Can Dhaka evolve from decades of chaos and mismanagement?

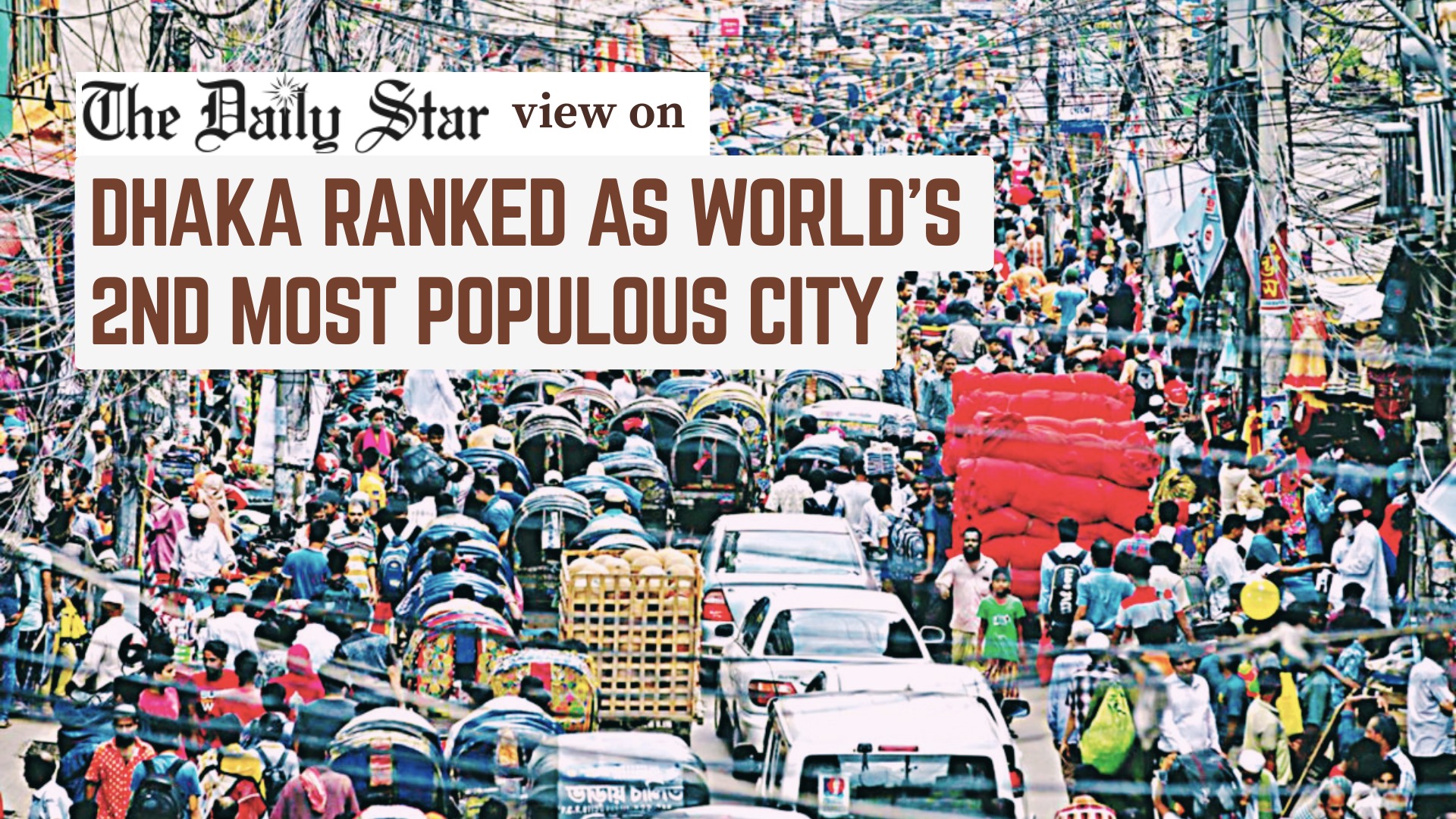

The morning sun in Dhaka struggles to pierce the haze, casting a pale glow on a city in motion and in crisis. On the streets, the air is thick enough to taste a metallic mix of dust and exhaust that clings to the back of the throat. This is not just poor air quality—one of the worst in the world, silently stealing nearly seven years from the average resident's life expectancy; the cacophony in the city is a constant assault. Traffic noise reaches 119 decibels, a level comparable to a rock concert that makes civil conversation a struggle and restful sleep a luxury. This is the sensory reality of Dhaka in 2025—a metropolis now designated the world's second-largest city, home to nearly four crore people. This designation by the United Nations is not a badge of honour for us; it is just an acknowledgement of Dhaka's current reality—a city built by relentless, unplanned accretion, not by design. We are living with the consequences of decades of reactive governance, and the crisis has become an existential threat to our nation's economic and environmental future.

Dhaka's suffocating reality stems directly from policy failures that treated urban planning as an obstacle, not a necessity. The relaxation of building regulations that began decades ago culminated in the introduction of Floor Area Ratio (FAR) regulations in 2008, which created a perfect storm of vertical congestion without the corresponding infrastructure to support it. The result is a city of brutal contrasts. While global hubs like Tokyo thrive with an average density of 15,700 people per square kilometre, Dhaka's densest wards are crushing under the weight of 150,000 people per square kilometre. The problem is not the number of people, but the failure to distribute resources equitably. This failure was compounded when FAR limits were almost doubled in several residential areas, allowing towers to rise from alleys too narrow for a fire truck to pass.

The cost of this chaos is quantified in brutal metrics that should shock our collective conscience. Our economy bleeds $4.4 billion annually from traffic congestion alone, a massive drain on national productivity that the World Bank has repeatedly flagged. In global liveability rankings, our capital sits near the very bottom, at 171st out of 173 cities, barely surpassing active war zones. Our natural lifeblood, the rivers, are poisoned. The Buriganga's average dissolved oxygen levels have plummeted to zero in dry seasons, far below the 6.5 milligrams per litre required for a healthy aquatic ecosystem, symbolising a city choking on its own waste. The relentless centralisation of the nation's administration, commerce, and hope into one overwhelmed metropolis has created what urban expert Adnan Morshed calls a state of gadagadi—a phenomenon of people living in extreme congestion without the most basic urban services.

The solution, however, is not to resist density but to transform it from a burden into our greatest asset. The blueprint exists in cities that have turned similar challenges into triumphs. Tokyo and Hong Kong demonstrate that high population concentrations can produce remarkable economic dynamism and sustainability when properly managed. Tokyo's wards, despite their densities, remain highly liveable through meticulous planning, efficient mobility, and an equitable distribution of amenities. This is the model of "good density"—a revolutionary framework for Dhaka where people live in compact, affordable homes with easy access to schools, clinics, work, and parks, all within a comfortable walking distance. This approach, a form of tactical urbanism, reduces the city's carbon footprint by minimising cross-city movements and creating self-sufficient communities.

Transforming this vision into reality demands more than technical master plans; it requires a moon-shot level of political will and a fundamental rethinking of urban governance. The World Bank has explicitly called on Bangladesh to address "planned urbanisation" as a core reform to sustain growth and job creation. This begins with reversing the perverse incentive structures that make violating rules more profitable than complying with them. We must champion ward-based development, ensuring each of Dhaka's 129 wards becomes a self-contained unit with equitable access to parks, schools, and markets. Our promising metro rail system must be integrated with protected walkways and cycling lanes, recognising that the majority of Dhaka's commuters travel on foot. Simultaneously, we must launch an environmental resurrection, restoring the blue network of canals and rivers that once defined this city, to combat the urban heat island effect that has seen temperatures in many areas soar to a blistering 40.7 degrees Celsius.

The International Monetary Fund acknowledges Bangladesh's "ambitious goals for achieving environmentally sustainable economic growth," but warns that "further efforts are needed to rapidly scale up resources." This is the defining challenge of our generation. The cost of fixing Dhaka today, while immense, will be a mere fraction of the catastrophic economic, social, and environmental costs we will inevitably face if we fail to act. We must immediately protect our natural systems, halt the filling of waterways, and launch an emergency programme to restore the rivers surrounding Dhaka. We must implement transit-oriented development that prioritises people over vehicles. And crucially, we must embrace genuine participatory governance, building public trust by giving communities a direct voice in the decisions that shape their neighbourhoods. The United Nations reminds us that inclusive urbanisation can unlock transformative pathways for climate action and economic growth. We can continue to be victims of a chaotic fate of our own doing, or we can become the architects of a livable, sustainable, and economically vibrant city worthy of its people. The survival of our nation's ambition depends on the choice we make today.

Zakir Kibria is a Bangladeshi writer, policy analyst and entrepreneur based in Kathmandu. He can be reached at zk@krishikaaj.com.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries, and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments