar and the US' declaration of the Burma Act, and now with foreign fighters in Myanmar, that creates space for reactivating the BCIM Forum for Regional Economic Cooperation, a 25-year-old entity initially called the Kunming Initiative. The BCIM Forum is indeed mandated to work on "economic cooperation," but how can states cooperate on economic issues without peace and stability in the region? The latter is a minimum condition for economic cooperation to thrive within and among states. Instability otherwise, if not contained, is bound to create greater instability, and often it becomes too late to stop the tragic consequences of such instability. There are ample examples in the world from which to take lessons. Bangladesh certainly would have an added interest in reactivating the BCIM Forum and reproducing stability, indeed, for the repatriation of the Rohingya and resolving the Rohingya crisis once and for all.

But how does one reactivate the BCIM Forum? This should be done in stages, combining Track 1 and 2 diplomacies. There are two reasons for this. Firstly, a trust deficit exists between China and India despite China being India's largest trading partner, surpassing the US in FY2023-24. The trust deficit arises primarily from territorial disputes, and the two sides remain rigid in finding solutions. There are also mindset issues, with Indian policymakers' propensity towards the West and democratic values and the Chinese policymakers' proclivity toward communism and civilisational values. Yet, both countries have gone a long way in shedding their mistrust and have started cooperating on many issues, including in the BRICS, SCO, Ukraine-Russia conflict, and de-dollarisation; even with respect to the UN voting on Myanmar, the two countries have voted identically.

Secondly, the BCIM Forum as a platform for "economic cooperation" was a non-starter. Similar was the fate of SAARC. As developing economies, protecting old markets and searching for new ones became the sole concern for policymakers in India and China. Given the size and double-digit growth of China's economy 10 years back, it was natural for India to be apprehensive of the BCIM Forum. For Bangladesh and Myanmar, it was doubly so in the backdrop of China's growth momentum and India's rising economic surge. Indeed, critical setbacks for BCIM and SAARC resulted from a predominance of economists in policymaking and an economistic or linear understanding of regional cooperation. More emphasis should have been placed on education and people-to-people exchanges to renew and alter the mindset before embarking on economic issues.

But time has changed. The conditions that fostered zero-sum competition and restricted Indo-China cooperation are no longer there. Geopolitical transformation, coupled with the fact that India's economy has gained momentum and is destined to emerge as a polar in the multipolar world, creates space for a renewed relationship between India and China. And there lies the merit of revisiting and reactivating the BCIM Forum. Given the crisis in Myanmar and how it is unfolding with speed and sophistication, the quicker the BCIM Forum is revisited and reactivated, the better the prospect of fostering stability in the region. Anything less will reproduce instability and create space for "Western volunteers" or foreign fighters, including local mercenaries, to meddle and thrive in Myanmar.

Professor Imtiaz Ahmed is executive director at the Centre for Alternatives in Dhaka, Bangladesh. He can be reached at imtiazalter@gmail.com.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments