[WATCH] Amazing facts about the immortal cells of Henrietta Lacks

The story of Henrietta Lacks, a poor, black tobacco farmer from southern Virginia, is as astounding as it is miraculous. She was diagnosed with a type of extremely aggressive cervical. Scientists had long been trying to cultivate human tissue in the lab without success. After Henrietta's tumor was biopsied, they finally got the answer, and the events that followed created a ripple effect so great that the world of medicine was never the same.

Here are some amazing facts that Listverse.com reports about the immortal cells of Henrietta Lacks.

Henrietta's tumor produced the first immortal human cells grown in culture

In January 1951, Henrietta was admitted to Johns Hopkins Gynecology Clinic after she began bleeding profusely. She received her cervical cancer diagnosis, had a small sample taken of her tumor, and was given radiation and surgical treatment. Unfortunately, Henrietta's cancer spread so quickly that nothing could be done to save her. She died in October the same year.

Henrietta's tissue sample was sent to Dr George Otto Gey, the head of tissue culture research at Johns Hopkins. For years, Gey had been trying to produce a line of cells that could live eternally in a laboratory environment. Finally, he succeeded by using his own cultivation technique, which involved preserving the cells in a fluid of chicken plasma, beef embryo extract, and human placental cord serum. Upon observation, Gey discovered that Henrietta's cells were rapidly and continuously multiplying. In less than two years, Henrietta's tissue samples were packaged carefully and distributed all around the world. The cells were called "HeLa" cells after the first two letters of Henrietta's first and last names.

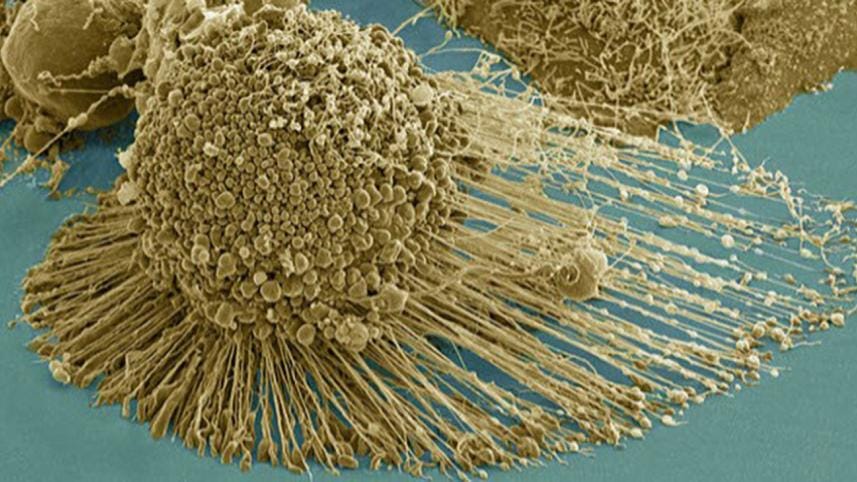

It is amazing that the number of HeLa cells grown to date spans more than 105 kilometers (65 miles), and are capable of wrapping around the Earth's equator more than three times. Moreover, despite being cancerous, HeLa cells behaved like normal cells in the body, allowing scientists to learn how they reacted in certain environments. Research possibilities that were once off-limits or unethical suddenly became a reality as scientists started to understand how cell division occurred or how a virus affected a cell. Henrietta's tragic end brought the dawn of a remarkable future in science and medicine.

The cells were taken without her knowledge or consent

Back in the 1950s, it was not considered unethical to use someone in a scientific study without his permission or to provide unauthorized medical treatment. There were no laws to protect the rights of people like Henrietta who had their privacy violated by researchers. Dr Gey initially attributed the scientific miracle to an imagined woman named "Helen Lane" in attempt to conceal Henrietta's true identity. It was many years later that the truth came to light. Although Henrietta did not receive the recognition that she rightly deserved at the time, Gey seemingly had the right intentions. He is said to have devoted his life to culture research, going so far as to use his family and himself for his studies. His only hope for the cells was that they would have the scientific impact that they actually did at the time. Although Gey had financial struggles of his own, he never sold any of Henrietta's tissue samples. However, many companies and industries made profits from Gey's HeLa cells in future.

A medical mystery

Why Henrietta's cancer cells replicated so quickly and aggressively without dying baffled the scientists for years. According to some, it may have been a combination of human papillomavirus (HPV) and Henrietta's DNA that caused the cells to behave as they did. Furthermore, it was found that she had syphilis, which resulted in an aggressive growth of cancer cells due to a weakened immune system.

However, a highly probable answer surfaced in 2013. According to a study by University of Washington researchers, the scrambled HPV genome (which contains cancer genes of its own) inserted itself near an oncogene (a gene that can cause cancer when altered) in Henrietta's genome. This activated the oncogene and caused the rapid replication of HeLa cells in Henrietta's body.

"This was in a sense a perfect storm of what can go wrong in a cell," said Andrew Adey, one of the study's authors, adding that "The HPV virus inserted into her genome in what might be the worst possible way."

The Lack family was kept in the dark about HeLa cells

Despite the fact that Henrietta's cells helped to save millions of lives, neither she nor her family benefited from it. Initially, her family had no idea that her cells were used in the groundbreaking accomplishment. When Bobette Lacks, Henrietta's daughter-in-law, coincidentally met a cancer researcher years later, Bobette learned that Henrietta's cells had been growing since her death in 1951. Sadly, the treatments that were developed using HeLa cells were out of reach for the Lacks. Like many others without insurance, the Lacks could not afford them. Henrietta's husband had prostate cancer, their eldest daughter had developmental issues, and another daughter had a host of medical issues that they were unable to treat. The family that should have been compensated simply was not.

In an unexpected twist of fate, the Lacks family finally received some reparation in 2013 for their matriarch's contribution. A research team at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory had sequenced and published Henrietta's genome without the consent of her family. Upon hearing about the publication, Henrietta's grandchildren felt as though this further research would violate their family's private medical history. They took a stand and requested that the scientists retract their study. The family eventually agreed to allow the publication of much of the information about Henrietta's genome.

HeLa cells were instrumental in early cancer research

Studying the HeLa cells, researchers have learned a lot about the operation of cancer cells. It was discovered that Henrietta's cancerous cells activated an enzyme called telomerase that the cells used to repair damaged DNA. This meant that HeLa cells proliferated and thrived as opposed to regular cells that simply died after a short time. Scientists also learned that telomerase encouraged elongation of the chromosomes. In normal human cell division, telomeres (the tips of the chromosomes) become shorter after each division. After a while, the cells are destroyed because the telomeres can no longer shorten. In HeLa cells, however, this process is a little different. As telomerase is hyperactive in HeLa cells, the telomeres never become depleted. The resulting continuous division of cancer cells has made the cell line vitally important for cancer studies—even today. These discoveries have led to further research that has brought about advancements in cancer treatments.

HeLa cells aided the progression of genetic research

In 1953, a Texas geneticist was working with HeLa cells when a chemical accidentally spilled on them. However, this potential disaster turned out to be a blessing in disguise. The scientist noticed that the chromosomes within the cells increased in size and essentially untangled themselves, making them more visible. Two years later, Joe Hin Tjio and Albert Levan developed an improved technique that led to the discovery that normal human cells definitely have only 46 chromosomes. Before this breakthrough was made, it had been incredibly difficult to count the chromosomes due to the small size and compact structure of DNA. Furthermore, it had been widely accepted that humans had 48 chromosomes—like chimpanzees and gorillas. This finding was monumental because it allowed the diagnosis of genetic diseases when someone's cells were found to have more or fewer than 46 chromosomes.

Research using HeLa cells led to the creation of the cervical cancer vaccination

In 2008, German virologist Harald zur Hausen was awarded the Nobel Prize for his milestone discovery that two strains of HPV were directly linked to cervical cancer. In the 1970s, it was believed that herpes simplex caused cervical cancer. But zur Hausen, who worked with the HeLa cell line, found that the genes of certain strains of the virus, including HPV16 and HPV18, maneuvered themselves inside the cells of the cervix and caused abnormal cell replication.

Years before zur Hausen's success, scientists had been working toward an HPV vaccine that would prevent the virus and reduce the risk of cervical cancer among women. During the 1990s, scientists affiliated with the National Cancer Institute identified certain proteins on the outside of the virus that were similar to the virus itself. This was a major development because the proteins were found to stimulate the growth of antibodies. All of this research led to the formulation of Gardasil and Cervarix, two HPV vaccines that are on the market today.

HeLa cells contaminated other cell cultures worldwide

In 1966, geneticist Stanley Gartler noticed something odd while working with sample tissues. All of the cells contained an enzyme called glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase-A (G6PD-A). Gartler was puzzled because he knew that the tissue samples were taken from Caucasians and even animals. G6PD-A is an enzyme that is only found in humans and almost exclusively in African Americans. This was troubling because it meant that Gartler's samples, as well as many others, were contaminated. Gartler theorized that the culprit was the HeLa cell line. After initial doubts from other scientists—who feared the potential loss of millions of dollars—Gartler's suspicions were confirmed. Proper care had not been taken to prevent samples from becoming contaminated as they were transferred between laboratories. Millions of dollars of research were ruined in the process. It was also discovered that HeLa cells could travel through the air. At that time, laboratories were not properly equipped to stop it. Fortunately, improvements to inhibit such errors have been made to cell culture techniques since then.

HeLa cells helped to create the Polio vaccine

Jonas Salk was a researcher at the University of Pittsburgh whose years of work led to the end of the polio epidemic that swept through the US in the 1950s. Before Salk's polio vaccine could be completed, however, he needed massive quantities of tissue samples for his work. Luckily, the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis was willing to fund a facility at Tuskegee Institute that was specifically geared toward the production of HeLa cells. Once equipped with the cancer cells, Salk was able to carry out testing on a large scale. On April 26, 1954, tests began on nearly two million American, Finnish, and Canadian children. When the results came back, it was found that the vaccine was safe and effective. Since then, the vaccine has become a staple of child healthcare around the world.

Scientists suggest HeLa cells may be a new species

According to evolutionary biologist Leigh Van Valen of the University of Chicago, HeLa cells have no connection to people. Van Valen and other scientists claim that the cells are microbial in nature, bear no resemblance to human cells, and should be considered as an entirely new species. It is believed that HeLa cells have genetically evolved over time to adapt to their environment—the petri dish—as a result of natural selection.

It has been reported that there are now new strains of HeLa cells that have arisen in recent years. Another study suggests that the process of cancer cell generation is the basis for the creation of a new species. It also makes mention of tumors that should be thought of as "parasitic organisms." Researchers have now proposed a new scientific name for HeLa cells—Helacyton gartleri—after Stanley Gartler who recognized how successful HeLa cells actually were.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments