'Demographic dividend' could turn into a 'demographic disaster'

Bangladesh has a fairly young population with 34 percent aged 15 and younger and just five percent aged 65 and older. At present, more than 65 percent of our population is of working age, between 15 and 64.

When there is such a large percentage of young people in any nation, they are expected to contribute to the country's economy. This opportunity is known as the "demographic dividend" which refers to "the economic growth potential that can result from shifts in a population's age structure, mainly when the share of the working-age population is larger than the non-working-age share of the population," as defined by the United Nations Population Fund.

But reaping the benefits of a demographic dividend is not guaranteed or automatic. It all depends on how much a country invests in key areas like education, health and nutrition, infrastructure, good governance, etc., and whether or not there is an environment suitable for young people so that they are able to contribute to the country's socio-economic growth.

According to analysts, currently Bangladesh is passing through the phase of demographic dividend that emerged in 2007. At present, we are at the midway point of the dividend period. So a good question to ask is, how has this demographic dividend transformed Bangladesh today and how will it transform Bangladesh tomorrow?

Today, Bangladesh is considered one of the fastest growing economies in the world. For the last decade and a half, the country has averaged above six percent annual GDP growth and in the last fiscal year 2017-18, the country recorded the highest ever growth at 7.86 percent. Our per-capita income is USD 1,751 which was only USD 405 in the year 2000. We have also made spectacular progress in different socio-economic sectors, particularly relating to reducing extreme poverty and hunger, promoting gender equality and empowering women, ensuring universal primary education and reducing child mortality. Life expectancy went up to 72 years in 2017 from 65.32 years in 2000.

While we have a long list of achievements to our credit, we have failed on many fronts. We still remain one of the poorest, overpopulated and inefficiently governed countries in the world. The country is still struggling with a huge pool of low-skilled workforce; about 86 percent of the total employed population aged 15 and above are in the informal sector, which is insecure, poorly paid and has no social security, which means that they cannot contribute much to economic development. Almost one in four Bangladeshis (24.3 percent of the population) lives in poverty, 12.9 percent of the population live in extreme poverty, 15.2 percent of the country's population suffer from undernourishment, while 36.1 percent of children under the age of five face growth development issues.

Also, our education system is not yet pro-poor and the curriculum does not serve the goals of human development and poverty eradication. According to a World Bank report, Bangladesh's workforce of 87 million is largely undereducated (only four percent of workers have higher than secondary education), and the overall quality of the country's human capital is low. An internal report of the Directorate of Primary Education (DPE) of 2015 states that around 70 percent of children are unable to read or write properly, or perform basic mathematical calculations even after five years at primary school and most of those who graduate from primary schools do not acquire the nationally defined basic competence. While the enrolment rate is appreciably high at primary level, a large proportion of them don't make it to secondary schools (11-15 years). The government's own statistics from the Bangladesh Bureau of Educational Information and Statistics (BANBEIS) show that in 2015, the national dropout rate at the secondary level was 40.29 percent, out of which 45.92 percent were girls and 33.72 percent were boys. And currently, there are about four million children in the age group of 6-10 who are out of school in Bangladesh.

The economic growth that our leaders often boast about has actually bypassed the major portion of the population while higher-income groups have been the main beneficiaries. A report titled "Household Income and Expenditure Survey (HIES) 2016," published by the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS), shows that the rich-poor gap in terms of wealth accumulation has been widening in the country. The poorest five percent had 0.78 percent of the national income in their possession back in 2010, and now their share is only 0.23 percent. By contrast, the richest five percent, who had 24.61 percent of the national income in 2010, now have a higher share—27.89 percent to be precise. In other words, the bottom five percent's share of national income has decreased, whereas the richest five percent's has increased.

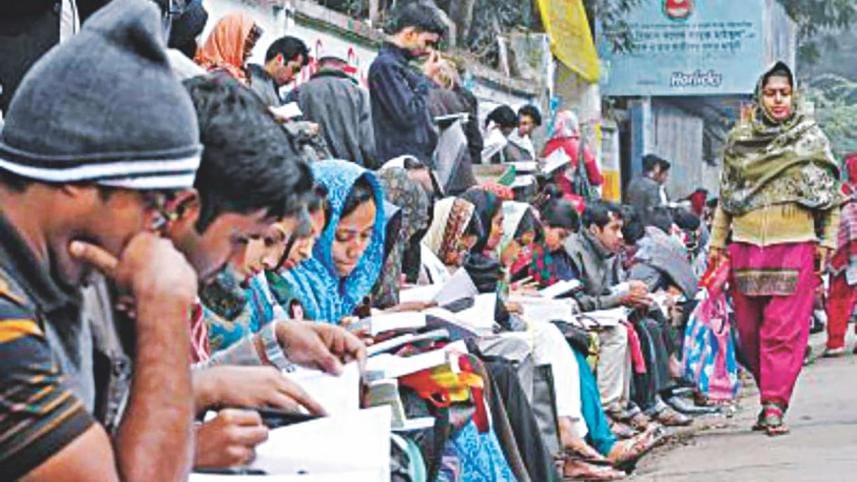

Moreover, the economic growth has also failed to create enough jobs for the millions of young Bangladeshis joining the workforce every year. Different studies show that between 2013 and 2017, while the average annual GDP growth was 6.6 percent, the average annual growth of jobs was only 0.9 percent. The employment share of the manufacturing sector actually declined from 16.4 percent to 14.4 percent. This is in addition to a decline in manufacturing jobs of 0.77 million and female employment of 0.92 million (Bangladesh Labour Force Survey cited by SANEM, 2018). The slow growth in job creation is also reflected in the declining employment elasticity over the last decade. The overall employment elasticity with respect to GDP growth declined from 0.54 during 1995-2000 to 0.25 in 2010-2018. What is worrying is that the share of the youth population not in education, economic activities and training (NEET) increased from 25.4 percent in 2013 to 29.8 percent in 2016-17—more than one-fourth of all young people are not participating in any form of economic or educational activities.

Our policymakers need to realise that for a country where 24.3 percent of the population live below the national poverty line, no matter what the GDP growth rate or per-capita income is, rising income inequality and millions of young people unemployed or underemployed point to a ticking time bomb. Moreover, our population will reach 223.5 million by 2041 and 230-240 million by 2050. As mentioned earlier, this demographic dividend is not guaranteed or automatic—dividend comes of use when jobs are created, and when young people join the workforce. Therefore, if we want to reap the full benefits of the demographic dividend, we need to act fast because demographic dividend is a one-time short-lived phenomenon that usually continues for 30 to 35 years, and by 2045 to 2060, this window of opportunity to accelerate economic growth will start to disappear.

So before time runs out, we must act to prepare our young people for the future world of work. Since most new jobs that will be created in the future will be highly skilled, we need to revamp our weak education system to make it more suitable to the changing times. Alongside that, we must invest much more in education, health and nutrition, infrastructure, and adopt an expansionary economic policy and create a favourable environment for local and foreign investment, so that we can increase production, productivity and consequent employment opportunities for the future workforce. If we succeed, we will ensure the prosperity of our people. And if we fail, our "demographic dividend" can turn into a "demographic disaster."

Abu Afsarul Haider studied economics and business administration at the Illinois State University, USA, and is currently involved in international trade in Dhaka. Email: afsarulhaider@gmail.com

Comments