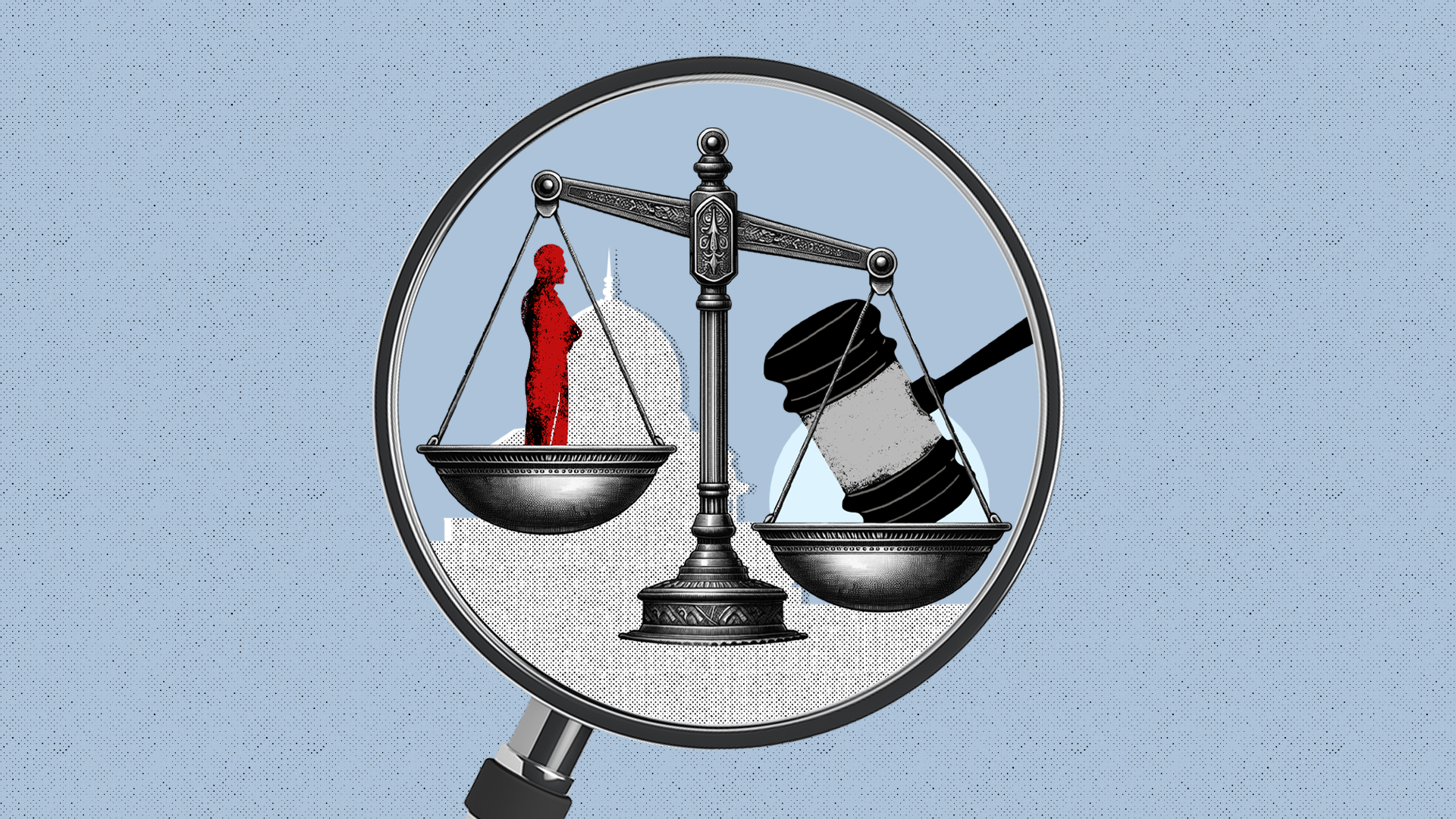

Eighteen years on, how far has judicial separation been achieved?

When Bangladesh formally separated the judiciary from the executive in November 2007, it was hailed as a historic turning point—the fulfilment of Secretary, Ministry of Finance v. Masdar Hossain(1999) and of Article 22 of the constitution. The reform seemed to promise courts free from bureaucratic control and partisan interference, empowered to function as impartial guardians of the rule of law. However, 18 years on, that promise remains only partially fulfilled. While structurally the judiciary appears independent, the lived reality tells a far more complex story. Executive influence persists, notably through appointments, postings, budget allocations, and administrative oversight. The result: a judiciary that has travelled far in form, yet not always in freedom, thus gyrating between reform and regression. A retired district judge, speaking on condition of anonymity, described it as "independence by permission"—that is, you can act freely, but only if you know where the invisible boundaries lie.

Across Bangladesh's courts, the tension is palpable. In the lower courts, many officers still operate within bureaucratic chains inherited from the old magistracy. In the higher judiciary, benches navigate the delicate balance between asserting authority and avoiding political confrontation. The rhetoric of separation remains compelling; the reality of autonomy remains unfinished.

For all its constitutional promise, judicial independence in Bangladesh has repeatedly collided with the realities of power. The mechanisms that sustain executive influence have evolved rather than disappeared. Where once magistrates served under direct bureaucratic command, today's levers lie in more subtle instruments.

One of those is placement and transfer decisions, where the Ministry of Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs continues to play a decisive role, although a separate Judicial Service Commission (JSC) was created to insulate the service from political discretion.

Budget control is another key barrier. Even after separation, the judiciary's administrative expenses continue to pass through ministerial channels. According to an evaluation, in FY2019-20, the judiciary received just 0.352 percent of the national budget.

Appointments and promotions to the higher judiciary remain politically charged. While the JSC recommends candidates, the president (on government advice) must approve; in practice, political preference often outweighs merit. Scholars note that transparency deficits here undermine public confidence and breed self-censorship among judges.

The doctrine of separation and independence was given strong articulation in the Masdar Hossain case, which held that the judicial service is "structurally distinct and separate" from the civil executive. And yet, in practice, executive influence continues. For instance, the practice of "mobile courts" (executive-magistrate-led judicial functions) still blurs the line between enforcement and adjudication, contrary to the spirit of separation.

If law is the skeleton of justice, culture is its breath. In Bangladesh's judiciary, the deeper challenge is not merely constitutional design but institutional psychology—how a generation of judges, lawyers, and court staff absorbed a culture of deference rather than assertion. The judicial service still carries the imprint of its bureaucratic past. Many officers entered under the old civil service paradigm; though rebranded, the habit of obedience remains. A senior High Court lawyer notes, "We call them judges, but we haven't retrained the reflex."

Public trust, meanwhile, oscillates between cautious respect and frustration. Surveys indicate that while citizens broadly defer to the judiciary's authority, they view it as slow, expensive, and sometimes partial. Comparative Commonwealth experience offers valuable guidance. India's judiciary, separated since the 1970s, still contends with its "collegium system," where incumbent judges of the Supreme Court of India appoint judges to its judiciary. Pakistan's judiciary has oscillated between assertion and retreat; the UK only achieved true administrative and budgetary autonomy via the Constitutional Reform Act 2005. Bangladesh lies somewhere between aspiration and inertia.

Critics argue that true judicial independence rests on three interlocking pillars: financial autonomy, transparent appointments, and administrative self-governance. Dr Kamal Hossain once described judicial independence as "the conscience of the Republic." Without institutional oxygen, that conscience struggles to breathe. While younger judges trained in a new ethos and digitalisation efforts reflect a generational shift, systemic weakness remains.

For all the rhetoric of reform, independence is not simply a structural achievement—it is a lived condition. To realise it fully, Bangladesh must move beyond symbolism by ensuring financial autonomy, transparent appointments and promotions, and institutional self-governance.

Without financial independence, autonomy remains conceptual. Therefore, the judiciary's budget should be placed under its own control, for example, via a separate judicial administrative and financial secretariat. Besides, a more open, merit-based JSC process (possibly including civil society oversight) would reduce perceptions of partisanship and elevate institutional credibility. Finally, the judiciary must administer its own transfers, training, evaluations, and discipline. A judicial council, composed of senior judges and administrators, could anchor this autonomy.

The September 2025 High Court decision restoring control to the Supreme Court represents a recent step. However, culture remains the decisive catalyst. Judges, lawyers, and officials must internalise independence not as defiance but as duty. The Bangladesh Judicial Administration Training Institute (JATI) and university partnerships need reinforcement to embed constitutional ethics and professional confidence.

The judiciary also depends on the health of a country's democratic ecosystem. When parliament weakens, media polarises, and civil society retreats, the courts are placed under existential pressure. In such contexts, the alternative to independence is executive dominance. As one retired judge observed, "A state without an independent judiciary is like a body without a spine. It can stand, but not upright."

Public trust remains the final measure. Independence must be earned through transparent judgments, timely hearings, and ethical consistency. The High Court's rulings in environmental matters, rights protections, and election oversight provide flickers of hope; however, sporadic judicial courage cannot substitute for systemic strength.

Eighteen years after formal separation, Bangladesh stands at a constitutional crossroads. The next decade will determine whether the judiciary evolves from a dependent institution to a pillar of autonomous justice. The roadmap is clear: constitutional adherence, administrative reform, and cultural renewal. What remains uncertain is whether political leaders will see independence not as a threat but as the republic's greatest safeguard.

Md. Arifujjaman is deputy solicitor (Additional District Judge) at the Solicitor Wing of the Law and Justice Division in the Ministry of Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs. He can be reached at: arifujjaman.md@gmail.com.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments