For whom the bell tolls

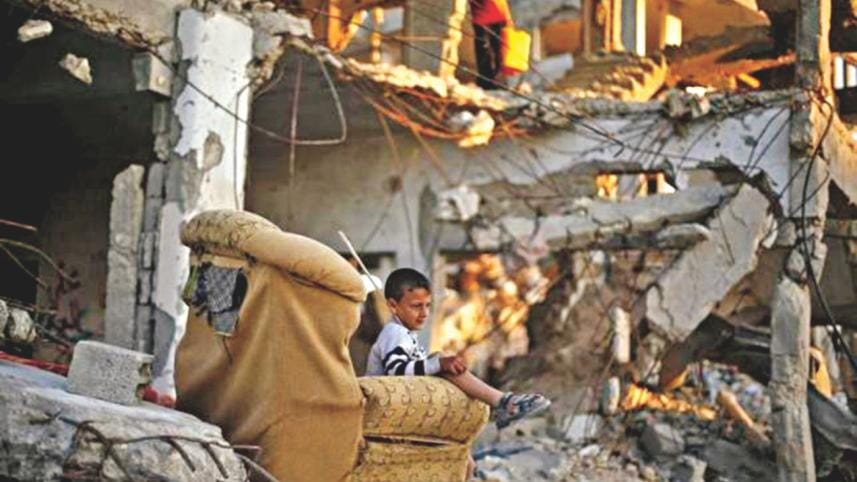

How many people died in 2015? Did anyone keep count? Even if they did, what are we to do with this information? Is it possible to feel the death of a stranger? Can we grieve in an unframed abstract?

"Any man's death diminishes me", the grand idea put forward by John Donne has always seemed exaggerated to me. Donne, the English poet and cleric, expressed this thought about four hundred years ago when someone's death was signalled by a single church bell. There was no "sad face" to reverberate down the fibre-optic lines, carried by invisible storms of ones and zeros that fill the air today from cell tower to cell tower and magically end up in the palms of our hands.

"It tolls for thee," Donne wrote in his timeless poem No Man Is an Island. But does it really? What does it actually mean to believe in the notion that any man's death diminishes me? In what sense diminishes? Logic would suggest otherwise: the more die off, the more resources there will be for those who remain. Were Donne's words just a "right" thing to say - a slice of moral claptrap dished out to us so we could feel good about ourselves, and by extension, humanity?

And even if we emphatically accepted this magnificent idea, what to make of an act of empathy so complete that encompasses even those we have never met or know nothing about? Is it then a pleasure to pretend to feel for strangers? Is it to be reassured that we are not suffering; we are not dead?

Last week Halima Khatun, 60, of Nilphamari died of severe burns while trying to keep warm by sitting next to a clay oven. And this week in Jhenidah, a 40 year-old man burnt his three nephews to death. Feel their deaths, do we? Do we treat them as the immediate urgencies that they are or do they become an extension of our ego, keys to which the media flaunt and jingle before our nose 24/7?

Whenever an accident or a disaster takes place, numbers are always tossed up by newspapers and TV channels; there seems a false need to know exactly how many died and how many were injured. Live coverage supersedes live coverage. Correspondents speaking in various languages and dialects look straight into the camera describing the indescribable. And when the death toll is finally confirmed, it is as if we were mourning a quantity rather than people, since the counting exercise has become a way of establishing objective significance in the world. Still some of us become misty eyed for a minute or two and even try to help if we can.

But Donne seemed to be inviting a response that is deeper and more consistent: Any death makes me smaller because the world is a map of interconnections. Since the entire world suffers a numerical loss at an individual's death, one must feel connected to the entire world to feel the subtraction equally.

For most of us that's where the difficulty lies - in feeling a part of the world in the first place, not in doling out money or showing a moment's sympathy to a distant tragedy. Donne's thesis was that empathy ought not to be what we put on display from time to time but what we demonstrate all the time - for the sufferers who among us, for the family down the street whose plight goes untelevised - for all those in fact whom we might actually help. Thus we could be prepared for history's lowest points so that when the human race goes berserk and comes up with a Hitler, a Pol Pot or a George W Bush, we would not turn our backs on those in danger.

In his book Language and Silence, George Steiner was baffled to consider how unspeakable atrocities could be occurring in occupied Poland during World War II at precisely the same time that people in New York were making love or going to the movies. Were there two kinds of time in the world, the French-born US philosopher and writer, wondered - "good times" and "inhuman time"? The thought is extremely disturbing and perplexing. What was I doing when Halima was burning?

It is, therefore, necessary to make a connection with all those who die, under any circumstance, in order to keep one's capacity for empathy vigilant. I doubt there are two kinds of time in the world, but there seem to be two kinds of empathy; one that weeps and evanesces, and one that never leaves the watch. Empathy, like all virtues, must have some application to the future. If we do not deeply feel the deaths we are apparently powerless to prevent, how would we be alert to the deaths we might put an end to?

Of course, this is asking a lot of you and me, who are after all, pretty good people, who recognise despair when we see it and do the best we can when appeals are made.

The show must go on.

The writer is a member of the editorial team at The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments