Bangladesh needs revolutionary changes to deal with floods

Much of eastern Bangladesh is under water right now. The flood-affected areas extend from Sylhet in the north through Cumilla, Feni and Noakhali to Cox's Bazar in the south. People need help and it is encouraging to see that the students and young people, together with others, have engaged themselves with the relief work.

Global, regional, and national drivers have all combined to create the current flood disaster. The global driver is embodied by climate change, one of whose effects is the increase the frequency, scope, and intensity of extreme weather events, including untimely and excessive rainfall. The main cause of the ongoing flooding is excessive rainfall in India's Tripura state as well as in Bangladesh. Climate change is also causing sea-level rise, which slows down the passage of river water to the sea, thus aggravating and prolonging flooding. In the coming days, this may play a significant role in Feni and Noakhali districts, which are close to the sea.

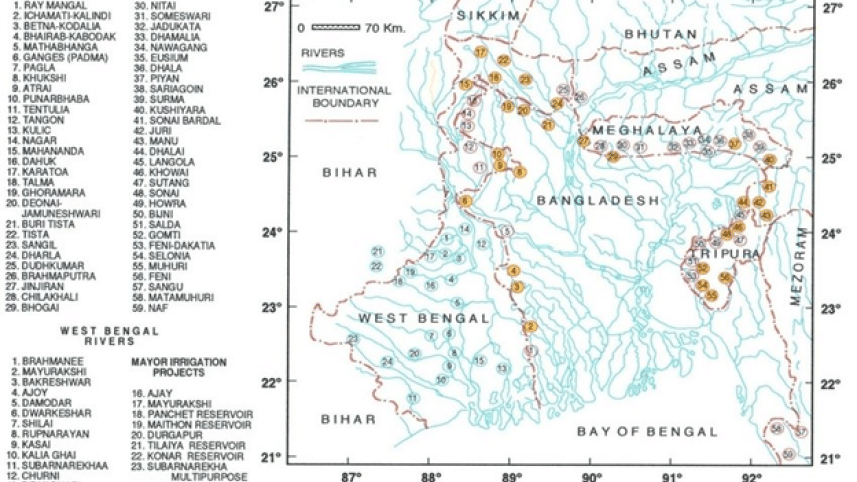

The regional drivers are rooted in the fact that about 90 percent of the water that flows through Bangladesh's rivers originate outside—mostly in India. Almost all the water from the torrential rain that fell in Tripura (about 330mm in just two days of August 20-21) came to Bangladesh through Gomati, Khowai, Feni, Muhuri, Manu and other rivers and added to the rainwater that fell inside Bangladesh to cause the flooding. Some water also came from the reservoir (about 60 sq-km) of the 30-metre-tall Dumboor Dam that India has constructed on the Gomati River, about 120 kilometres from the Bangladesh border. Some reports suggest that gates of this reservoir were deliberately opened to release water. The Indian high commissioner to Bangladesh, however, maintained that the release was an automatic process, triggered by the reservoir's water level exceeding a certain limit. Be that as it may, there is no doubt that water, released from the reservoir, added to the volume of water that caused the flooding.

This is another example of the increasingly man-made character of flooding in Bangladesh, i.e. flooding caused or aggravated by decisions made by the operators of the dams and barrages that India has built on almost all rivers that it shares with Bangladesh. Consequently, India's river intervening structures not only reduce dry season flow in Bangladesh's rivers, but have also become a source of untimely and more severe floods. This has particularly been the case with the Teesta basin in Bangladesh, where residents have witnessed seven such floods in a recent year alone.

It is well-known that the previous government failed miserably in protecting Bangladesh's right on its rivers. For political reasons, it approached India as a supplicant and allowed it to do whatever it wanted with the rivers, with little resistance offered. Yet, just as Bangladesh depends on India for river flows, India also depends on Bangladesh for easy access to its seven northeastern states. In 2013, the Bangladesh Environment Network (BEN) put forward the "transit in exchange for rivers" formula, under which India would restore the natural flows of the shared rivers and, in exchange, Bangladesh would grant India transit and transshipment facilities to access its northeastern states. BAPA and BEN have also been urging the Bangladesh government to sign the 1997 UN Convention on the Law of the Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses, which forbids a country from intervening in shared rivers without the consent of other co-riparian countries. We hope that the interim government, with a renowned environmentalist in charge of the water ministry, will lose no time to sign the 1997 UN convention and use it in negotiations with India under the "transit in exchange for rivers" framework.

Of course, national (domestic) drivers are the ones over which Bangladesh has the greatest control. In this regard, the current floods further vindicate the necessity of moving away from the Cordon approach towards the rivers, which Bangladesh has been following since the 1950s, to the Open approach. While the former approach strives to constrict rivers (by constructing embankments) to their channels only, the latter one allows rivers to overflow onto the floodplains during the rainy season. This allows floodplains to serve as an additional passage for river water to move to the sea and for sediment to be deposited on floodplains, raising their elevation. Under the Cordon approach, the opposite happens: the elevation of floodplains cannot increase, while sediment gets deposited on river beds, raising their level. Consequently, after some time, the riverbed reaches an elevation that is higher than that of the adjoining floodplains. The Gomati River embankment illustrates this perverse outcome. In many places of Cumilla district, the riverbed has a higher elevation. One can easily imagine the catastrophe that can result if the embankment breaches in such places—as seen when the embankment collapsed in the Burichang upazila in the early hours of yesterday, flooding several villages. About five lakh people are now marooned in the area.

Once the immediate tasks related to the relief and rehabilitation necessitated by the floods are dealt with, the interim government will have to make a clean break from the Cordon approach and make the Open approach the official policy. The mindset of the personnel in all water-related agencies has to change. Instead of a money-making business of politicians, bureaucrats, engineers, and contractors, water development has to be about the noble business of serving people. Embankments have to be gradually opened up, the obstructions on the floodplains have to be removed, and the sediment has to be used to raise the ground of villages and towns. All roads in floodplains have to be built on pillars. In short, revolutionary changes have to be brought about in the water sector of the country. That is the only way we will be able to protect the people from the recurring pain and suffering caused by floods. That is how we will be able to equip Bangladesh and its people to confront the impact of climate change.

Dr S Nazrul Islam is the founder of Bangladesh Environment Network (BEN) and the initiator and vice-president of Bangladesh Poribesh Andolon (BAPA). He is also the former chief of development research at the United Nations and a visiting professor at the Asian Growth Research Institute (AGI) based in Japan.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments