Alhambra: Europe’s love letter to Moorish culture

For centuries, the Muslims have ruled large swaths of an unconverted population in Spain, the Balkans, and India. Each of these countries has endured periodic cycles of religious violence and ethnic cleansing of the Muslims — Balkans in the 1990s and the bitter partition of India in 1947. There are still Muslims in the Balkans. And despite partition, which saw the creation of a predominantly Muslim Pakistan, there are still around 210 million Muslims in India.

What makes Spain unique is that here ethnic cleansing was fully realised. Yet, everywhere in the Andalusian part of Spain my wife and I went recently, we were surrounded by the remains of the Moors, who are Muslims from North Africa. This was particularly so in Granada, which is all about the Alhambra, "Europe's love letter to Moorish culture".

An exquisite ensemble of Islamic architecture and art, celebrated for centuries in poetry and songs, its image endlessly replicated on postcards, the Alhambra represents the essence of Andalusia. As the last and greatest Moorish palace and one of the world's finest architectural wonders of the Islamic Golden Age in Europe, it is a historic landmark encrusted with romantic associations.

The Alhambra — al-qal'a al-hamra in Arabic, meaning red fort or castle — is more than just a palace. Named for the reddish walls and towers that surround the citadel, it is a walled city within the city of Granada.

Perched on top of the Sabika Hill and set against the majestic mountain range of Sierra Nevada, the impressive palace was built between the 13th and 14th centuries by the Moorish monarch Ibn al-Ahmar and his successors of the Nasrid Dynasty, one of the longest-ruling Muslim dynasties in Spain.

After reigning for more than 250 years, Moorish rule was on the decline and eventually ended in 1492 with the Christian Reconquista of Granada. However, unlike the conquerors who ripped apart every semblance of other cultures elsewhere, Catholic Monarchs Queen Isabella of Castile and King Ferdinand of Aragon walked into Alhambra and probably thought, not this one.

The palace is beautifully laid out in three sections: The Mexuar where matters concerning the administration of justice were dealt with, Palace of Ceremonial Rooms — a throne room where the rulers of Granada received foreign envoys, and the Palace of the Lions — the Sultan's private quarters.

We took a guided tour because it is impossible to go through the complex on one's own. Walking through the rooms of the palace was a progressive experience that became more and more marvellous. Exotic Middle Eastern tiles, stucco decorations, and delicate carvings on the walls of the lavishly decorated rooms and serene courtyards speak loudly of the finest achievements of Moorish art and architecture in the world. While the rooms are empty, it takes a little bit of imagination to picture the ornate furnishings that filled the vast rooms when the Moors ruled Spain.

Carved wood, intricate plaster arches, decorative columns, and elegantly laid mosaics define the Alhambra. Islamic calligraphy, mostly poems, floral patterns and verses from the Quran etched on mosaic could be seen everywhere. The phrases "Allah hu Akbar" and "La Ilaha Illa Allah" are repeated thousands of times throughout the palace.

There is a hall with a dome displaying in great detail a dazzling honeycomb that appears to drip like icicles in a cave. It is called the "Hall of the Two Sisters" because of the two large identical slabs of marble on the floor. The walls of the hall are covered with extremely fine plasterwork with different themes, among which is Kalima Tayyab: "There is no god but God but Allah, and Muhammad is His messenger."

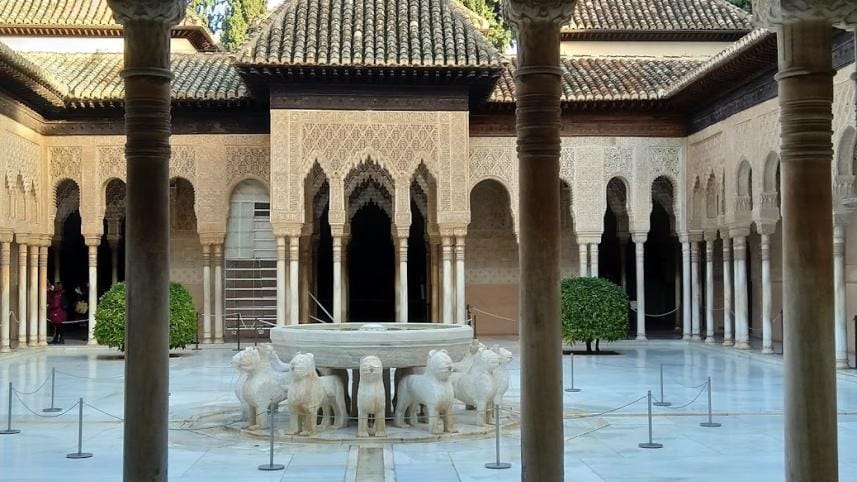

An alluring structure in the Alhambra complex is the Courtyard of the Lions. It has a central alabaster fountain encircled by twelve white marble lions spewing jets of water. The courtyard was a private area for the king, his family, and mistresses. Encompassing the courtyard is an ornately decorated gallery supported by white marble columns. There is a pavilion with filigree walls and a wooden domed ceiling, projecting into the courtyard at each extremity.

At the east end of the Courtyard of Lions is the Hall of Justice where 15th century ceiling paintings are wonderfully preserved its alcove-like recesses. Most noteworthy are three paintings on leather depicting scenes of court life with portraits of rulers and councillors, a hunting scene, and rescue of a maiden from the clutches of a wild man.

Another section of the palace that impressed us beyond measure is a spacious courtyard called Patio del Mexuar. It features graceful arcades and two fountains, feeding a pond. The green water of the pond contrasts brilliantly with the white marble patio and the parapet above the northern gallery that reflects in the pool on a clear day. It is also called the Courtyard of the Myrtles. The myrtle bushes that surround the central pond and their bright green colour pleasingly accentuate the whiteness of the surrounding stone.

We eventually emerged into an area of terraced gardens called Jardines de Partal. Here a reflecting pool stands in front of the Palacio del Partal, a small portico-style building with its own tower.

From the Partal gardens, we continued along a path to the Generalife, our last stop at Alhambra. Taking its name from the Arabic phrase jinan al-'arif, meaning "Garden of the overseer," Generalife is a terraced garden, situated on the slopes of Cerro del Sol, which is Spanish for Hill of the Sun. Pools, patios, trickling fountains, maze-like hedges along with exotic flowers, fragrant orange trees, cypresses, roses and a soothing ensemble of pathways combine to form an enchanting effect at Generalife. Simply stated, the garden is stunning, something that looks like out of a fairy tale.

In sum, the graceful, reticent decoration and inlay of the Alhambra give the eye a sense of lightness. In the words of a European visitor, Alhambra is "so magnificent, so exquisitely executed that even he who contemplates it can scarcely be sure that he is not in a paradise."

The writer is a Professor of Physics at Fordham University, New York, USA.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments