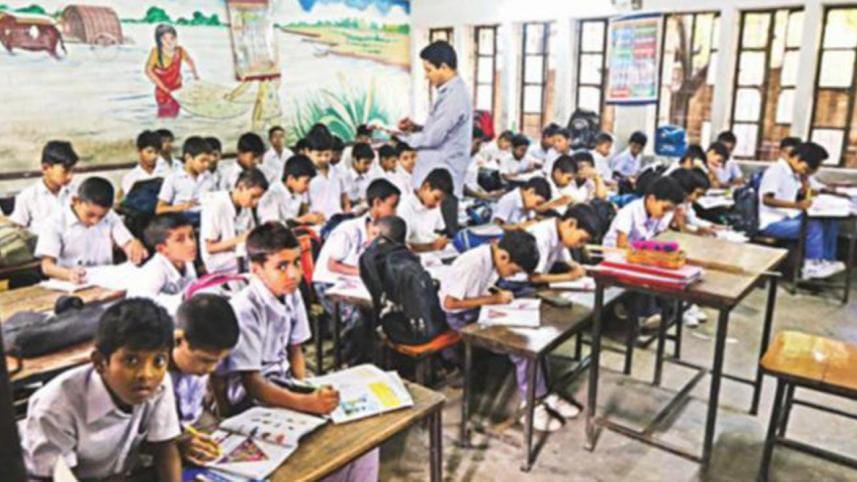

Our children are in school, but can they read?

Bangladesh can celebrate the International Literacy Day with pride. Since 2000, we have significantly increased enrolment and now nearly all children of an age to be in an early primary grade are in school. Everyone—parents, teachers, officials and political leaders—can take credit for this achievement. But enrolment is not enough. Can our children read?

Bangladesh is unfortunately a major contributor to the global total of some 250 million children who cannot read. Over the last two decades, all governments in Bangladesh have given education the highest priority in planning and budgeting exercises. Despite our efforts, adult literacy hovers around 60 percent, and this includes Bangladeshis whose level of literacy is minimal. They can write their names perhaps, but not much more. Using both national and local surveys, assessments of primary students indicate that at grade five no more than one quarter of children can reasonably be classified as able to read "at grade level."

Unfortunately, the country's education officials seem content to continue "business as usual." Given these assessments, however, this is not a time for business as usual.

We should not try to make the problem disappear by adopting an unrealistically low benchmark for literacy. Proven early grade reading interventions are available to tackle reading problems. Literacy is ideally conceived as a continuum—from the ability to read road signs in Dhaka to the ability to read Tagore. However, managing school systems requires use of administratively simple criteria that establish acceptable benchmarks at different grades. Without such benchmarks there is always a danger of lowering expectations to the point that children graduate from primary school not able to read and write as adults.

Bangladesh is admittedly faring better than many countries where 50 percent of children cannot read a single word after several years of schooling, partly due to the lack of teaching materials. In planning to improve literacy among Bangladeshi children, the country has a big advantage over those countries, such as India, where multiple languages are spoken.

Capitalising on the fact that we have one primary language, we can easily adopt better teaching techniques for reading. The National Curriculum and Textbook Board has been working hard to introduce supplementary reading materials in primary grades. It is important to note here though, the supplementary reading materials must match children's reading levels.

We lack two important elements essential for improving children's reading skills—adequate teaching time and testing. Let's not confuse testing with our existing public examinations. More time needs to be devoted to the teaching of reading in early primary grades. Children also need more practice in reading, guided by their peers or teachers. In order to measure the results of teaching activities, Early Grade Reading Assessment (EGRA) provides a measure in terms of reading fluency. There are tools to assess reading ability. For instance, ASER in India is a highly popular tool for identifying readers and non-readers. ASER surveys ask primary school students to read a short story at grade two curriculum level.

The literacy benchmark associated with EGRA is reading fluency, measured by the number of words read correctly per minute. EGRA is also a literacy or reading diagnostic tool for teachers to use in their classrooms. If conducted over a nationally representative sample of early primary grade students, EGRA assessments are of immense help in adopting better reading interventions.

World-renowned reading expert Helen Abadzi suggests reading 45-60 words per minute as a threshold for literacy in early primary grades. Some organisations in Bangladesh that work with primary school students follow this prescription, while others use different thresholds. Unfortunately, no agencies have a number, tested by empirical studies, to confidently claim that reading at a particular fluency guarantees that a child will be able to read with comprehension. There is a role for the Government of Bangladesh to determine an appropriate literacy or reading benchmark for a Bangla reader. This benchmark must not be so low as to imply little effort is required to become literate; nor must it be so high as to imply all children must reach high school levels in primary school. Settling on an appropriate fluency benchmark will also help in assessing various reading interventions. Of course, the fluency benchmark for children with disabilities will be different.

Currently, the Ministry of Primary and Mass Education is developing its fourth primary education development programme, for the next five years starting in 2018. It is an ideal moment for the country to determine an appropriate literacy benchmark for early primary grade children and make a commitment that by the end of this primary education programme all graduating primary school students will be able to meet, or preferably exceed, this level.

Shahidul Islam is Senior Education Advisor at USAID Bangladesh. John Richards is a professor at Simon Fraser University, Vancouver, Canada. Authors' views expressed in this column do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) or the United States Government.

Comments