‘Factory owners’ fear of labour unions stems from their loss of control’

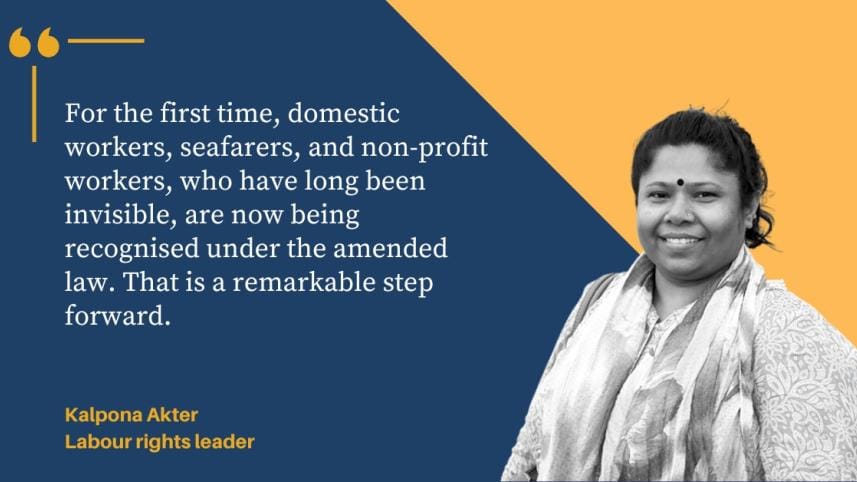

In the wake of the recent amendments to Bangladesh's labour law, Kalpona Akter,president of Bangladesh Garment and Industrial Workers Federation, spoke with Monorom Polok of The Daily Star about factory owners' anxieties over the new unionisation rules, the inclusion of domestic and non-profit workers under legal protection, and other issues.

How do you respond to owners' associations' concern that allowing just 20 workers to form a union could disrupt production and create chaos in factories?

Before I offer my perspective, it is important to first clarify where responsibility lies. The factory owners themselves are entirely responsible for the situation they now call harmful to the industry. For all the things involved, there is no one else to blame—not the workers, not the labour leaders, not the government, not any international organisation.

About seven or eight years ago, a complaint was filed with the International Labour Organization (ILO) governing body under Article 26 against Bangladesh for violating Conventions 87 and 98—those concerning freedom of association and collective bargaining. It clearly showed, with evidence, that workers in Bangladesh were not free to form or join trade unions.

Drawing from my experiences, this is not something entirely new. Around three decades ago, when I used to work in a garment factory, I was expelled and blacklisted simply because I joined and facilitated the formation of a union. The situation has not changed even today, as owners treat it like a crime whenever workers try to form unions or even express interest in learning more about their rights. They harass workers inside and outside the factory premises, often dismiss them, and even physically assault them. Sometimes the workers are also forced to leave their communities.

The owners believed that since they had possessed political connections and power for the last 15 or 16 years, it would always remain the same for them. They regarded themselves as kings and the workers as merely subjects. Subsequently, even after the ILO complaint, they did not seem to consider it seriously.

The interim government has now removed this obstacle for two main reasons: firstly, the working class and trade unions have been fighting for their rights for years now. Secondly, the government could not risk losing credibility in the international arena. The ILO had already been pushing for compliance, and both the European Union and the US trade channels, which have major business ties with Bangladesh, have been putting pressure in this regard. Thus, this change was inevitable and long overdue.

The owners' fear that this change will disrupt work is a misplaced perception. At least a single union was bound to be formed. Earlier, the law allowed up to three unions in a factory. However, for years, the owners' syndicate used their influence and did not allow even one union to form or exist in a functioning way. Now, there might be more than one, depending on the situation. In some factories, unions might form with seven percent of workers; in others, it can be 12 percent or 13 percent, and in some cases, unions can be formed with 20 percent of workers. Depending on the factory size, the magnitude of the unionisation will vary. On the workers' front, this is a major achievement.

Earlier, there was some sort of arrangement with the labour ministry that if one union were registered, no second one would be approved. Garment owners took advantage of this loophole, and also formed what we call "yellow unions," created by the management itself. They now claim that there are 1,400 unions in operation, but in reality, more than half are defunct. There are fewer than 50 factories with any active Collective Bargaining Agreement (CBA).

So, this fear the owners express is less about disruption and more about losing control. Although they verbally acknowledge workers as an equal part of the system, they merely believe in it. If they did, they would have agreed to sit down for negotiations. Furthermore, owners take part in spreading misinformation as well, as seen in the Adamjee Jute Mills case. They claimed that the mill closed down because of labour unions, which is based on no truth. Adamjee was shut down mainly due to political interference and mismanagement, not unionisation.

If both owners and workers are willing to comprehend and respect the amended law, even five unions in one factory will not be an issue, as negotiations would go through a CBA process.

The amended law also brings domestic workers, seafarers, and non-profit employees under legal protection for the first time. What is your assessment of this inclusion?

It is truly historic. Just two days before the amendment, the ILO ratified three major conventions. I was a bit disappointed that Bangladesh had not ratified Convention 189 on domestic workers, but later, the amendment eased my disappointment.

For the first time, domestic workers, seafarers, and non-profit workers—who have long been invisible—are now being recognised under the amended law. That is a remarkable step forward.

But we also need to talk about what this means in practice. For domestic workers, the biggest change will be in how employers treat them. Of course, we are yet to know about the extent of benefits that are to be included in the final gazette. But even with the amendments in place, there is a cultural barrier at play, as domestic workers are often disregarded as "workers" due to social stigma.

For example, in a household, a domestic worker might work from 12pm to 3pm, including lunchtime. But providing lunch to the worker is often at the mercy of the household owner or employer. If a domestic worker requests lunch, it is often considered unacceptable, although it might fall well within the worker's rights.

However, domestic workers often have more negotiation power than, say, garment workers. Employers cannot just dictate terms. Domestic workers often set their own rates and even ask for a raise. That can be seen in a positive light. Nevertheless, domestic workers tend to face more serious issues than other workers, such as domestic abuse, sexual harassment, and gender-based violence. That is why legal protections for them are absolutely crucial. Moreover, most of our recommendations for the amendments were included in the final gazette, and it shows progress, even if small.

Bangladesh has often been praised for passing progressive laws, but implementation remains a challenge. How do you think this new amendment might be implemented?

Implementation is going to be the real test. On paper, it looks good, but without proper enforcement, it will be rendered meaningless.

If we look at our history, no government has ever truly stood on the side of the workers. They have always adhered to the interests of the businesses. The first responsibility of the next government must be to break that pattern. In this case, the interim government has shown some commitment, and the political parties campaigning to assume power have also shown support. But we need to learn from our past and refrain from repeating the same pattern.

Additionally, we need proper infrastructure to make implementation feasible. For example, the Department of Inspection for Factories and Establishments (DIFFE) has repeatedly complained about insufficient manpower and resources. If the state can recruit hundreds of police officials, why not more inspectors to protect workers' rights? Bangladesh has over seven crore workers; therefore, protecting their rights should be a national priority. A large, well-resourced, and sustained institution must be built for this purpose.

The pilot project, the Employment Injury Insurance (EII) scheme, is also an important step in this process. If it can be actualised into a law and implemented properly, it could cover all workers nationwide. Whatever may be the case, we cannot leave things on paper. Implementation must start; there is no alternative to it.

We are living in a changing time, and I'm hopeful. People from all walks of life have become more politically aware, and the actions of the government do not easily go unchecked anymore. Therefore, there lies a strong scope for accountability, and the law must be implemented accordingly.

Finally, what message would you give to both workers and owners as this transition unfolds?

To the workers, I would suggest staying united, knowing their rights, and utilising the fresh avenue the amendments have offered. For the owners, they must accept the change and cooperate. They have long benefited from a system that silenced workers, but that time has come to an end.

If both sides approach with mutual respect, this can be a turning point in Bangladesh's labour history.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments