Blood, sweat, tears

"…Then after dark, a tentative 'Joy Bangla' in the back streets. Older men came out and persuaded the lads back into their homes; 'there is still a curfew'. Then a more determined 'Joy Bangla'. The Mukti Bahini had taken over the streets. They tried to keep the shouting to the back streets. But they could not do it for long, and soon all the city was ringing with it. 'Joy Bangla!'..."

This is how Bishop James D Blair captured the nerve-racking moments leading to the Pakistan army's surrender to the joint command of Bangladesh and Indian forces on December 16, 1971.

The description appears in a six-page newsletter by the Bishop of Dhaka Diocese of the then Church of Pakistan for the Anglican Christians of East Bengal. It was penned between December 1971 and January 1972, and a copy was sent to the UK.

Forty-seven years later, the newsletter came back in the form of an email to the land it originated from with eyewitness accounts of the most crucial period in Bangladesh's history.

Written in a personal manner, the newsletter described Bishop's attempts to visit different churches under his diocese (an area under a bishop) immediately after December 16. He also summarised the news he received from different parts of the country during the war.

In the very first para, he mentioned the horrific slaughter carried out by the Al Badr, referred to as "the fanatic types of Bengali [Bangalee] Muslims", and the armed Biharis, the Urdu-speaking people.

According to historic documents, infamous Al-Badr Bahini was formed with selected members of Islami Chhatra Sangha, the then student wing of anti-liberation party Jamaat-e-Islami, and played a key role in the wholesale murder of intellectuals on the eve of the victory on December 16, 1971.

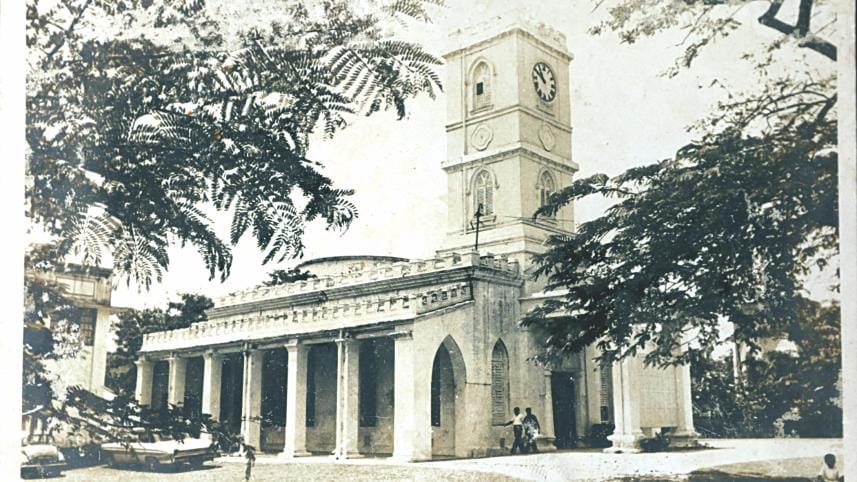

"The tale of slaughter is big enough as it is, with the dead set at the intellectuals, and for some reason the doctors as well, together with plenty of ordinary Bengalis…." wrote Bishop Blair, then posted at St Thomas Cathedral, which had come under mortar shell attacks on the night of March 25.

A whole paragraph describes his concern about the reactions of the armed Biharis following the Pakistan army's surrender.

"…among the Biharis there were two types; one which would have accepted the situation and lived in peace with their Bengali neighbours, and the other which in the last days of the military regime were saying openly in the bazaar, 'Let us kill as many Bengalis [Banglalees] as we can while we can'."

He narrated an incident when a riot broke out in Nawabpur in the last days before victory, between Biharis and Bangalees, which was later quelled by the freedom fighters and Biharis who were "saner".

On fears about reprisals, he wrote: "There is hardly a family in Bengal who is not mourning the loss of some relations and the loss of money or property. A complete amnesty would be psychologically impossible."

About the government steps in post-war Bangladesh, he wrote: "The government has announced that no one is to be punished without trial, and therefore no-one is to take the law into his own hands. This is the best that they can hope to do. Unless they promised punishment after trial, people would certainly take the law into their own hands."

He drew a vivid picture of the war-torn country, broken communication system, casualties of the Christian communities and missionaries, and the curfews towardsthe end of the war.

'LITTLE TO LOSE, ALL TO GAIN'

He described the night of December 3, right before Indian fighter jets started bombing Pakistani military establishments in Dhaka.

The Bishop had gone for supper in Dhanmondi. The dean of St Thomas Cathedral, Father Simon Delves Broughton, and his wife Marcia Delves Broughton were also out in Gulshan.

On his way back to the church, on Johnson Road in Old Dhaka, he found that the streets were quiet and dark; curfew was imposed and there was a blackout.

"So, I had to stay where I was. Simon made his way home in ignorance through the curfew. At 2:30am or so the fun began; sirens and then fireworks over the airport about a mile away from where I was. We did not get much more sleep that night."

Father Simon and Marcia still remember that night. Talking to The Daily Star over phone from the UK, the couple shared how the streets were full of soldiers but somehow, they managed to get back to the church safe and sound.

Blair's thoughtful insights is reflected in the para where he wrote about the broken morale of the Pakistan army.

"When you let an army loose to loot and plunder and murder and rape, and when for nine months their fighting has been against unarmed civilians, and only occasionally against the elusive Mukti Bahini, you cannot preserve their morale. I had felt sure all along that when it came to the test, they would find they had forgotten how to fight. All they wanted to do was to get home and enjoy their ill-gotten gains."

On the other hand, he lauded the courage of the members of Mukti Bahini. "Some had ten days training, some a month. They were taught how to use their weapons and the rest was left to their native wit. Desperate lads most of them who had little to lose and all to gain."

Talking about the last part of the Liberation War, he wrote "They [the freedom fighters] knew every move of the Pak soldiers. They knew exactly where Niazi was lurking; and they got the news through with surprising speed. The Pak army did not stand a chance. I wonder if Yahya has ever read a history book in his life. He behaved as if he hadn't."

In recognition to the newly independent Bangladesh, in the very last paragraph of the letter, he wrote, "We obviously cannot now be the Church of Pakistan, as this is no longer Pakistan. We shall let the dust settle and then we shall see. Temporarily we call ourselves the Church of Bangladesh, as we have to call ourselves something."

Father Simon D Broughton told The Daily Star that they even hoisted the Bangladeshi flag on the church compound when the war ended.

Bishop Blair's hope for the new country is reflected in the second last para, where he observed ardently:

"The future has terrible problems, and there are all sorts of possibilities. But there always have been in this country. Life is never dull. But now they have won their independence; although they had valuable help in the end, the Bengalis have spent quite enough blood, sweat and tears. They can truly feel that the victory is theirs. It has not been handed to them on a plate. There is a healthy determination to make their country a better one, and one where the poor are less poor and the rich less rich, and where corruption does not frustrate every effort to improve. Good luck to them, and may God bless them."

HOW WE CAME ACROSS THE NEWSLETTER?

The Scottish-Indian Bishop was a priest of Kolkata-based Oxford Mission. He was born in 1906 in India's Roorkee, where his parents worked as missionaries.

Until 1951 the Anglican Church in East Pakistan was under the Diocese of Calcutta. After 1952, Dhaka became a Diocese of the Church of North India, Pakistan, Burma and Ceylon, and Blair was consecrated as the first Bishop of Dhaka Diocese, according to the website of Church of Bangladesh.

Various documents show that he served in this position till 1975, when he returned to Kolkata where he died in 1991 at the age of 85. He lived in different districts of Bangladesh for about five decades.

According to Oxford Mission's website, during his term as a bishop, Blair wrote and sent out a lively and informal diocesan newsletter every few months.

A copy was sent out to his friend George Davey, who was the deputy high commissioner of the United Kingdom posted in the erstwhile East Pakistan between 1955 and 1958.

Davey's daughter Susan Moulds, who lives in Buckinghamshire in England in the UK, discovered the newsletter eight years ago, after her mother's death.

"My mother passed away in 2000 and left a lot of papers and documents. Recently, as my siblings and I went through the papers, we came across the newsletter," she narrated over phone.

She told The Daily Star that she was in the then East Pakistan with her parents as a child and remembers Bishop Blair as a family friend. Her mother had kept in touch with Bishop Blair even after they left Dhaka in 1959.

Susan shared her discovery with her friend Dr David Sherlock, an orthopaedic surgeon in Scotland, who in turn sent a copy of the newsletter to Dr Md Wahidur Rahman, a physician friend in Dhaka.

Dr Wahid forwarded it to a friend who works at The Daily Star.

[Read the full newsletter]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments