Anti-Liberation War forces have taken advantage of the failure of democracy

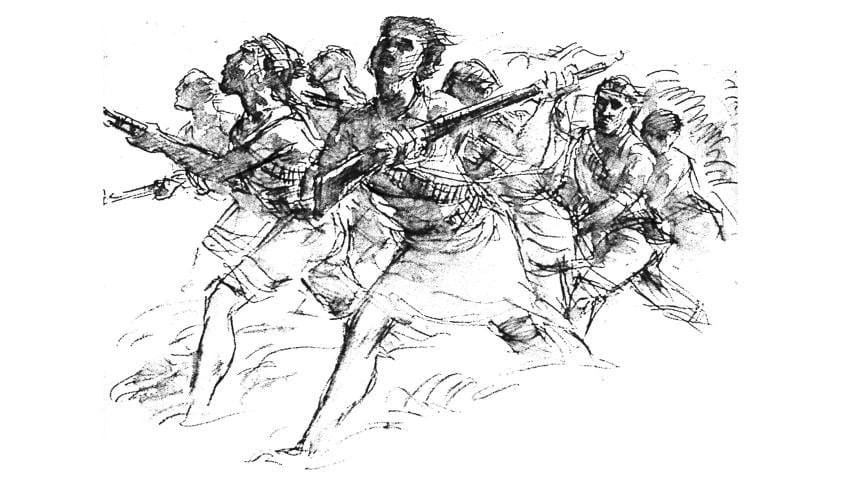

Prothom Alo (PA): The nation reached the Liberation War of 1971 through a long trail of political upheavals and historical turns. You were an active participant in that continuum of struggle. The vision at the time was to build a just, equitable and exploitation-free society in response to West Pakistan's discriminatory and extractive rule. Fifty-four years on, how far do you think today's reality has drifted from that original vision?

Rehman Sobhan (RS): Bangladesh has registered progress and change in many areas since 1971. Pre-1971 disparities in every socio-economic indicator prevailed in favour of West over East Pakistan. Today we are ahead of Pakistan in virtually every development indicator from GDP to human development. Unfortunately, we are far away from constructing an exploitation-free society so that economic inequality and social disparity have widened.

PA: In the two decades following independence, the country witnessed a series of political assassinations, military coups and long stretches of military rule. Yet one of the central aspirations of the Liberation War was to break free from Pakistani militarism and build a democratic society. Although democracy was revived after the 1990 mass uprising, it has stumbled repeatedly, while authoritarian and illiberal tendencies have strengthened. In your view, where does the fundamental flaw lie in our political culture, mind-set and practice?

RS: Sadly, we have over 54 years not been able to build a workable and sustainable democracy. Our struggle with the Pakistani ruling elite was over the denial of democracy which remained the root cause of the economic deprivation of the Bengalis. We have, for a period from 1991 to 2008, had four relatively free and fair elections under a caretaker government in which power has been transferred to an opposition party. But even in this period of 'democratic' rule the institutions of democracy, such as parliament and the judiciary, have not functioned as they were intended to, so that a version of 'illiberal' democracy prevailed. From the introduction of the 15th Amendment doing away with the CTG, we have witnessed the ascendancy of autocratic government which culminated in an absolute monarchy. The source of the problem lies in the appropriation of power in an all-powerful leader, whether as President or elected Prime Minister, and the tribalisation of our democratic politics which has led to a winner-take-all culture.

PA: The failure to fulfil the ideals of 1971, the persistence of inequality, and the democratic backsliding we have seen—did these make the 2024 mass uprising inevitable? Or do you view the events of 2024 through a different explanatory lens?

RS: The uprising of July 2024 was initially inspired by the restoration of quotas for government jobs through a High Court ruling. The persistence of quotas for descendants of freedom fighters half a century after the Liberation War was quite wrong to the point of absurdity. Sheikh Hasina sensibly did away with quotas and later moved to appeal the High Court decision before the Appellate Division. Autocratic, oppressive, unjust and corrupt governance was the ultimate source of the uprising. Sheikh Hasina's unnecessary and inappropriate remarks about razakars fuelled the uprising, bringing the widespread frustrations and anger of the citizens to the surface.

PA: We now see attempts by some to frame the 2024 uprising as being in opposition to the Liberation War itself. Why is this happening? Is this a temporary or isolated effort, or do you think forces opposed to the historical and political aspirations of 1971 have steadily grown stronger and are now, in the post-2024 moment, deliberately trying to undermine the legacy of the Liberation War?

RS: As I have indicated above, the July uprising was inspired by democratic failure and unjust rule. Elements opposed to the Liberation War who have remained embedded in our politics took advantage of the uprising, infiltrated it, and may even have played an important role in its direction. This happens in mass upsurges against autocratic regimes where suppressed forces which have remained well organised and disciplined, even when they were repressed, can readily come into prominence when the opportunity presents itself. In the period of the interim government, they have emerged as a more visible force with strong electoral prospects. They are inclined to use this opportunity to reinterpret their historical collaborationist role with the Pakistan Army in 1971. Being led by politically astute leaders, at this stage of the political process, their position on the Liberation War is likely to be projected with some caution. It, however, remains a part of their political strategy to whitewash their role in 1971.

PA: In an article for Prothom Alo this April, you wrote about Jamaat-e-Islami that, "Although they display restraint in public rhetoric, one of their main objectives is to rewrite history so that, even if they are not seen as heroes of 1971, they at least appear as victims, portraying Bangladesh under Bangabandhu's leadership as having fought the wrong enemy in the wrong war." We are now seeing that this effort is not limited to Jamaat alone; some segments of the student leadership that led the uprising, along with other groups, are also attempting to write history and shape narratives in their own way. There are visible attempts from their side to marginalise or overlook the Liberation War. How do you interpret this trend?

RS: The response of some of the student leadership to the Liberation War has surprised many. Such a position indicates that some elements in the movement were nurtured by anti-liberation forces and have projected such views after 5th August. Others appear to have elevated their strong antipathy to Sheikh Hasina and her party into an antipathy to Bangabandhu and the Liberation War. Both positions have become counterproductive to the political aspirations of the student movement. The role we all looked for from the students and any political party they formed was to delink themselves from the historical and partisan debates which divided the AL and BNP. The students should have projected themselves as a forward-looking force of the 21st century and emerged as a modern-minded third political force which was badly needed to enable Bangladesh to move away from our tribalised politics. Their origins from non-elitist social backgrounds could have provided them with credibility to provide an authentic voice to the concerns of the common people.

PA: During Sheikh Hasina's fifteen and a half years of undemocratic rule, the rhetoric of the Liberation War was frequently used as a political instrument to repress and delegitimise the opposition. Moreover, historical discourse was narrowed to an exclusively Awami League–centric interpretation, restricting broader scholarly and civic engagement with 1971. Do you believe this environment contributed to the emergence of negative perceptions about the Liberation War among the younger generation?

RS: Sheikh Hasina's initial response was motivated by the complete whitewashing of Bangabandhu and the AL from the public domain by the regimes in office between 1975 and 1996. However, when she came to power in 1996, and more so in 2008, she overplayed the image of her father and oversold the prominence and role of the AL in the Liberation War. The objective reality was that the AL was a vanguard force in the struggle for national liberation provided by the democratic mandate received through the 1970 election and the iconic role of Bangabandhu in giving leadership to the struggle for self-rule for the Bangalis. However, other political leaders and parties contributed to this struggle, while our armed forces and the common people of Bangladesh also played a critical role in the Liberation War. Their respective roles should have been more fully recognised both after liberation in 1972 and subsequently by Sheikh Hasina. To assign an exclusive position to the AL in the liberation struggle was both politically and morally wrong and has proved costly for her party as well as to the memory of the Liberation War.

PA: The Awami League's prolonged use of Liberation War rhetoric has, in many ways, deepened social fractures and political divisions. How can these rifts be healed? And specifically, how can we re-engage the younger generation with the Liberation War—its history, its ideals, and the broader practice of historical inquiry?

RS: We need to initiate a process of historical reconciliation through an extended programme of reasoned dialogue both at the political level and among the younger generation. This dialogue should bring all the available historical evidence into the public domain so we can arrive at a more consensual version of history based on facts rather than partisan posturing backed by rhetoric, abuse and even physical threats. The degree of misinformation and its weaponisation for political gain has clouded the understanding of an entire generation about this formative phase in our history.

PA: The 2024 uprising has introduced a host of new questions about Bangladesh's society, politics, and historical trajectory. People had hoped for profound transformation, and the moment did open up such possibilities. Words like "reform," "inclusion," "pluralism," and "a new settlement" echoed everywhere. Fifteen months into the uprising and the interim government, to what extent do you think popular expectations have been met?

RS: Prof. Yunus and the interim government (IG) have rightly recognised that a central message of the July uprising remains that we should not go back to business as usual. The reform initiatives by various Commissions and task forces, summarised in the July Sanad, serve as a positive move to present a set of reforms which would provide Bangladesh with better governance and a more just future. Our long history with the promise of reform provided by every regime from the time of our liberation indicates that the true challenge is to implement whatever reforms or policies a government has presented to the people. In my view, implementation failure more than wrong policies has been the principal source of both democratic dysfunction and malgovernance.

The lack of emphasis by the IG on improving governance through better implementation, whether of law and order or economic management, has been disappointing and a source of frustration to the people. The IG has brought about improvement in some areas, but this has not matched public expectations. In my view, the IG should have given priority to diagnosing implementation failure and should, within their short tenure, have demonstrated how policies and projects already on the statute books can be better implemented.

The future of the reforms under the July Sanad, in reality, can only be implemented by an elected government which stays in office for four to five years, which provides enough time to evaluate the outcome of a reform. It is a political and juridical mistake to believe that an elected government can be bound by a Sanad mandated through a referendum. The future of such reforms will depend on the political commitment of the elected government, the strength of the elected opposition to pressure them in parliament to carry out and implement reforms, and the activism of civil society to serve as watchdogs over the passage and implementation not just of reforms but the election manifesto of the elected government.

The two issues which were very much in the minds of the July uprising, pluralism and inclusion, have unfortunately not received the attention they demand. The IG government has demonstrated its own limitations in protecting women, minorities and political elements which are currently out of favour. None of the commissions, including the economic task forces, have provided any clear agenda for an inclusive development strategy, nor has the IG, through the Sanad, satisfactorily addressed the issue of pluralism. The neglect of the recommendations of the Women's Commission remains a case in point.

PA: The interim government's inaction and inability to curb mob violence have emboldened the far right. Women, ethnic and religious minorities, Bauls, and followers of mazar traditions have faced attacks, and their spaces have shrunk. Major political parties have also failed to play an assertive role in protecting their rights. Liberal groups remain cornered and silent. What impact do you think this will have on our society going forward?

RS: The failure of the IG to discourage and take firm action against mob violence remains conspicuous. Their failure is both a declaration of intent as well as a reflection of their weak governance capacity. Political parties have made rhetorical observations but have done little to act against such violence. Verbal abuse and instigation of violence emanating from social media remain unattended. The IG should have set standards on how to deal with such a process. It is not clear if elected political parties will be any more willing to take action to contain such forces since some of this violence emanates from political elements who now hope to get elected to the 13th Sanghsad. The failure of the IG to deal with violence has now opened up a new and more dangerous phase on the eve of elections through the resort to gun violence against particular political contestants.

PA: For more than three decades, Bangladeshi politics has revolved around a rigid two-party structure. You have argued that this bipolar divide has produced a kind of tribalism in national politics. How realistic is the emergence of a third political force in Bangladesh?

RS: As I pointed out earlier, we had entertained much hope that the students may emerge as a third force. Their statements, actions and efforts at forming a political party do not provide much encouragement that they will emerge as such a force. The Jamaat-e-Islami has clearly emerged as a strong political force. During and after the elections they will serve as the bipolar force in contestation with the BNP in politics and parliament, given the absence of the Awami League.

The big question which no one is willing to publicly discuss is the future role of the Awami League which provided one of the two pillars of our bipolar politics. They remain a party with a 77-year history and a sizeable electoral following. Whatever their wrongdoing, this force will not wither away in our tribalised polity. This is an issue which will have to be addressed by the elected government. Failure to do so will open up an uncertain future for the workings of our 'reformed' political order.

PA: In your writings and lectures, you have repeatedly emphasised the idea of an "unfinished Liberation War." In your view, in what sense does our Liberation War remain incomplete? And how do we, as a nation, carry forward the unfinished journeys of that struggle?

RS: The Liberation War promised democracy, secularism, socialism and nationalism. The first three principles have never been fully realised. Nor does the near future provide much prospect for their realisation. These three foundational principles of our nationhood have indeed been excluded from the July Sanad. The idea of nationalism remains contested even after 54 years. I fear that my own political journey, at the age of 90, may remain unfinished.

The interview was originally published in Bangla by Prothom Alo on December 16, 2025. It was conducted by AKM Zakaria and Manoj Dey.

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments