The Gini is out of the bottle

For Didar Hossain, a shopkeeper in Chattogram, the celebrated expansion of Bangladesh’s economy is a distant rumour.

With a fifth-grade education and a monthly income of roughly Tk 10,000, Didar supports a family of four and ageing parents whose medical bills consume a quarter of his earnings.

He owns a patch of land in his village, yet it lies fallow; farming it would cost more than the crops are worth. To make ends meet, he borrows from relatives and cuts back on food.

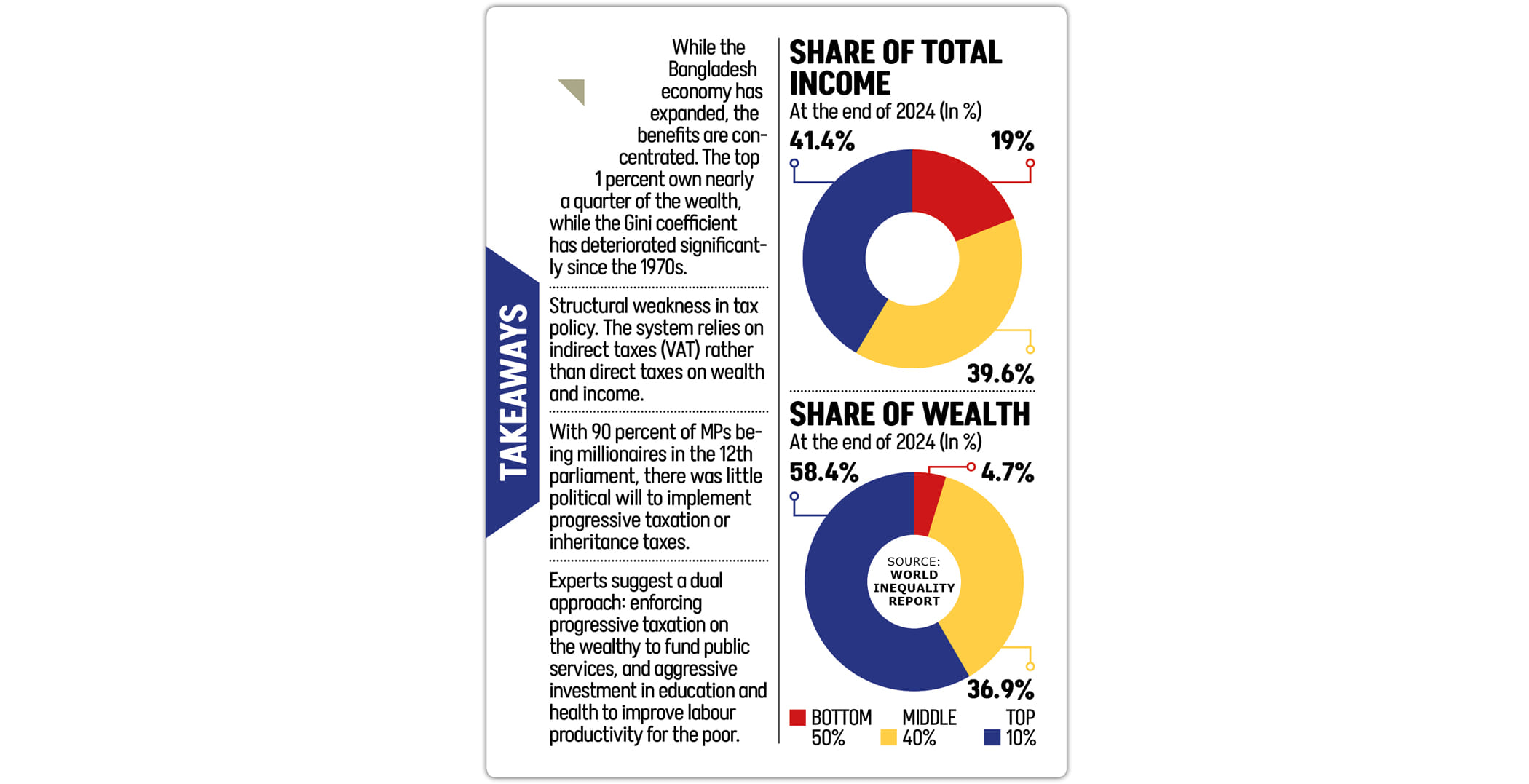

Didar is the face of the bottom 50 percent of Bangladeshis who, despite the country’s economic growth, own a mere 4.7 percent of its wealth.

Yet, a short drive from Didar’s shop, the scenario is starkly different.

In the luxury hotels and marble-floored shopping malls in the capital Dhaka and port city Chattogram, consumption has never been more conspicuous.

Since its independence in 1971, Bangladesh has been a development darling. However, the spoils of this expansion have been hoarded by a heavy-hitting few.

In 1972, the country had five millionaires. By the end of 2024, central bank data showed over 122,000 bank accounts holding more than Tk 1 crore each.

The top 1 percent now hold 24 percent of the total wealth and pocketed 16 percent of the national income in 2024, according to the World Inequality Report.

“Persistent inequality fuels public anger, an anger that has spilled onto the streets in Bangladesh, Nepal and several other countries in recent years and has brought down governments,” says Anu Muhammad, former chairman of the economics department at Jahangirnagar University.

Inequality was at the core of the mass uprising that toppled the Awami League government in 2024.

But he believes that a change of government alone is not enough to solve the problem.

THE GINI CLIMBS, AND STICKS

Simon Kuznets, an economist, famously theorised that inequality follows an inverted “U” shape: it rises as a country develops and industrialises, then falls as the state becomes affluent enough to redistribute.

Bangladesh is stuck on the upward slope. The Gini coefficient, a measure of inequality where 0 is perfect equality and 1 is perfect inequality, has marched steadily upward.

In 1974, the country sat at a Nordic-like 0.36. By 2022, income inequality had hit 0.50, while wealth inequality soared to a staggering 0.84.

The reason for this stickiness is political capture. The mechanism for redistribution -- tax policy -- has been hijacked by those it is meant to tax.

According to Shushashoner Jonno Nagorik (Shujan), a civil-society organisation, 67 percent of lawmakers in the 12th parliament were businessmen; 90 percent were millionaires. This represents a consolidation of power from the previous parliament, where 82 percent were millionaires.

Without a shift in the policy framework, inequality will remain entrenched, says Anu Muhammad, adding that there is still no sign of meaningful change in supporting policies in Bangladesh.

“Tax policy should have been progressive and centred on income tax. Instead, it depends heavily on VAT. At the same time, the social safety net remains shallow, while education and healthcare continue to be costly for people.”

He says, “If black money and laundered funds are included in the accounts, inequality would be much deeper.”

The labour market, he adds, reflects the same imbalance. About 85 percent of jobs come from the informal sector, many without contracts, job security or adequate leave.

A GLOBAL PATTERN, A FAMILIAR FAILURE

Across the globe, living standards for the many are flatlining, even as capital aggregates ever more densely at the top. Inequality is the solvent dissolving the social trust that binds democracies. The arithmetic of this disparity is arresting.

The wealthiest decile of the global population now commands nearly three-quarters of all assets, leaving the bottom half to scrape by with a paltry 2 percent.

A cohort of fewer than 60,000 multi-millionaires controls a fortune triple that of half of humanity combined. In most nations, the poorer half of the population rarely holds more than 5 percent of national wealth, according to the World Inequality Report.

Yet the ultra-rich are making a negligible contribution to the public purse.

The report highlights a regressive anomaly in which effective tax rates, having climbed for the middle classes, drop precipitously for billionaires and centi-millionaires.

This fiscal opting-out does more than offend a sense of fairness; it starves the state of the capital required to fund education, health and the green transition.

In Bangladesh, the tax system remains stubbornly regressive. The country relies heavily on value-added tax (VAT), a consumption tax that hits the poor hardest, rather than income tax.

There is no inheritance tax, a standard tool in the West for preventing dynastic hoarding of wealth. In the 2023-24 budget, the surcharge-free limit on wealth was actually raised to Tk 4 crore from Tk 3 crore, offering further shelter to the rich.

“Those who earn more should be taxed much higher,” argues Mohammad Abdur Razzaque, chairman of Research and Policy Integration for Development (RAPID), a think-tank.

But the state is unable to collect, according to the economist.

He says the revenue collection relative to GDP in Bangladesh is among the lowest in the world. Without that revenue, the government cannot fund the education and skill-upgrading required to make the formal labour market, the surest route out of poverty, accessible to the masses.

THE MISSING REFORM

In terms of inequality, Bangladesh is not an outlier in the South Asian region.

In India, the top 10 percent capture 58 percent of national income; in Pakistan, the figure is 42 percent.

By contrast, the lowest inequality is found in Europe -- Sweden, Norway and France -- where fiscal policy is used aggressively to level the playing field.

Inequality is highest in South Africa, and no improvement has been seen over the past decade.

The top 10 percent of earners capture 66 percent of total income, while the bottom 50 percent receive only 6 percent. Wealth inequality is even more concentrated: the richest 10 percent hold 86 percent of total wealth, and the top 1 percent alone holds 55 percent, while the bottom 50 percent have a negative net wealth of 2.5 percent.

The income gap between the top 10 percent and the bottom 50 percent increased from 103 to 118 between 2014 and 2024.

Mexico, Brazil, Colombia, Chile, Taiwan, and Thailand also have deep inequality problems, with income gaps between the top 10 percent and the bottom 50 percent above 50 percent.

For Bangladesh to change course, it requires a human-capital strategy that equips the poor for better-paying jobs, and a fiscal policy that dares to tax the politically connected.

Until then, the gap will widen. Back in Chattogram, Didar is pouring what little remains of his income into schooling his daughters, hoping they might one day escape the wrong side of the statistics.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments