A Dhaka we’ll want to arrive at

Bangladesh is at an urban crossroads owing to a number of reasons. First, the population of the country living in urban places will be nearly 50 percent by the year 2030. What poet Jasimuddin painted in words about Bengal's agricultural ethos and rural civilisation—in those memorable lines: "maya momotaey jorajori kori"—has taken a radical turn of an urban intensity. With its fury and fantasy, Dhaka is perhaps the prime example of a city having opposite dynamics: a new reality as real as the ancient ethos. Second, at the other end, in the landscape of "maya-momota," things are also in flux. The city has arrived at this point in the form of a cell phone, in refrigerators sold out of rural stores, and in remittances arriving from various regions of the world. There is much to think about in terms of the future of our "timeless" villages, as they transform to the tune of the times. Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina's call for bringing the city to the village is significant in a way, but it has not been adequately expanded—conceptually and theoretically—besides some bureaucratic exercises.

Dhaka, as the prime city, is undergoing some real changes, and perhaps, at last, with some lasting impacts towards having an improved and measurable quality of life. Dhaka is now a showcase for new, and necessary, urban infrastructures that include, above all, mass transit systems (the MRT is one). In a 2010 article in this newspaper, offering a solution to Dhaka's transportation anguish, I wrote: "Mass transit! Mass transit!! Mass transit!!!" With the first MRT line in place, and more on the way, it is for the first time a government has given proper and adequate attention to the most urgent issue of the city: mass transportation. In the meantime, the urban discourse has been extended with the new Detailed Area Plan (DAP), which is unlike previous plans that lacked imagination in terms of recognising the intensity of issues for a city like Dhaka. Despite criticism from some quarters, I maintain that the DAP 2022-2035 presents propositions that are timely for a furiously transforming city as Dhaka.

Yet, yet… the city, the one that we want to arrive at, remains illusory. It appears we are still caught in a conundrum between the city and the village, between the pressures of the economy and the obligations to ecology, and between full-fledged planning and laissez faire conditions. We are still unable to imagine the city we want to have.

In times of such conundrum, I have always turned to the master Italian storyteller Italo Calvino—a great articulator of the magic of the city. In the book Invisible Cities, Calvino talks about an allegorical arrival at the city: There is a city by the sea, writes Calvino in one of the chapters, and depending on whether you arrive by land or by sea, you will find a different city. In our determination to arrive at the city called Dhaka, we have not quite figured out which direction to take, or what urban philosophy or principle to adopt. This is not the first time I have enumerated the gateways or propositions for arriving at a "good" city; I have done it many times and I am doing it again, here. Repetition makes for a rallying call.

Enriching the public realm

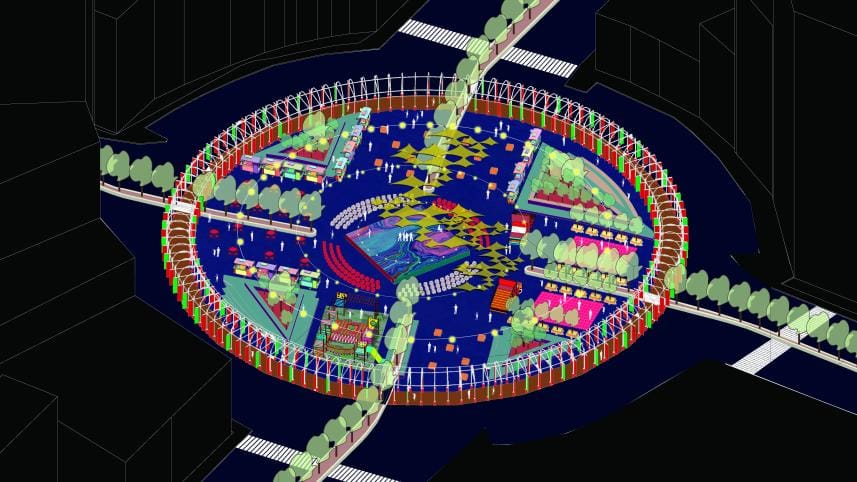

A "good" city, the place we want to arrive at, is hard to define. And yet, being liveable, healthy, and equitable are some of its defining parameters. Showcasing snazzy apartment buildings, showy corporate offices, and spectacular structures is all part of a fiction in making a better and equitable city. As I keep saying, architects make stunning buildings, but the city is going to hell. It seems we have a problem in dealing with the larger scale of the urban and the regional. At a scale beyond the building, the first task is to enrich the public realm, and whatever names it goes by: commons or "gono porishor."

Cities need—and Dhaka needs dearly—various forms of public and civic places that will provide the essential experiential spaces where citizens can thrive in an urban milieu. Unlike individual buildings which are mostly exclusive, public spaces offer an equalitarian experience that any and all can participate in. Such spaces signify "commons" or outdoor living rooms that stage the city's life and energy, and make the city inviting for everyone. If a plan for Dhaka aspires to be socially inclusive and humanistic, it should begin with generous attention given to creating public spaces at all scales, from the city to the neighbourhood and even the corner of a street. And that is my first proposition towards making a good city.

Nearly all major cities of the world, especially in response to the pandemic, have focused their attention on the significance of public spaces. Many cities in the US have adopted what is known as "open, slow, or shared" streets in which the presence of the automobile has been curtailed or controlled to provide mini open-air public spaces. The mayor of Paris, Anne Hidalgo, has unfurled the idea of the 15-minute city, in which most needs of the people can be catered to within a 15-minute walkable neighbourhood.

Dhaka badly needs a walkability plan

A second proposition integral to the public realm is the making of a walkable city. If open and public places define the civic realm of a city, sidewalks or footpaths are a necessary component of that network—they determine the civility and humanity of a city. This is particularly critical for Dhaka, where more than half of the population walks. Such urban pedestrian systems as boulevards, promenades, river walks, or simple sidewalks, that are the hallmark of all liveable cities, are, for the most part, non-existent in Dhaka. And if they do exist, they hardly create a legible and efficient network. Primarily constructed as cover for drains, most footpaths are ironically unwalkable: they are broken into segments, are obscenely high (some requiring steps for one to climb onto them) and, when they do exist, they are often unsafe to walk on. No wonder people walk on vehicular roads, even at the risk of being run over.

In our cultural schema, we prioritise the movement of motorised vehicles, and place the pedestrian at the lowest level of all policymaking and infrastructure planning. Where once the pedestrian ruled, and the city was a place for walking and meandering, and enjoying its footpaths, riverbanks and public spaces, now the automobile dictates the terms of organising the city. We make roads for cars, and direct all major investments—elevated roads, flyovers, U-loops, and ever-wider roads (by chipping away at footpaths)—towards the promise of uninterrupted vehicular movement, all while cornering the pedestrian to the shrinking edge of the road.

A good city is, above all, a walkable city—this is an axiomatic truth propagated by ardent lovers of the city, from the poet Baudelaire to biologist-planner Patrick Geddes, and from urban activist Jane Jacobs to sociologist Henri Lefebvre. Our most intimate engagement with the city is in walking. I describe this phenomenon as "metrophilia," a love of the city found by walking it.

A walking environment should be the number-one priority in any transport or urban planning, which has not yet happened in Dhaka. A walking infrastructure is critical to the success of MRT and BRT lines. It is expected, as is the case for any city with successful mass transit, that people will access the stations by walking, not by driving there. A walking network is also a cue for making neighbourhoods lively.

Transport infrastructure as the key to development

Transport vitality is the single-most effective impetus for a better Dhaka. It is not only the carrier of peoples but a leverage for urban development. We are inspired to see that transport infrastructure has been a major investment focus of the government. Even though slightly belated, mass rapid transport (MRT) lines will finally catapult Dhaka city into the 21st century.

Considering the upcoming MRT and BRT systems, a transit-oriented development (TOD) is a perfect opportunity for radically restructuring Dhaka. This is the third proposition. MRT is not only a transport instrument for moving people, but could be a development catalyst in which each station becomes an opportunity for creating concentrated urban hubs or neighbourhoods, and the transit line itself could be a development corridor.

We could look at Tokyo, Singapore, and Bangkok, where stations in transport lines are planned as urban hubs with dense civic and commercial consequences. In Tokyo, the city has literally grown around those hubs, especially with the famed Shinjuku and Shibuya stations. Instead of a conventional masterplan, The Bangkok Plan of the 1980s focused on developing the city around station-based hubs. I would suggest the MRT and TOD planners in Dhaka look into such models, and in any future revision of the DAP, consider higher floor area ratio (FAR) for an area around the stations and along the artery. With taller mixed-use buildings around the stations, high density habitats will ease commuting time, create greater ridership, and more sustainable urban living.

In creating new types of neighbourhoods, new types of housing models are necessary, whether in the form of consolidated housing, social housing, affordable housing, or group housing. As of yet, none of these are reflected in the vocabulary of Dhaka's builders, including the government agencies, private developers, architects, and planners. What the DAP 2035 has presented as "block housing" is a precursor to the formation of the above housing typologies.

Water flow as a basis for planning cities

This is perhaps my most earnest proposition. Most of the challenges of the future will be environmental, in which the proliferation and expansion of cities will be the most critical topic. What will be the nature of future cities and towns? How will the expanding city impact the landscape beyond the city? How will villages transform? Will the future city and village merge into a third settlement type? The biggest urban question for Bangladesh remains this: how to arrive at a junction that mediates between the enormity of ecology/hydrology and the development propulsions of economy? In short, ecology and economy remain at loggerheads with each other. The issues and requirements of climate change are also linked here. To arrive at such a junction, we need imaginative approaches to urban thinking.

In a place where water is the fundament, and hydrological planning a prerequisite for any development, we have instead opted for a dry ideology. The result: buildings are built by filling in wetlands. Rivers and canals are encroached upon in the name of industrialisation. Water bodies and channels are polluted indiscriminately. It appears that nature and development—prokriti and progoti—face each other in a tragic opposition. In order to create a balance among progress, nature, and climate change, a new equation is necessary. A newer way of thinking about life and living that is commensurate with our landscape is required. Instead of conventional practices of land-filling and embanking, we have to think of cities in a delta with new mantras: "let it flood" and "let it flow."

Life in Bangladesh would be impossible without considering water and its flows. This has become more urgent in the time of climate change. Urban forms will have to include rivers, canals, wetlands, and paddy fields in their formations. In adapting to diverse changes, from the environment to climate, and from the technological to the migrational, Bangladesh can still arrive at novel and humane cities. We have to develop our own model of the city; the place we want to arrive at.

Kazi Khaleed Ashraf is an architect, urbanist, and writer who directs the Bengal Institute for Architecture, Landscapes and Settlements.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments