As the world changes, so must our English education

Foreign Adviser M Touhid Hossain, while speaking at a recent event, shared his personal observations on what he called "educational apartheid." In his professional experience across various countries, he noticed that a lack of English proficiency forces many Bangladeshi migrant workers into menial jobs with low wages. In some cases, workers from our neighbouring countries earn three times more than ours. This highlights a key truth: the global economy values English as a skill of high currency. Yet, despite over 12 years of English language training, our schooling system fails to equip the majority of citizens with this essential skill. As a literature teacher at the tertiary level, I often face questions from employers and civil society members. I am not a language policymaker nor a materials developer. Still, I cannot ignore my responsibility when a coaching centre boasts that a six-month course can offer more valuable skills than a four-year degree in English.

The idea arose when British Council, as a sponsor of a two-day international conference on transforming English language teaching, came to Dhaka University. Its business director mentioned a recent survey result: 34 percent of employers in Bangladesh prioritise English skills when hiring. This statistic underlines the widening gap between the job market's demands and the skills our education system provides. Given that English is the primary language of ICT and is spoken by 1.5 billion people worldwide, proficiency in English is often the deciding factor between securing a well-paying job or remaining in low-wage labour. It is disheartening that our workers struggle not due to a lack of talent but because they lack the language skills necessary to seize opportunities. For the same reason, there are thousands of top-level managers from India and Sri Lanka working in our factories and business outlets.

This linguistic gap titillates donors and foreign organisations to promise modules and aptitude tests. Traditionally, they have been successful in selling such programmes easily to opportunist bureaucrats or corrupt political leaders through their imported experts. Expats often supervise the preparation of materials for our national curriculum, promoting models like communicative English and experiential learning. However, when we compare textbooks for our local students with those from native English-speaking countries, the discrepancy is glaring. Our curriculum has been systematically dumbed down.

Conversely, when our students aspire to higher education abroad, English language proficiency requirements become increasingly stringent. So they must enrol in a coaching programme and pay hefty test fees multiple times to demonstrate their linguistic competence. All for money. Do foreign missions have the authority to engage in commercial activities? Do these foreign agencies pay taxes? Curious minds want to know.

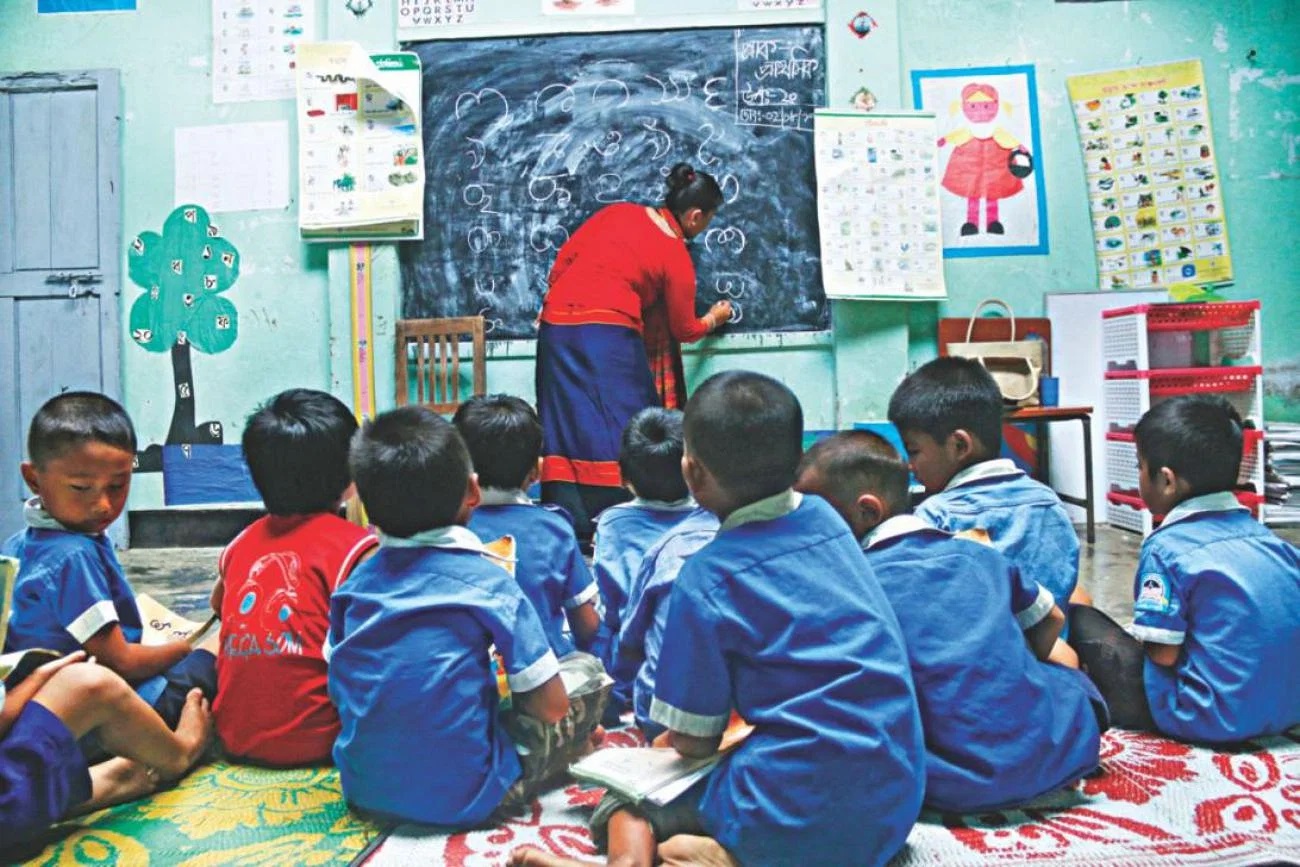

In a political climate demanding change, we must ensure that graduates from all education streams—Bangla medium, English medium and madrasa—are prepared for the challenges of a globalised world. English-medium graduates often secure better jobs and adapt more easily to professional settings and higher education. However, their advantage is not just linguistic; their education also enhances cognitive skills. On the other hand, Bangla-medium graduates often struggle to express themselves in job interviews or professional discussions, especially if it involves speaking English. This disparity reflects not only a gap in access but also a failure in our educational priorities.

The idea that you do not internalise knowledge when you memorise is partly true. To avoid such possibilities, our English language texts in communicative and creative classrooms offer chunks of information. This aligns with the colonial project of limiting education to the native population. The colonial powers wanted us to serve as civil servants or managers, never as masters of our own fate. It's a shame that, as an independent nation for 53 years, we still rely on foreign experts or imported ideas. We have failed to identify our own needs and embrace the English language that is crucial for our advancement.

Instead, we have a flurry of excuses: not enough qualified teachers, insufficient salaries, outdated textbooks, lack of incentives or motivations, etc. We have no desire to invest in our teachers or reading materials. That does not stop our bureaucrats and experts from travelling abroad to gain "first-hand experience" of native English language settings and then proposing ambitious curricula and models. This self-defeating logic ensures that our students remain unprepared for the demands of the globalised world, perpetuating a cycle of mediocrity.

The issue is even more glaring when we consider the success of private language institutes, which teach languages like Chinese, German, and French in relatively short periods. If these institutes can achieve results in months, why can't our schools teach English effectively over a decade? The answer lies in our collective ambivalence toward English. As a nation, we struggle to reconcile our commitment to the mother tongue with our recognition of English as a global necessity. The bilingual English textbooks prepared by the National Curriculum and Textbook Board (NCTB) exemplify this ambivalence, failing to provide an immersive language experience, leaving students neither fluent in English nor confident in Bangla.

Some may claim that emphasising English perpetuates colonial legacies, but this perspective misses a crucial point: true decolonisation requires the tools to challenge and dismantle colonial ideas. English, paradoxically, is one such tool. In a world where English dominates international discourse, media, and the internet, not knowing the language handicaps us. It's not just about economic opportunities—it's about representation, identity, and the ability to shape our own narrative on the global stage.

For example, Bangladeshi cricket fans often struggle to respond to taunts from opponents because they lack the language skills to retort. Similarly, when foreign media portray Bangladesh negatively, we lack the linguistic capital to counter these narratives. English is more than a language of commerce; it is the language of power, and without it, we remain voiceless in international conversations.

The younger generation, born into the age of the internet, instinctively understands this. For them, English is not a colonial relic but a necessity. It is the language of the internet, social media, and global culture. Coding, online learning, and digital entrepreneurship—all require proficiency in English. So, denying young people the opportunity to master this language is not just an oversight—it is a crime.

The failure of our education system to teach English effectively is symptomatic of deeper systemic issues. Rather than confronting the root causes, we have allowed a culture of complacency to take hold. The solution is not to lower standards but to raise our expectations. We need to invest in teacher training programmes that produce skilled educators who understand not just the mechanics of English but its cultural and professional significance. We must design curricula that prioritise real-world communication skills and critical thinking over rote memorisation. And, most importantly, we need to listen to the voices of young people who are eager to learn and grow.

Dr Shamsad Mortuza is professor of English at Dhaka University.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments