Repeated rail freight failures are no longer acceptable

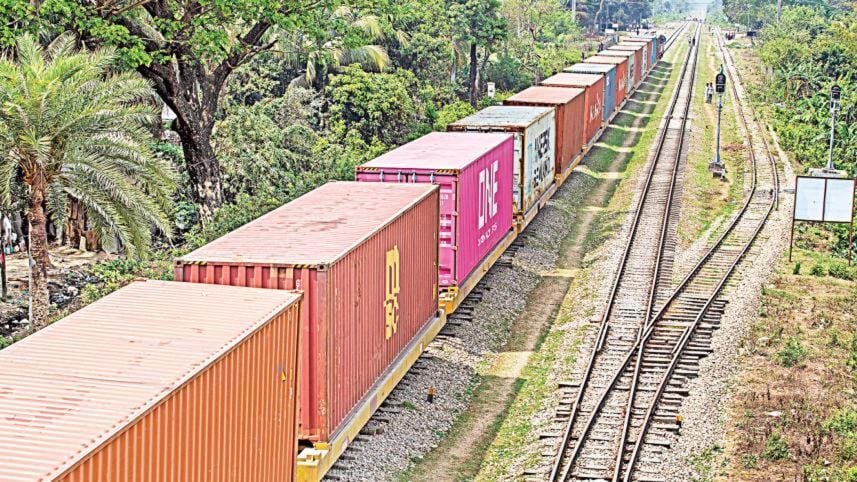

Every few years, Bangladesh Railway’s (BR) container services collapse under the same explanation: a shortage of locomotives. Each time, the consequences extend far beyond the railyard, reaching factories, ports, shipping lines, and buyer offices overseas. The most recent disruption between Chattogram Port and Dhaka’s Kamalapur Inland Container Depot (ICD), widely reported in the press, is not an isolated operational failure. It is the predictable outcome of a system that still does not fully appreciate what international cargo logistics require: predictability over promises.

I spent more than a decade working at ICD Kamalapur, for much of that period heading the facility on behalf of the Chittagong Port Authority. During those years, locomotive crises occurred repeatedly. Each episode disrupted container movements between Chattogram and Dhaka, undermined service schedules, and gradually eroded customer confidence. The pattern has never fundamentally changed—only the scale of the damage.

Railway officials often argue that they have little choice but to prioritise passenger trains due to political and social sensitivities. While that reality cannot be ignored, it also exposes a core contradiction. Container freight generates significantly higher revenue than passenger services, yet freight operations are consistently the first to be sacrificed whenever resources are constrained. Short-term optics continue to override long-term economic logic, even though the costs of that decision are borne by exporters and, ultimately, by the national economy.

For international cargo, particularly exports, reliability is non-negotiable. Global supply chains operate on fixed shipping windows, vessel cut-off times, and contractual delivery obligations. If transport services are not predictable, exporters will not use them—regardless of price or stated capacity. This is precisely what happened at ICD Kamalapur.

Once the ICD failed to provide scheduled and dependable rail services, exporters—especially from the ready-made garments sector—began to withdraw. Volumes declined sharply. Regaining those users proved far more difficult than attracting new ones would have been. In logistics, trust is cumulative but fragile; once broken, it does not return easily.

Today, the RMG sector barely uses ICD Kamalapur for exports and does not use it at all for imports. The ICD’s remaining users are primarily commercial importers, whose decisions are influenced less by transit reliability and more by customs administration behaviour. When customs enforcement is strict, import volumes shrink; when it is more accommodating, volumes flow despite delays and inefficiencies. These users tend to be price-insensitive and, as a result, they rarely raise formal complaints. Their tolerance has masked deeper structural failures.

Exporters operate under entirely different constraints. RMG shipments are time-sensitive, buyer-driven, and penalty-exposed. A missed sailing can result in airfreight costs, order cancellations, or loss of buyer confidence. For such exporters, an ICD that cannot guarantee train schedules is not a support mechanism but a risk.

This is particularly unfortunate because ICD Kamalapur possesses a critical structural advantage for exports. Once containers are stuffed and sealed at the ICD, they move directly into Chattogram port terminals without intermediate handling. The risk of pilferage in transit is virtually nonexistent, barring extraordinary situations within restricted port areas. This should have made the ICD a preferred gateway for garment exports. Security, however, cannot compensate for uncertainty.

The limited number of exporters who continue to use ICD-based exports—often under special arrangements or buyer-specific requirements—only highlights how narrow the ICD’s relevance has become. This is not the result of insufficient demand but of institutional misalignment. Too many decision-makers still view rail freight as a secondary function rather than a strategic enabler of trade. The consequences of this mindset are now evident.

Against this backdrop, Bangladesh Railway’s plans for new inland container depots deserve scrutiny. The proposed ICD at Dhirasram in Gazipur reflects a recognition that Kamalapur is no longer viable in its current location. Although I have previously advocated for Pubail as a more logical alternative to Dhirasram, given its existing rail connectivity, lower development cost, and faster implementation potential, focusing exclusively on site selection risks missing the more fundamental issue.

BR has also moved forward with plans for another ICD at Ghorashal under a public-private partnership involving Shasha Denim and Incontrade, reportedly under a design, build, finance, operate, maintain and transfer (DBFOT) model. These developments suggest that new financing and operating structures are being considered. Yet, whether an ICD is built at Dhirasram, Pubail, or Ghorashal, its success will not be determined primarily by location or contractual form. It will depend on whether it is operated as a genuine logistics enterprise, with enforceable service standards, professional management, and insulation from ad hoc operational decisions.

If new ICDs are run under the same institutional assumptions that have constrained Kamalapur—where passenger trains routinely get priority over freight services—then larger yards and modern equipment will deliver little improvement. Infrastructure alone does not create reliability. Governance does.

Any future ICD intended to serve the RMG sector must offer scheduled block trains, guaranteed cut-off times, transparent disruption management, and full integration with customs and port systems. It must be accountable to its users. Only under such conditions will exporters consider rail a dependable component of their supply chains.

Equally important is location. Kamalapur’s constraints are no longer limited to rail capacity; they are geographic and structural. Situated in the heart of Dhaka, it is encircled by severe road congestion, restricted truck movement, and zero scope for expansion. Any new ICD must be outside the city core, connected to bypass roads, and designed to support uninterrupted cargo flows.

If these principles are applied, a professionally operated ICD—whether public, private, or PPP—could finally align rail transport with the needs of exporters, creating the path for the RMG sector to return to rail and rely on it.

This, however, requires BR to confront its central contradiction. Freight cannot continue to be treated as expendable. As long as locomotives assigned to container services can be withdrawn at short notice to cover passenger shortfalls, no ICD will earn the trust of time-sensitive exporters. That is not simply a logistical misfortune; it is a policy failure.

Repeating that failure at new locations would be far more costly. The question facing policymakers is no longer whether Bangladesh needs more ICDs. It is whether Bangladesh is prepared to operate them as international trade infrastructure, rather than as peripheral extensions of a passenger-focused railway.

Exports run on predictability. Our railways must learn to do the same.

Ahamedul Karim Chowdhury is adjunct faculty at Bangladesh Maritime University and former head of the Kamalapur Inland Container Depot (ICD) and the Pangaon Inland Container Terminal under Chittagong Port Authority.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries, and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments