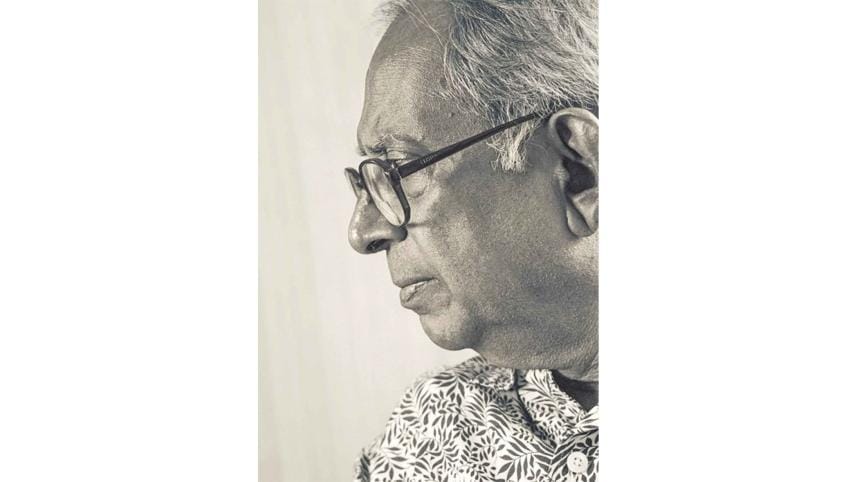

Farewell, My Friend

My first meeting with Mohiuddin Ahmed was in 1956, at a dinner in his brother's house. His brother, Kabir Ahmed, was what in Bangla we call the "bhaira bhai" of SAM Khan, my father's colleague in the civil service, and the friendship of the two families extended to include him. It was not really a family dinner and I still do not know why I was invited and not my brother, who was closer in age to Mohiuddin. Among all the grown-ups, I felt quite out of place. And then this stripling came up to me and asked whether I would like to see his brother's art collection.

There were no paintings in our house, and my brother's interest in art—nurtured by Munni aunty, who later became Mohiuddin's bhabi—was frowned upon by my stern mother.

I was not interested in seeing paintings, but it was a relief to leave the grown-ups so I took up the offer and went off to see the paintings—some of them by his bhabi. I do not remember the names of the artists or even the paintings that I saw. Through the home education that my brother and I had got before we went to Viqarunnisa and St Gregory's, we had been introduced to many European artists as part of an art appreciation course. But these paintings were nothing like the ones I had seen in our books.

When I left that evening, little did I know that the thin teenager would, in later years, become my friend, publisher, and mentor. And little did he know either that evening that he would become one of Bangladesh's most respected publishers, publishing quality books in different genres.

My second meeting with Mohiuddin—I never got to call him by his pet name Moin, which his friends Ameena Saiyid and Urvashi Butalia, who had worked with him at the Oxford University Press (OUP), did—was in Karachi, 1971. It was again at a dinner. The late Ejazul Huq, better known as Emran to his friends, suggested one evening that if I was free, I might want to meet some friends of his at the house of Martin Pick, who was working at OUP. There would be other Bengalis as well. In 1971, surrounded by family who did not quite understand the reality of what was happening in East Pakistan, it would be a relief to meet Bengalis.

One of the Bengalis there was Mohiuddin Ahmed, at the time Martin's colleague at OUP, Karachi. I do not remember what else we talked about, but I still remember that he showed me an alphabet book by Dr Seuss. "Try to write something like this," he said. No, I never tried to write like Dr Seuss, but I did try to get Dr Seuss's wild and crazy books for my sons.

I returned to East Pakistan in October and lost touch with Mohiuddin. And then, one day, shortly after Bangladesh had become independent, he contacted me. He had started University Press and needed some help with a manuscript he was interested in. What was I supposed to do? Be a reader. Check content errors, make sure there were no discrepancies, and correct language mistakes. Comment on the overall quality of the book. "But I know nothing about law," I said, on seeing the manuscript. And though I had by that time had an article published in "Dacca University Studies", I had no idea what proofreading entailed. He showed me the most common marks I needed to know and I was off. Slightly familiar with footnotes and endnotes, I had no idea that the discipline of law had a different system of documentation.

Mohiuddin passed on many manuscripts to me to review and edit. Apart from content and language errors, he also asked me to check if there was anything libellous in a manuscript, anything for which a publisher might get into trouble. He often went over a passage with me, not wanting to distort what the writer had said but trying to rephrase the passage so that neither writer nor publisher would get into trouble.

In 1993, Mohiuddin Ahmed became my publisher when he published the revised edition of "The Art of Kantha Embroidery". The next year, the University Press Limited (UPL) brought out "Princess Kalabati and Other Tales". "It would be nice," I told him casually one day, "if the book were illustrated by a young person." He took me seriously and got his daughter Shamarukh to illustrate the book, which she did beautifully. He went on to publish several of my books: a book on Partition novels, another on rickshaws and rickshawallahs, anthologies of translated Bangladeshi writings, and even a culinary book (he was just in the process of accepting an edition of Siddika Kabir's book in English). As a writer, I learned how particular he was about sending annual accounts to his writers of books sold, followed by a royalty cheque a few months later (Bangla Academy pays a lump sum after a book is published, but many other publishers—some quite renowned in Bangladesh—do not provide any account of books sold, not to late alone royalty). As an editor, I learned the absolute necessity of getting copyright clearance from authors and translators.

Did Mohiuddin publish everything I offered him? No. There was a book of political essays he rejected outright. The rejection made no difference in our relationship. I respected his judgment. The essays were never published as a book. But another book which he rejected—Syed Waliullah's "Tree Without Roots", which had been out of print for decades—did not get discarded.

Mohiuddin had often suggested to Firdous Azim and me that we start an imprint like Kali for Women. He would assist us, even distribute the books for us. Though Firdous and I had even had the name of the imprint and did bring out one book together under that name, we never got to start a women's publication house. Persuaded by Syed Waliullah's cousin, who looked after his literary interests in Bangladesh, and accepting the offer that Mohiuddin had earlier made to Firdous and me, I took up the task of publishing the book—as well as other books by Syed Waliullah and others. And he did give me all the help he could.

He explained to me how to calculate the retail price of a book. He taught me what a page should look like, using a scale to make things clear. He told me about the importance of "white space". And, true to his promise, UPL distributed my publications. Afterwards, he told me that he regretted my becoming a publisher, as I had no time to read manuscripts for him.

Mohiuddin had become a publisher after undergoing rigorous training at the OUP at Oxford. He had been set to work at the press, and so had both theoretical and practical knowledge of putting a book together. How I wish that he had written a book to guide other publishers!

The onset of Parkinson's about 20 years ago gradually slowed him down. He would still be found visiting the Ekushey Boi Mela in his wheelchair, at the occasional seminar and conference, at a book launch. But he stopped going to the old office at Motijheel where his friends or writers would gather at about lunch time. He always had enough lunch to share with two others—a simple lunch of vegetables, daal, and chapatis of brown atta. If more people dropped in than he had food for, he would immediately order naan and tikka from a nearby café.

The last few years, he had to spend more and more time at home. The commute to Motijheel was too long. The new office on Pragati Sarani—which his daughter Mahrukh Mohiuddin had set up so that he could have his office there—had been badly damaged by a fire and became unusable. He also had to devote a lot of time to physiotherapy. Busy with other things, I could only visit him occasionally, always remembering to pick up lemon tarts which we enjoyed together with tea and other snacks that had been prepared at home.

In March last year, Covid put an end to those occasional visits. I missed those visits. I wondered how he was coping. Then I learned that he had developed Covid. I was worried, but he returned home. However, this last time, when he went to the hospital, he did not return. When he passed away on June 22, I could not go to see him. I myself was unwell. All I could do was sit at home and remember a friend whom I had known for 65 years, a friend who had become my publisher and a publisher to the nation, who had been honoured by the community of publishers as "Publisher Emeritus"—a great man who had by his willpower and determination tried to make Bangladeshi publishing professional and ethical. Rest in peace, my friend.

Niaz Zaman is an academic, writer and publisher.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments