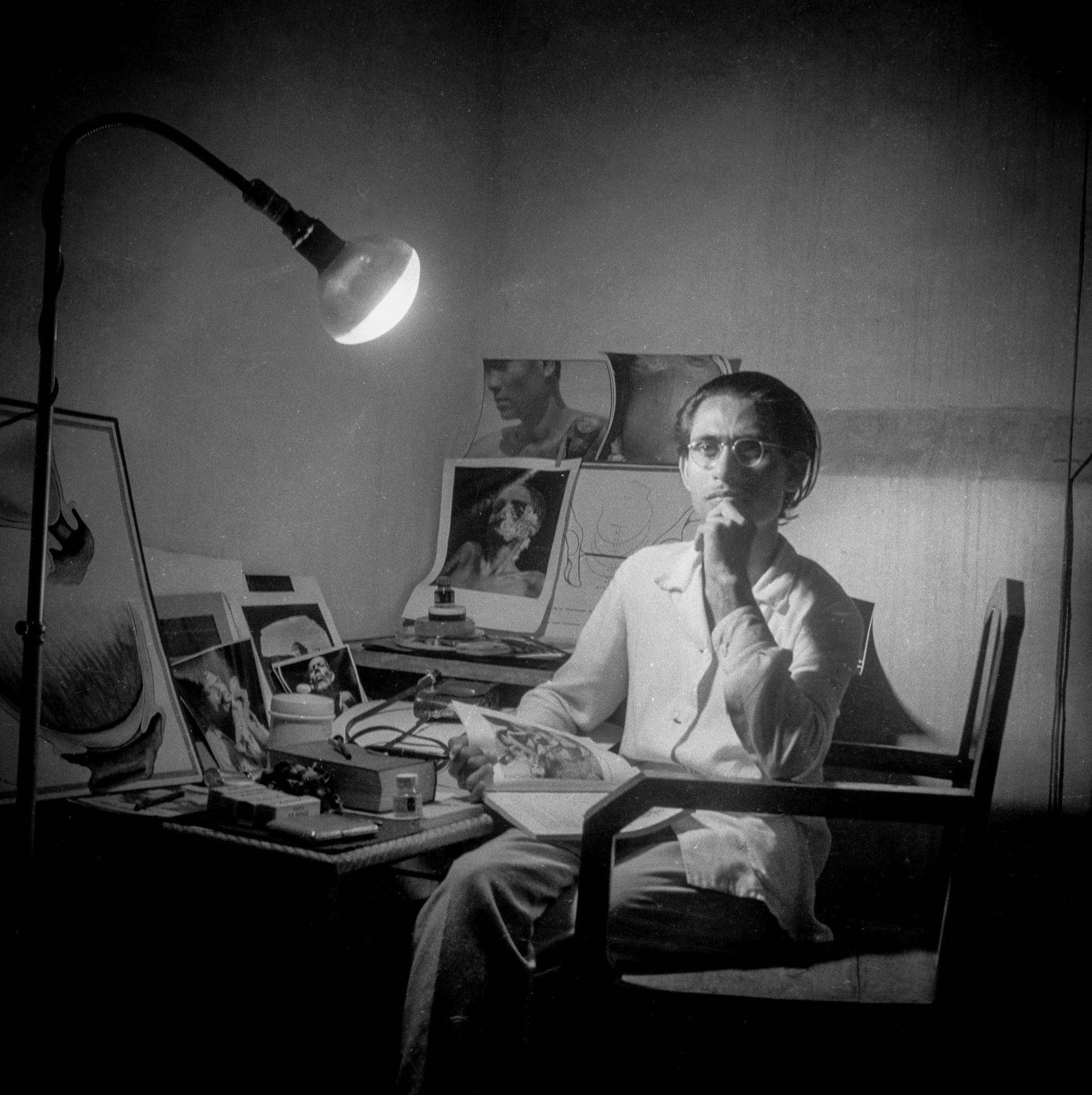

Amanul Huq: The romantic documentarian

The international photography festival Chobi Mela will begin on January 16. This year’s festival is being organised around the theme “Punô”—meaning again or to begin anew, differently. The contemporary world is looking towards a new time, and it is this idea that has shaped the festival. A special highlight of the event is the exhibition titled “Amanul Huq: The Romantic Documentarian.” The exhibition will feature Amanul Huq’s photographs of the Language Movement of 1952, the mass uprising of 1969, the election campaigns of 1970, the Liberation War of 1971, as well as images of Bangladesh’s rivers, women, rural life, and various moments with Satyajit Ray. The exhibition will run at the Bangladesh National Museum until January 31.

Amanul Huq was born on the banks of the Jamuna, in his maternal grandparents’ home in Kadda village of Sirajganj, exactly one hundred years ago, on an autumn evening in Kartik. After his birth, his father noted in his diary: “6 November 1925, 26 Kartik, 1332 Bangla year.” Born on a Saturday, the newborn was named Amanul Huq, with the nickname Moti. Throughout his life, Amanul Huq travelled across the plains of Bengal, journeying by barge along rivers and canals, capturing through his camera reflections of a vast and abundant life. Rivers, women, boats, water and land, the sky, and the lives of people along the riverbanks became his meditation. Through his hands, the foundations of creative photographic practice in Bangladesh were laid.

On a Sunday morning in 1959, Amanul, accompanied by poet Subhash Mukhopadhyay, visited Satyajit Ray’s home at 3 Lake Temple Road. That day, Amanul presented Ray with his framed photograph “Idle Noon.” The image deeply impressed Satyajit, who praised it without reservation and compared it to the work of the world-renowned French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson. This photograph secured Amanul a special place in Satyajit Ray’s heart.

Amanul’s ancestral home was in Ghorjan village of Sirajganj. Because of his father’s job, his childhood was spent in Shahjadpur and Ullapara. During the British period, Shahjadpur was a subdivision; today it is an upazila of Sirajganj. In the 1940s, his father, Dr Abdul Huq, bought a house in Monirampur, the heart of Shahjadpur town, and settled there permanently. His mother, Hajera Khatun, was trained in midwifery. Amanul was the second of eleven siblings, though two sisters died prematurely. In 1932, he began his primary education at Shahjadpur Minor English School (now Ibrahim Girls’ High School). As he grew up, he developed an interest in drawing, receiving his first lessons from his father. In 1939, he was admitted to Ullapara Merchant High School in Class Six. By the time he reached Class Eight, he was already obsessed with images. At the time, communal harmony between Hindus and Muslims in Shahjadpur was strong. There were two studio photographers in the area—Biren Saha and Atul Saha. It was after seeing Biren Saha that Amanul became fascinated with the camera. The year was 1941.

In those days, almost every Hindu and Muslim household kept a panjika (almanac). One day, Amanul saw an advertisement for a Japanese camera in the almanac and wrote by post, saying, “I want this camera.” A few days later, a beautiful parcel arrived at his home from Kolkata. On opening it, he realised it was not a real camera but a toy. The young Amanul was heartbroken and burst into tears. Soon afterwards, he got hold of a Baby Brownie camera and began taking photographs with it. Every morning, he would wake up and travel far from home—to remote villages such as Borpangashi in Ullapara, Kadda in Sirajganj, and Ruppur, Potajia, and Rautara in Shahjadpur. He often went without food all day, which eventually led to ulcers. The physical toll of his undisciplined childhood habits stayed with him throughout his life.

After passing his matriculation, he enrolled at Pabna Edward College, but his obsession with photography meant he could no longer concentrate on his studies. Around this time, he also became deeply interested in playing the violin. The country was then experiencing the Second World War and the post-famine devastation of the 1940s. During this period, Amanul left Sirajganj and came to Dhaka. The suffering and deprivation of the urban poor on Dhaka’s streets became the central subject of his photographic work. Through these humane images, he came to know the great artist Zainul Abedin, who recognised in him a rare artistic talent. Inspired by Zainul Abedin, Amanul enrolled at the Dhaka Art College, but even there he could not settle.

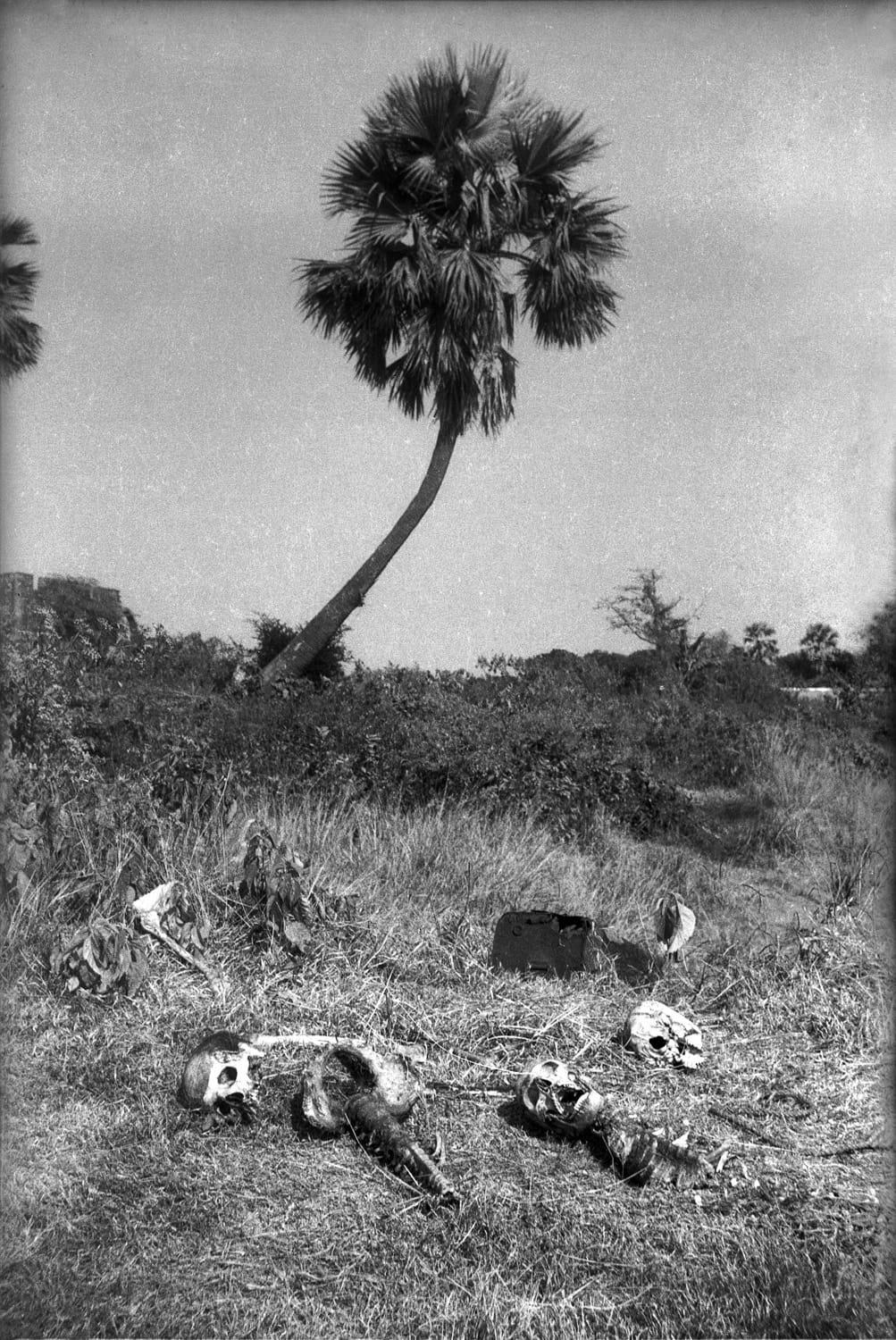

In the post-Partition period, he became acquainted with Habibullah Bahar Chowdhury, then the provincial Minister for Health. With his support, Amanul secured a position as an artist—as photographers were then called—at Dhaka Medical College Hospital. Alongside photography, he drew illustrations of various parts of the human body for medical students. A few years later, the Language Movement began. On the blood-stained afternoon of February 21, risking his life, Amanul photographed the shattered skull of language martyr Rafiquddin Ahmed, who was killed while demanding recognition for Bangla, using his Zeiss Ikon camera. Renowned journalist Kazi Mohammad Idris sent Amanul’s photograph to the office of The Daily Azad that very day, and blocks were even prepared for printing. But late at night, just as printing was about to begin, complications arose. Due to objections from the owners, the photograph was never published. Another block had been sent to students of Dhaka University, and the image appeared in their leaflets, which were later confiscated by the police.

This photograph taken by Amanul remains a significant document of the Language Movement. It placed the then West Pakistani government under severe pressure, as it proved conclusively that the police had not fired blank shots to disperse the procession, but had instead opened fire with lethal intent. Naturally, Amanul fell out of favour with the authorities. Intelligence agencies began searching for him relentlessly. To avoid arrest, he went into hiding and was forced to resign from his job at Dhaka Medical College. During this time, he also lost his beloved camera, cutting off his source of income. As his situation grew increasingly desperate while in hiding, he was compelled to sell his cherished violin. With the small sum he received from its sale, he set off for Kolkata.

The year 1952 was a crucial moment in Amanul Haque’s life. That year, his first joint photography exhibition was held at the Farmers’ Fair of Tejgaon Agricultural College, alongside photographers Noazesh Ahmed and Naib Uddin Ahmed. A review of the exhibition was published in Cultural Geography. His photographs were also shown at England’s Festival of Britain exhibition. That same year, the autumn special issue of Kolkata’s progressive monthly magazine Nabya Sahitya featured his photograph titled “Idle Noon” on its cover. After its publication, art lovers on both sides of Bengal were visibly stirred, whispering among themselves: Who is this extraordinary photographer?

During his time in Kolkata, Amanul became acquainted with Satyajit Ray, who had by then achieved global fame with Pather Panchali and was in the process of writing Devi. On a Sunday morning in 1959, Amanul, accompanied by poet Subhash Mukhopadhyay, visited Satyajit Ray’s home at 3 Lake Temple Road. That day, Amanul presented Ray with his framed photograph “Idle Noon.” The image deeply impressed Satyajit, who praised it without reservation and compared it to the work of the world-renowned French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson. This photograph secured Amanul a special place in Satyajit Ray’s heart. Thereafter, Amanul became Ray’s close companion during the shoots of Devi, Teen Kanya, Kanchenjungha, Mahanagar, The Postmaster, Nayak, Ghare-Baire, as well as Ray’s documentary on Rabindranath Tagore. Amanul addressed Satyajit as his guru, while Satyajit regarded him as a friend. These details are recorded in the biography of Satyajit Ray by Marie Seton.

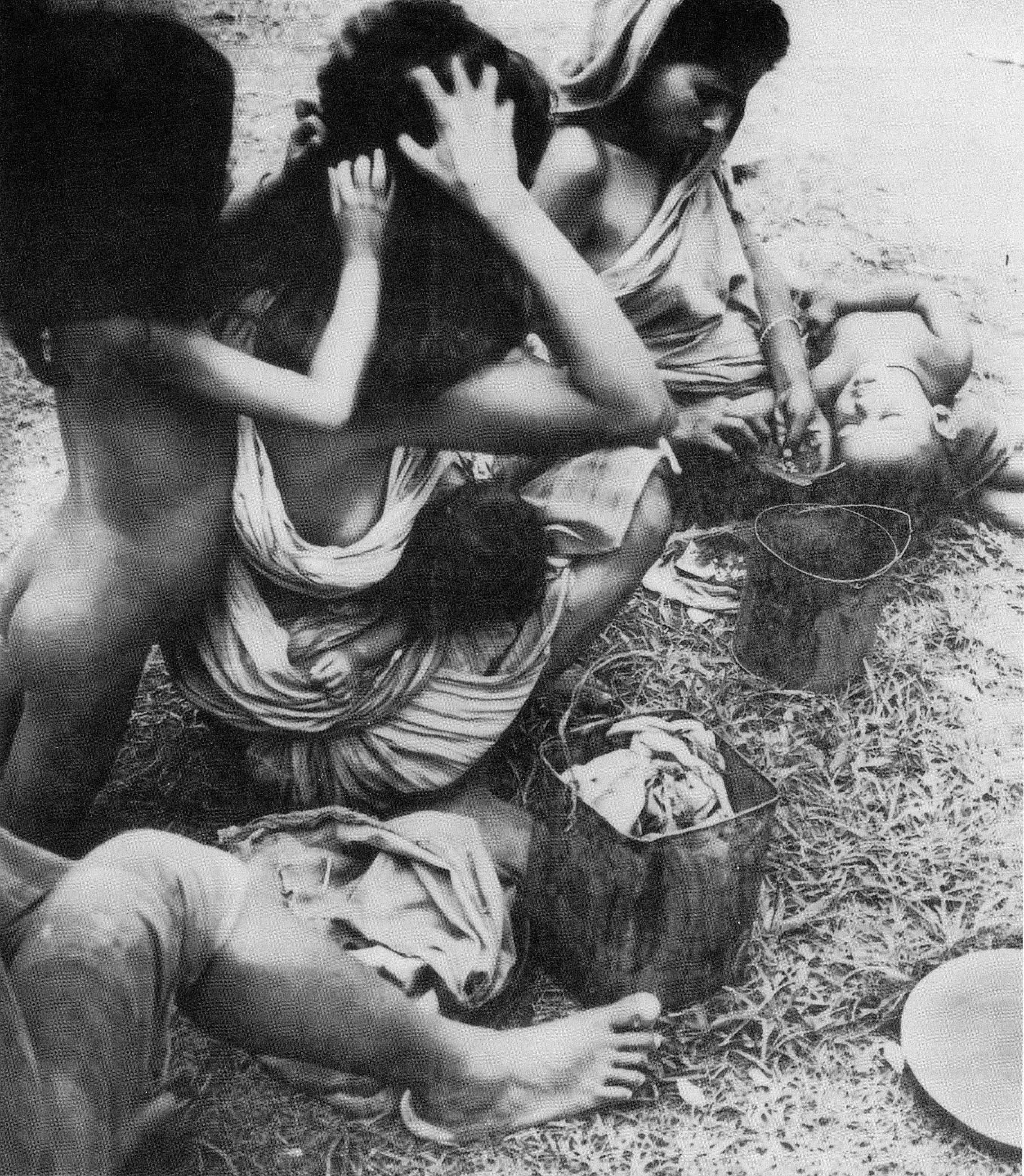

Following the Indo-Pak war of 1965, Amanul returned home from Kolkata. In Dhaka, he stayed at his maternal uncle Shamsuddin Almaji’s house in Azimpur. The country was then simmering with the agitation surrounding the Six-Point Movement, which would soon lead to the mass uprising of 1969. The election of 1970, the Liberation War of 1971, and the post-war period all became subjects of his committed and militant camera.

Rabindranath Tagore and his life aboard the bajra had a profound influence on Amanul. During his childhood, owing to his father’s job, he lived in the staff quarters of Shahjadpur Government Hospital. To the west of the hospital stood Tagore’s kuthibari. Between the hospital and the kuthibari flowed a thin stream of the Karatoya River, which dried up during the dry season. It was this kuthibari that shaped Amanul’s artistic life.

After returning to the country, drawn by his roots, Amanul would often travel to Shahjadpur—where his childhood had first taken flight. Walking through the villages of Rautara, Potajia, and Ruppur, he photographed the people, crop fields, boat races, and village games. In 1976, he met Anath Ali Majhi, a boatman from Rautara village. From then on, for more than two decades, Amanul drifted aboard Anath Majhi’s three-cabin bajra, photographing life along the Jamuna, Padma, Baral, Phuljhuri, Hurasagar, Karatoya, Ichamati, Kaliganga rivers, as well as the Gazna beel. The people who lived by these rivers became the subjects of his photographs, and to them he became “Motin Bhai.” Whenever his bajra passed by a village, children would shout with joy, ÒdUK ‡Zvjv jvI hvq Ó (the photography boat is passing by).

Whenever he visited Shahjadpur, Amanul would first stay at the Rautara zamindar house, where his cousin Eliza Khan Eli lived. At times, he stayed at the Ruppur home of his cousin Abdul Momen Almaji Monu, or at his own house, Rani Kutir. For over a decade and a half, Amanul photographed Eli as his model, many of which were published as cover images of special issues of the weekly Bichitra. In Dhaka, he also worked with a model named Nasrin Jahan Khan Ulka. In addition, he photographed several unknown village women as models. He personally selected every detail—their clothing, jewellery, and styling. Through his romantic lens, Amanul sought to portray an eternal image of Bengali womanhood.

Amanul was never a seeker of fame; such things did not preoccupy him. Yet recognition came to him like a tide. In 1954, a literary conference was held in Dhaka, attended by poets, writers, and journalists from around the world. At this conference, a special exhibition titled “Amar Desh”, featuring over a hundred of Amanul’s photographs, was organised—his first solo photography exhibition. It received a strong response from the intellectual community. His second solo exhibition took place in 1957 as part of the Kagmari Conference in Tangail, organised by Maulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani, who addressed Amanul simply as “Shilpi”—the artist. That same year, when China’s first Prime Minister Zhou Enlai visited East Pakistan, United Front leader Ataur Rahman presented Amanul Huq’s Amar Desh album to him as a gift.

During the 1950s and 1960s, photographs from Amanul’s Amar Desh series were published in Observer Sunday Magazine, Daily Pakistan (monthly edition), Dilruba, Mahe-Nao, and Saugat. His photographs also appeared in Ittefaq and The Daily Sangbad. After independence, his images regularly adorned the covers of Weekly Bichitra and the fortnightly Betar Bangla. As the special photographer of Daily Purbodesh, his photographs were frequently used on the covers of the paper’s magazine supplements marking national occasions. In the later years of his life, his work was prominently featured in special issues of Daily Janakantha. He also wrote memoir-essays for Weekly Bichitra and Weekly Chitrali. He is the author of four enduring works—Ekusher Tamasuk, Prasanga Satyajit, Cameray Swadesh-er Mukh, and Smritichitra—all published by Sahitya Prakash.

For his outstanding contribution to the Language Movement, Amanul Haque was awarded the Ekushey Padak in 2011. He was a man of rare integrity and self-denial. Throughout his life, he lived in financial hardship and never enjoyed material comfort. At the time of receiving the Ekushey Padak, he was given a cash award of five lakh taka and a house in Mohammadpur. He returned the house and said with quiet humility, “Even today, many freedom fighters sleep on the streets. I have a place to sleep. I do not need this house.” With dignity and modesty, he gave the house back. He also donated the gold medal and citation he received as part of the Ekushey Padak to the Liberation War Museum.

In addition to the Ekushey Padak, Amanul received numerous honours: the Lifetime Achievement Award at the Sixth International Chobi Mela in 2011; The Daily Star Celebrating Life Lifetime Achievement Award in 2012; the Janakantha Protibha Award in 1999; and in 2000, an honour as a language activist from the Bangladesh National Museum on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Language Movement. In 2009, he was awarded an honorary fellowship of the Bangla Academy. That same year, the Dhaka 400 Years Celebration Citizens’ Committee honoured him as a language activist. In 1989, he was granted lifetime membership of the Bangladesh Photographic Society.

Amanul never married and spent his life moving between the homes of his siblings. In his later years, he lived at his elder brother’s flat in the Aziz Co-operative Society in Shahbagh. During that time, he wrote in his diary: “Please do not arrange any formalities after my death. This is my request and my final wish. I wish to take refuge in the lap of nature.” Amanul Huq passed away on April 3, 2013 at the age of 88.He was laid to rest at the Martyred Intellectuals’ Cemetery in Mirpur. At his feet stands a krishnachura tree, and by his head a glowing lamppost—as if marking the sun and light he had always sought.

Throughout his life, Amanul Huq pursued creative photography with unwavering devotion. Through the lens of his camera, he observed society and the people of the country with deep attentiveness, creating the photographic series “Amar Desh.” His images continue to speak on his behalf, long after his passing.

Shahadat Parvez is a photographer and researcher. The article is translated by Samia Huda.

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.