Vulnerable workers deserve special protection

The tragic fire at the Arian Fashion factory in Dhaka's Rupnagar stands as a reminder of the regulatory failures that continue to plague the margins of Bangladesh's industrial sector. The deaths of at least seven workers—aged between 13 and 18, many of them recent school dropouts earning poverty wages—reveal how profoundly we have failed to protect the most vulnerable workers.

Under the Bangladesh Labour Act of 2006, employing anyone under the age of 14 is strictly prohibited, while adolescents, aged 14 to 18, may only engage in non-hazardous work for a maximum of five hours per day. Yet, the victims were working full shifts, often with overtime, in a building where hazardous chemicals fuelled the fatal blaze. To compound this, they were paid sub-minimum wages—around Tk 7,500 a month—a clear indication that the factory operated outside the legal framework, preying on the desperation of impoverished families to secure exploitable labour.

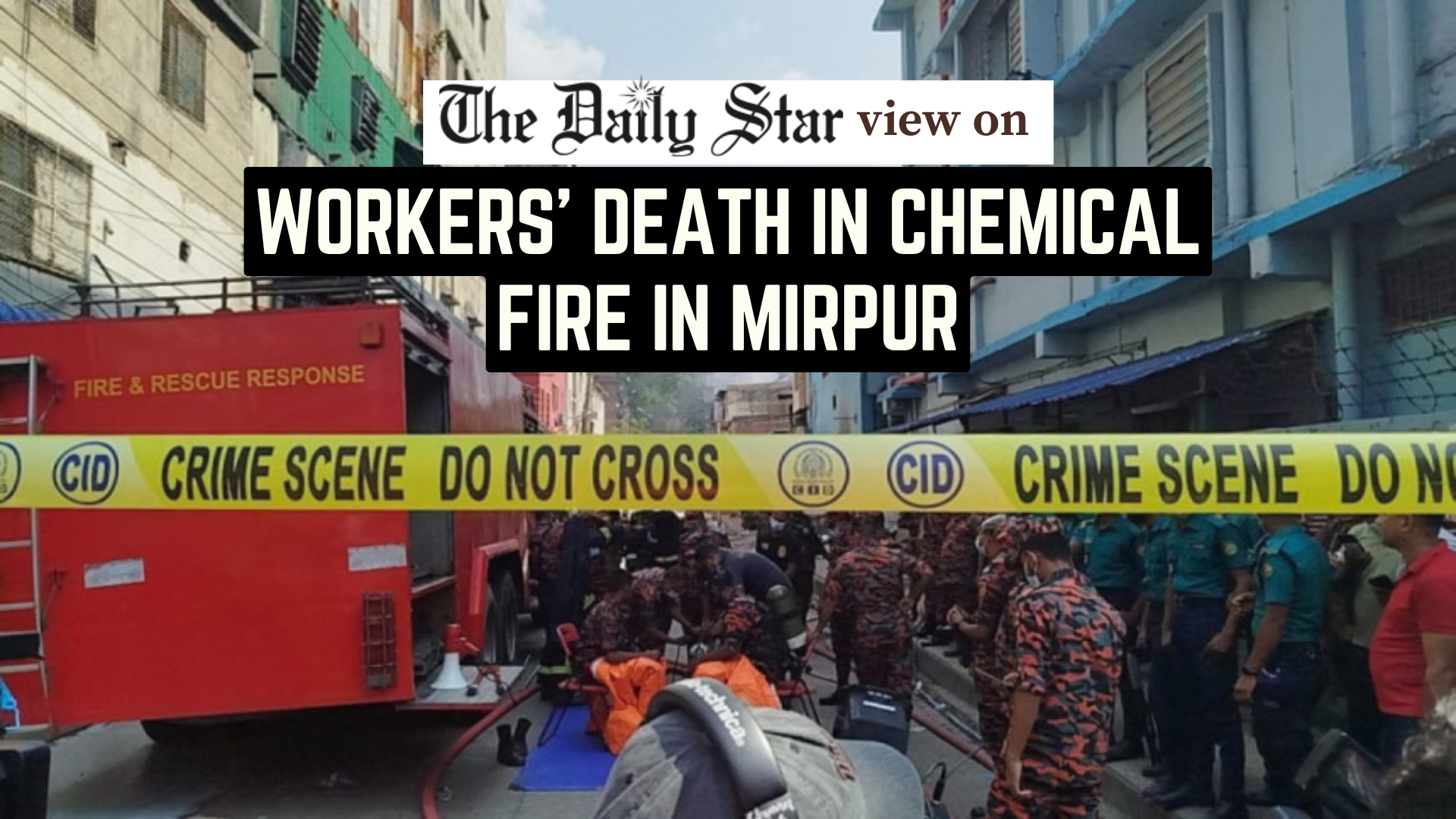

Since the Rana Plaza disaster in 2013, the nation has earned global recognition for improving safety standards within factories affiliated with the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association. However, Arian Fashion was not a member of this association. The fire—and its horrific aftermath, including locked exits and volatile chemicals—occurred within the vast, unregulated sector that lies beyond formal oversight. The immediate failure rests with regulators that routinely ignore such non-compliant operations, many of which function as murky subcontractors or serve domestic markets.

The lethality of the Rupnagar fire—with toxic gas responsible for instant fatalities—reveals a parallel failure at the highest levels of governance. For more than a decade, successive administrations have pledged to relocate hazardous chemical warehouses and factories from densely populated areas, following the devastating Nimtoli (2010) and Churihatta (2019) fires. Industrial units handling hazardous materials are explicitly banned in residential zones under the 1997 Environment Conservation Rules. But relocation to designated industrial zones like Munshiganj remain stalled for years amid bureaucratic inertia and commercial resistance.

This failure of prevention contributes to a massive, yet often ignored, public health crisis: government reports indicate that roughly 1,500 people die from burn injuries every year and a staggering 12.9 lakh suffer injuries annually. This vast number highlights the critical scarcity of burn treatment facilities and trained personnel outside the capital. The tragic confluence of underpaid, often child, labour and explosive chemicals in a residential area is the inevitable, lethal outcome of an institutional indifference.

A swift and impartial investigation is now imperative, alongside criminal accountability for the owners and negligent officials, but lasting change demands a systemic response. The successes achieved in monitored factories must not obscure the dangers festering in the unmonitored periphery. The government must expand the regulatory net through a robust, well-funded inspection system capable of identifying and shutting down non-compliant factories. Equally vital is the establishment of comprehensive supply chain transparency, ensuring that no tier of the industry can profit from illegal, underpaid labour.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments